When tragedy falls on the forest, it falls on us. I feel a lot of pain seeing how our beautiful jungle has been destroyed this way.

—Achchugegowda, 65, Soliga tribal elder.

It takes a while amid the shades of

green that cover a forest to spot lantana, the small woody shrub that has

colonised the Western Ghats. Once seen, it appears everywhere. It engulfs the

floor of the forest, in violet, red, pink, orange, and yellow and rises into

dense thickets. A single plant can have several looping outgrowths, tentacles

that twine themselves around branches and trees, sometimes reaching as high as

20 metres and forming a canopy. Slowly choking the trees and hogging nutrients

in the soil, this ornamental-plant-turned-weed can change a forest

forever.

Inside Karnataka’s Biligiri Ranganatha Temple Tiger Reserve (BRT) in the southern Western Ghats, the lantana is so dense that the understorey—plant life below the canopy—is almost completely swallowed by it. Worse, it blocks sunlight, allowing no other plant to survive. Even animals find it difficult to pass through the thicker patches.

The Erikkenagaddupodu (forest village) is home to Achchugegowda, a member of the Soliga tribe. They are a Scheduled Tribe numbering around 21,000, who worship the forests in and around the BRT hills. One of their principal deities, the Doddasampige, is a 600-year-old gigantic champaka tree that resembles Lord Shiva with a braid.

I started going deep into the forest with my parents when I was six. They trained me to collect leaves, roots, fruits and honey for food. What a beautiful forest it was! What a beautiful forest! We had thousands of species of plants, and hundreds of varieties of grass; I can’t even put a number to how many we had.

Before 1973, the year the forest was declared a wildlife sanctuary, Achchugegowda practised shifting cultivation—burning a patch of forest and cultivating for three years before shifting to another part.

He remembers BRT before lantana: “I started going deep into the forest with my parents when I was six. They trained me to collect leaves, roots, fruits and honey for food. What a beautiful forest it was! What a beautiful forest! We had thousands of species of plants, and hundreds of varieties of grass; I can’t even put a number to how many we had.” He talks about 1,000-year old trees, amla (gooseberry) trees that yielded more than 50 kg of fruit, and the tigers, bears, and elephants that he’d come across.

“It used to rain the whole of January and at least half of February. On many days, we had 24 hours of rain.” This was also when the Soligas practised “tharagubenki” (litter fire/ controlled burning), which would spur new growth in the forest.

“The whole forest would look so beautiful... flowers would bloom, new grass would sprout, mango and gooseberry trees would bear fruit. The forest would be full of fragrance,” he says. “In those days, we used to see just one or two lantana plants on the roadside, and that too in parts where we did not cultivate.”

Puttarangegowda, another resident who is a couple of decades younger than Achchugegowda, recalled that even as late as 1976, when his family moved out of the forest, it had all kinds of produce—amla, Indian Kino, teak, matti (Indian laurel), tendu (beedi leaf), and mango. “There was some lantana, we used to eat the fruits when we were young.” But now the forest belongs to lantana.

“There is no grass anymore, and animals that grazed there have migrated to the scrubland downhill. They get drawn to the fields of sugarcane and banana right next to the scrubland. They go there and get killed,” he says.

“All because of lantana.”

***

Lantana camara occupies millions of hectares in three continents

outside its native habitat, Brazil. Introduced by explorer-colonisers as an

ornamental plant in tropical parts of Africa, Asia, and Australia in the 19th

century, it is now identified among the top ten invasive species in the world

by the Global Invasive Species Information Network, making it one of the most

dangerous plants in history. In something of a parallel to its planters,

lantana has spread with such ferocity as to push out and threaten the native

species of the region. In India, lantana is estimated to occupy around 13

million hectares, about the size of Tamil Nadu; in Australia, over five million

hectares; and in South Africa, two million hectares. Its removal is not easy.

