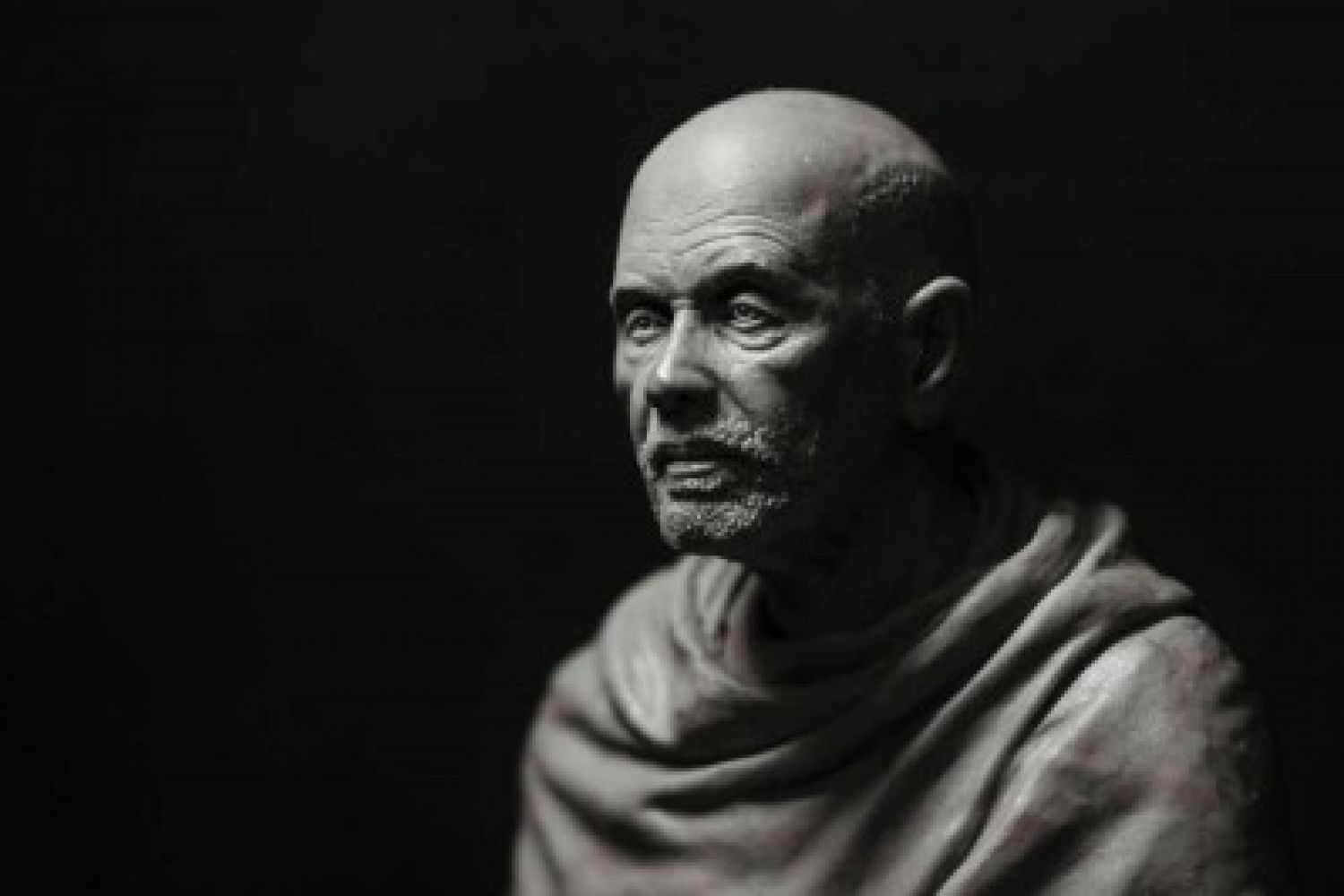

Letter to the Little

Devil, 1921.

Guru was living in

Shivagiri. One day two people came to meet him. Guru enquired about the purpose

of their visit and they said: We came searching for help. Only you can help us.

Guru: Help from me?

Please narrate.

My house has been

haunted by a Little Devil for a long time now. We cannot sleep peacefully. We

tried many things but nothing has changed. Please save us.

Guru: Who? Little

Devil? That is nice. Did anyone see him?

Yes. We saw him

Continue reading “Narayana Guru and the Little Devil”

Read this story with a subscription.