Lantana camara occupies millions of hectares in three continents outside its native habitat, Brazil. Introduced by explorer-colonisers as an ornamental plant in tropical parts of Africa, Asia, and Australia in the 19th century, it is now identified among the top ten invasive species in the world by the Global Invasive Species Information Network, making it one of the most dangerous plants in history.

As far back as 1973, Australia was

spending $1 million a year to control lantana. South Africa was spending

$250,000 a year in 1999. Their efforts extended to legislation. Both Australia

and South Africa prohibit sale of lantana; owners have to eradicate lantana on

their property.

In India, the prospects are frightening. Using ecological niche modelling, a method to predict the future spread of an invasive species in a particular habitat, scientists have estimated that India is more at peril from an invasion by lantana than any other region.

Lantana taking over a patch of the BRT Hills Tiger Reserve in Karnataka. Photo: Shamsheer Yousaf

Lantana taking over a patch of the BRT Hills Tiger Reserve in Karnataka. Photo: Shamsheer Yousaf“Indeed, so broad is lantana’s distribution in India that its environmental niche is broader there than elsewhere in the world, suggesting that solutions that are likely to work elsewhere may not be applicable across all sites in India”, said Geetha Ramaswami in her 2016 paper on how birds aid in the invasion of lantana. The University of Delhi estimated in 2009 that mechanical extraction would cost ₹9,000 per hectare. At current rates of conversion, it would cost more than $1.7 billion to remove the lantana. It is found in all types of ecosystems: Tropical evergreen forest, tropical moist-deciduous forest, dry deciduous forest, scrub forest, and subtropical moist-deciduous.

Several protected areas are infested by this predator—BRT, Bandipur National Park, Corbett Tiger Reserve, Rajaji National Park, Kalakad Mundanturai Tiger Reserve, Greater Nicobar Biosphere Reserve, Achanakmar-Amarkantak Biosphere Reserve, Mudumalai National Park, Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Melghat Tiger Reserve, Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve. In large parts of the Western Ghats, lantana comprises up to three-quarters of the understorey mass. That number is rapidly increasing.

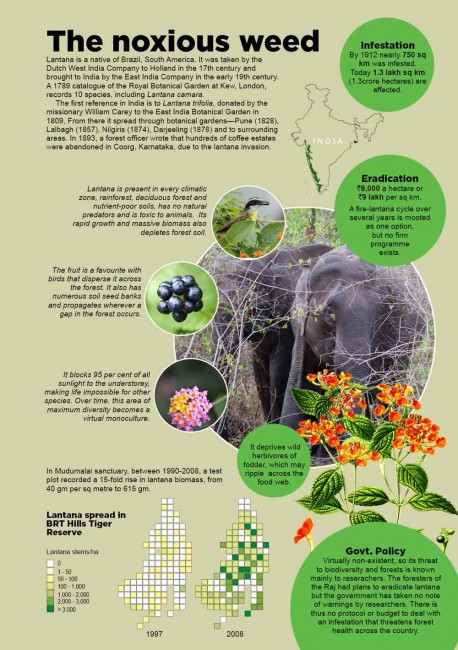

In Mudumalai, a 2013 study by Geetha Ramaswami and Raman Sukumar showed a tremendous explosion between 1990 and 2008. In a 50-hectare observation plot, part of a large network of worldwide permanent plots, the authors found that total lantana biomass increased by 15 times—from 40 gram per square metre in 1990 to 615 in 2008. Moreover, in 1990, only two per cent of the plots had a “dense” infestation. By 2008, it had risen to 18 per cent, indicating a “rapid intensification of invasion”.

Nothing, it appears, can kill the plant; in fact, the regular killers seem to nurture it—between 2002 and 2004, there were two severe droughts in the region, but lantana density exploded fourfold in this period.

In neighbouring BRT, a study by Ankila J. Hiremath and Bharath Sundaram between 1997 and 2008 found that lantana occurrence doubled from 40 per cent to 80 per cent across 540 sq. km of the reserve in that period; moreover, density proportion of lantana to native vegetation increased sevenfold, from one in every 20 stems in 1997 to one in every three by 2008.

The understorey is the loser—non-woody plants like grasses, forbs, and ferns. Geetha Ramaswami, a research associate at the Nature Conservation Foundation, and someone who has been working on lantana for the last decade, says: “If you go under lantana and measure how much light is coming there, it’s like 10 per cent less than what’s available outside. In the forest it is about 70 to 80 per cent shade, while under lantana you get as much as 95 per cent shade. Species that cannot tolerate 95 per cent shade would surely be affected.”

The understorey hosts some of the largest diversity of plant species in a forest; though it constitutes less than one per cent of the biomass, it contains 90 per cent of the plant species. It also contributes litter to the forest floor, which provides nutrition to the soil.

The biggest impact of lantana is on native varieties of grass. Ayesha E. Prasad, in a 2008 report for the Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore, on the impact of lantana on wildlife habitat in Bandipur Tiger Reserve, notes: “Lantana renders large amounts of forage inaccessible to wild herbivores, which are prey for large carnivores like the tiger. Thus it may have food-web level impacts and decrease the suitability of this habitat for wildlife.”

Elephants, deer, bears, and tigers are being pushed out of the forests in search of food.

***

The story of lantana’s romp across

the world is a study in human error. The plant of the lantana genus was first

identified and recorded by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, father of modern

taxonomy. The culprit who took lantana outside its original habitat is

Geoctroyeerde Westindische Compaigne—better known as the Dutch West India

Company. It frequently transported plants—edible and ornamental—from Central

and South America to Europe which then found their way into botanical gardens

across the continent.

Dutch explorers in Brazil are believed to have brought back the plant to their home country in the 17th century. A 1789 catalogue of the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew recorded 10 species, including Lantana camara which was introduced in London between 1690 and 1770. Archival information indicates that they were transported to European colonies in the 19th and 20th centuries.

In 2012, Ramesh Kannan (a young researcher who died a year later at the age of 37) from the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), with Charlie M. Shackleton, and R. Uma Shanker published a paper seeking to reconstruct the plant’s history in India.

The paper dug into archival records on plant imports by the British East India Company. They studied the Imperial Gazetteers of India, books on Indian flora published by pioneer botanists, and letters between colonial officials stationed in Europe and India to follow its trail across the Raj.

The researchers studied herbarium records of lantana lodged between 1814 and 2000 from the four largest and old herbaria in India—Howrah, Pune, Dehradun, and Coimbatore. They also gathered data from a survey answered by 73 retired forest officials who worked in the Western Ghats between 1950 and 2000.

It turned out that the botanical gardens were largely to blame. The East India Botanical Garden of Calcutta, established in 1786, had introduced nearly 1,000 species from outside India within 30 years, including some from Central and South America. The British believed they would prove beneficial for both agriculture and horticulture. For the latter, flowering plants were particularly desired.

An example of the diligence behind this endeavour can be seen in the questionnaires the East India Company’s Secretary of Agricultural and Horticultural Society Dr. Henry Harpur Spry sent to various officers across India. They would gather information on soil, precipitation, and plant species in the region, and also sought recommendations for the introduction of exotic species. Economic concerns were as important as aesthetic, and botanists were careful to focus on seeds from similar climes.

The researchers found no records stating exactly when lantana arrived in India. However, the earliest mentions of alien lantana appear to have been after 1800. The first reference can be found in a catalogue of plants, when Lantana trifolia was donated by the Baptist Missionary William Carey to the East India Botanical Garden in 1809.

With the British continuing to establish botanical gardens across India—Pune (1828), Lalbagh (1857), Nilgiris (1874), Darjeeling (1878)—lantana began its march across the colony. Soon enough it spread from the botanical garden to surrounding areas. A book on flora in India by Dr. Dietrich Brandis, The Forest Flora of North-West and Central India (1874), identified lantana outside a botanical garden. A herbarium record of Lantana camara was made in 1887 in the Nilgiris. It was also recorded in Pachmarhi, Shillong, Mussoorie, Camba, Kouduru, Delhi, and Quilon. The Indian Forester and The Gazetteer of India recorded several instances of lantana in that period.

Part of the reason why lantana spread widely was that it was seen as an excellent hedge plant, used to fend off wild animals. It is, in fact, toxic to animals.

***

Old timers in BRT recount how rare

it was to see lantana even 30 years back. Now it is all over the forest,

strangling native plants. These changes have affected those collecting

non-timber forest produce the most.

M. Chandrigegowda, a resident of Muthudagaddepodu in BRT says he regularly went to the forest with his parents to collect lichen, amla and honey. “We could just walk to the tree, collect it and come back. It was as easy as that.”

Now lantana has covered the entire area. “Walking over the growth is extremely difficult as they have grown as tall as me. At many places, you need to crawl, for over a kilometre in some places, under the dense lantana growth to reach the big tree,” he says. For many, forest produce contributes about half their annual income.

Achchugegowda believes the effects are more insidious. “Today, the scent (of the jungle) is gone. Plants don’t grow well. Even grass doesn’t grow. Today, we girijana (people of the forest) have diseases, even the animals have diseases. Today, you see elephants, they look weak. They are just a bag of bones. They don’t get enough food. There is nothing left in this forest. All we have is lantana.”

***

Lantana was brought to Coorg or the Kodagu

region by a missionary as a hedge plant, but it soon escaped into the forests.

The invasion was severe. In 1893, a forest officer wrote that hundreds of

coffee estates had to be abandoned due to the lantana invasion in Coorg.

Its invasive potential was identified early. The Gazetteer of Mysore noted that lantana grew with “the rankness of weed” in 1897. The Imperial Gazetteer said lantana was spreading in Bengaluru in the 1900s.

Early editions of the India Gazetteers and The Indian Foresters Journal also found that lantana’s spread was facilitated by forest disturbances such as logging and clearing. This has been corroborated by recent research.

In Coorg, the situation had got so bad that mechanical intervention—cutting, burning, and uprooting—became necessary. Between 1911 and 1914, these activities were complemented with planting of bamboo in Savanthavadi, Maharashtra.

In Coorg, the situation had got so bad that mechanical intervention—cutting, burning, and uprooting—became necessary. Between 1911 and 1914, these activities were complemented with planting of bamboo in Savanthavadi, Maharashtra.

An early attempt to eradicate lantana was made in 1893. The cost was huge: ₹7,413 per sq km in the first year, and ₹2,471 and ₹1,235 per sq km in the subsequent two years.

By 1912, it was estimated that lantana had infested 284 sq km of private land, 161 sq km of government waste land, and 299 sq km of forest land. The government drew up an eradication plan but World War I put the scheme on hold. It was a long term plan, drawn out over a decade at a cost of ₹4.4 lakh. The government even passed legislation—the Coorg Noxious Weeds Regulation. The forest officers of Mysore, Madras, and Central provinces were worried about the impact on commercial timber such as sandalwood and teak. The Deputy Conservator of Forests in Coorg, A. E. Lawrie, wrote that sandalwood sown with lantana had been completely “smothered” in less than three years. It was the most troublesome in Wayanad and Coorg where it was impeding the growth of grass.

Even in the early 20th century, lantana’s invasion was progressing at a fair pace. In four forest ranges in North Salem, between 1917 and 1931, lantana spread at the rate of 600-1,280 hectares per year. Another paper estimated a spread rate of two km per year between 1911 and 1930.

“They observed that lantana was a light loving plant and thrived in areas where the forest or woodland canopy was incomplete and that it threatened the existence of the forest,” wrote Kannan in his paper.

The interviews with forest officials revealed that lantana was widespread even by the 1950s and 1960s. Around 90 per cent of them reported that lantana was present when they took charge, but the proportion remained consistent—there was no significant increase or decrease in its population in the next two decades. This could have been because lantana had invaded all the suitable areas by the mid-1900s.

Kannan’s paper also mapped the first sightings of lantana across the Western Ghats by forest officers. By 1950, the southern Western Ghats, as the experience in Coorg showed, had been covered by lantana, while the central and northern regions showed only some incidence. But by the second or third decade, these areas also saw increasing sightings, and they now occur commonly across the Ghats.

This was reflected when the inhabitants of these areas were surveyed. In the southern Western Ghats, the Soliga and Palliyar tribes said they had seen lantana even in their childhood, with increasing density over the decades. In the Bimasankar Wildlife sanctuary, the Mahadeo Koli tribe said lantana had not been observed even as early as 25-30 years ago. But the last decade or so has seen a huge proliferation.

***

What makes species invasive? Over the last 25 years research in biological

invasions has led to models that explain the phenomena. One way to think of the

invasion is to treat the process as a series of stages. In each stage the

invasive species has to overcome barriers before it passes to the next stage.

Lantana’s invasiveness in India can also be examined with the aid of these

models.

Some stages such as transportation and introduction are easily overcome, as human intervention such as the East India Company’s drive to import plants to India took care of that.

Other stages such as establishment depend on the adaptability of the species. Lantana is an extremely adaptable plant. It grows in a wide range of habitats—from sea level to mountains, rainfall areas between 1000-4000 mm per year, and different kinds of forests. Geetha Ramaswami, who has been studying lantana for the last decade, says it possesses a suite of traits that helps it persist in habitats not conducive for growth.

“Lantana can re-sprout after cutting, right back from the base,” she says. “That’s an amazing trait. Because even if your current plant body is cut, you can still produce shoots that will have flowers and fruits and get dispersed.”

Lantana also tolerates drought conditions better than many native species. Bharath Sundaram, who teaches at Azim Premji University in Bengaluru, and whose research interest includes invasive species management, says lantana has evolved in its competitive abilities outside of its native range.

“It can survive in really nutrient-poor conditions, but probably use even available nutrients in a far more efficient way than native species can. It can maintain some above ground life,” he says. In peak summer in BRT, he says, “You’ll find the upper reaches of the plant are all dead and dried up. But the closer you get to the ground, the plant is very much alive.”

Lantana also has practically no natural enemies, unlike in its native habitat. “There’s nothing that eats it up—no pathogen or herbivore that eats the seeds and the leaves, causing substantial damage so that the plant dies,” says Ramaswami.

The other barrier that lantana needs to overcome is reproduction. And this is the reason it has been so successful. Lantana starts seeding quickly, within six to eight months of planting. Sundaram says, “Lantana is able to produce multiple crops every year, and each crop on an average small plant can produce 1,000 to 5,000 fruits.”

The final stage for a species to become invasive is to be successful in spreading across ecosystems, and here lantana’s large fruit production is a big advantage. The ripe fruit is dark purple in colour and sweet—popular among birds such as Red-vented bulbul, red-whiskered bulbul, rose-ringed parakeet, thick-billed flower-peckers, jungle babblers, cinereous tits, and common tailorbirds.

Ramaswami’s paper published in 2016 found that even in forest zones where lantana growth is aggressively controlled, it is susceptible to seed dispersal by birds.

Lantana also utilises soil seed banks, which can remain dormant while conditions are unfavourable, but sprout when favourable conditions appear. “Let’s say a tree falls somewhere, or the soil is churned because of uprooting, or a rainfall event. It presents a perfect opportunity for this bank to be used,” says Sundaram. His research found that lantana seeds comprised nearly twice the number of seeds of all other native woody species combined.

***

The relationship between fire and

lantana has intrigued researchers. Bharat Sundaram says, “My primary interest

was not lantana when I began, it was more on forest fires.”

Fires play a major role in shaping the Western Ghats. The nature of these fires has changed, and the frequency has increased over the years. A study led by Narendran Kodandapani found that in the Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, frequency increased threefold between 1909-1921 and 1989-2002. It is estimated that in 1989-2002 the average period between fires in a forest in the Western Ghats was five years.

The paper concluded: “The current fire regime of the Western Ghats poses a severe and persistent conservation threat to forests both within and outside protected reserves.”

Forest fires have a tremendous impact on the nature and composition of forests. Before human intervention, forest fires, though infrequent, could be catastrophic, and this process would self-select trees that could withstand fire. Grasslands that have the ability to quickly regenerate, trees that shifted biomass to below ground level to protect itself, and those with thick spongy barks, thrived in these conditions, and became resistant to low intensity fires.

Sundaram’s initial foray into lantana was a paper in 2005 on whether forest fires aided the invasiveness of lantana. The paper, co-authored with Ankila Hiremath, proposed a fire-lantana cycle hypothesis. This theory supposes that lantana is a fire-enabled or fire-adapted invasive species, which regenerates readily in a forest fire. Lantana is an extremely flammable shrub, and—given the plants’ propensity to reach the canopy—can cause a devastating crown fire if it burns.

Sundaram and Hiremath proposed that fires facilitated lantana invasion, and that this created a positive feedback loop. “Lantana, once established, fuels further fires, setting up a self-feeding fire-lantana cycle,” the paper states. It argues that areas with shifting cultivation in the BRT Hills till the 1970s are now associated with high lantana density—an indication if not proof of this hypothesis.

Lantana, they said, has high tolerance to being burnt. Studies showed that re-growth of lantana turned denser in response to being burnt. This in turn yielded more biomass, providing more fuel for future fires. Native species—which can tolerate low intensity fires, but not the high intensity ones that lantana typically instigates—would not survive. “Thus forests colonised by lantana could well fall victim to a fire-lantana cycle, perpetuating lantana to the detriment of other vegetation,” the researchers concluded.

In the next phase of their work, Sundaram and Hiremath investigated what factors affected colonisation by invasive species. “Is there any ecological process that created this pattern, was the next set of questions that we tried to ask,” says Sundaram. Propagule pressure, or the amount and frequency of flowering and fruiting and habitat suitability were among the factors they studied.

But the one that Sundaram’s team looked at in depth was forest disturbances. Invasion theorists have long held that forest disturbances play a major role in the propagation of invasive species. “I was trying to see which of these disturbances play a defining role. Lantana invasion is a monolithic word, which you need to break up. It’s not just one day it’s here and the next day it’s there. There are stages,” he says.

To test this, data on the presence and density of lantana from 134 plots spread across a 540 sq km landscape was mapped against the disturbances for the duration of the study (1997-2008). Each plot was a two by two kilometre grid, and data on each plot’s proximity to lantana and fire maps for the study period were compared.

The result was surprising. Lantana density increased more than three times in this area. But not all plots showed the same pattern. Plots that saw a forest fire in those years either showed very little change in lantana density, or showed a decrease. Change in lantana density and fire frequency appeared to be negatively related.

“So we had expected fires to increase lantana invasion. Because it creates hot fires, it burns everything else, and lantana is able to come back,” Sundaram told me, referring to his 2005 paper on the fire-lantana cycle hypothesis, “More the fire, more the lantana density, because lantana is easily bouncing back from a fire, which is able to produce larger biomass that creates hotter fires, and this would perpetuate a lovely fire-lantana cycle.

“But when we looked at the empirical data, the relationship was exactly in the opposite direction.” Fires were in fact keeping Lantana down. Many plots that had burnt more than two or three times in that decade of study actually showed a reduction in lantana density. It appeared lantana does not cope well with fire as was thought before. “After all if you go to its native habitat in Brazil, it is not fire retardant at all. It’s a very nondescript small plant affected by fire,” he says. “So that means it’s retaining some of that character.”

Sundaram concedes that there are gaps in his research. “We don’t know whether native species went down in these plots or not. And I also don’t know if the fires documented were intensive or not.”

But the results are consistent with what has been observed in Australia—that frequent fires prevent, rather than encourage the spread of lantana. Indian forest management has traditionally regarded fires as detrimental in managing forests, barring certain grasslands in the northeast.

This is where the third piece of Sundaram’s work comes in—a look at how local knowledge views the invasion. Sundaram co-authored another paper in which the scientists interview the Soliga about what they think of lantana and why the invasion took place. They interviewed 47 men from the Soliga community aged 35-65 years.

They attributed lantana’s success to its high fruit production, but they also believed the change in fire regimes after 1973, when BRT was declared a wildlife sanctuary, was a big factor. With that declaration the Soliga practice of shifting agriculture came to an end as setting forest fires became illegal.

The Soliga felt fires suppressed lantana because “fires killed young plants as well as seeds present on the soil surface”. The drying of the soil from the fires also inhibited the growth of lantana.

Achchugegowda explained how these low intensity, low height, quick fires worked.

“We’d do this only in January or February when plants have moisture (which would minimise the exposure of plants). They would slash the plants till about half to one foot and burn them. After rain, the ground is filled with new grass and plants.”

They would not practise it in March or April when the sun is hot and the plants are dry. “It’s dangerous. Except in January-February, burning grass is dangerous. The whole jungle could catch fire,” Achchugegowda says.

Sundaram says in those months there’s a lot of dew in the forest, and the fire is smoky rather than the blaze seen in bone dry forest.

The Soligas believe fires are important to the health of the forest. Native species are unaffected as they have historically been exposed to low intensity fires. Moreover the fires do not burn the saplings of native species, only the litter. These fires clear the understorey, and the Soligas believe a healthy forest needs a clean and clear understorey.

***

But even the Soligas believe it is

too late to control lantana by fire. The biomass lantana has added over the

years would change the nature of fires. “They burn hotter and longer,” says

Sundaram. The Soliga believe their forests can withstand fire every year if

it’s of low intensity, but not a high-intensity fire.

But if physical removal is combined with fire control, there is a possibility of success. “In Australia, it’s worked,” says Sundaram. “It’s working. Physical removal plus fire.”

This has to be repeated several years. “You can’t do it just one year and expect changes. Year after year after year after year. For five, six, seven, eight years, then you might start seeing [results]. You’re talking about a decadal time frame,” Sundaram says.

The initial costs are high—physical removal is very hard. But the fires are cheap. Convincing the government and forest department, for whom fires are anathema to forest management, will be difficult. Government efforts to manage lantana and invasive species are yet to go beyond management at the level of the individual forest. Several cells and schemes have been put on paper, but these efforts are yet to show any results. A special cell set up for invasive species management by the Indian Council for Forestry Research and Education since 2009 is not much to show for itself. India is yet to have a law dealing with invasive species.

The Soliga point to the controlled burning the forest department itself does on the periphery of forests. “Why can’t it be done a little bit inside the forest? We have been asking the government to experiment [on a small scale]. Give us 1,000 acres, don’t pay us, we will use controlled burning and show you the result,” Achchugegowda says.

Researchers are not optimistic that about this experiment yielding fantastic results, but for Achchugegowda and his tribe it is a matter of faith. “This is a sacred forest. Jadeappa, my family god, resides in the forest.”

He recalls the days when they would offer flowers to their deity. “We never carried garlands from home. After the rain, when the forest was in full bloom, we would go inside the forest, collect flowers,” he says. “Parmatama, where you reside, such a beautiful place it is, what fragrance, the fruits we offer to you, the milk, the water, everything is given by you from this forest.”