The Russians started

2006 in Syria with a bang, really big ones. Hours into the new year they

launched a series of airstrikes over the country. Proud proclamations were

sounded from all quarters with a bold announcement: “A total of 311 sorties

have been made over the first days of 2016 during which strikes were delivered

at 1,097 facilities,” said Lt. General Sergey Rudskoy, the Russian defence

chief. They targeted oil facilities and infrastructure used by Islamic State of

Iraq and Syria (ISIS) militants in Raqqa, Dasmascus, Homs, Hama and a territory

they hadn’t ventured into before: Dera’a.

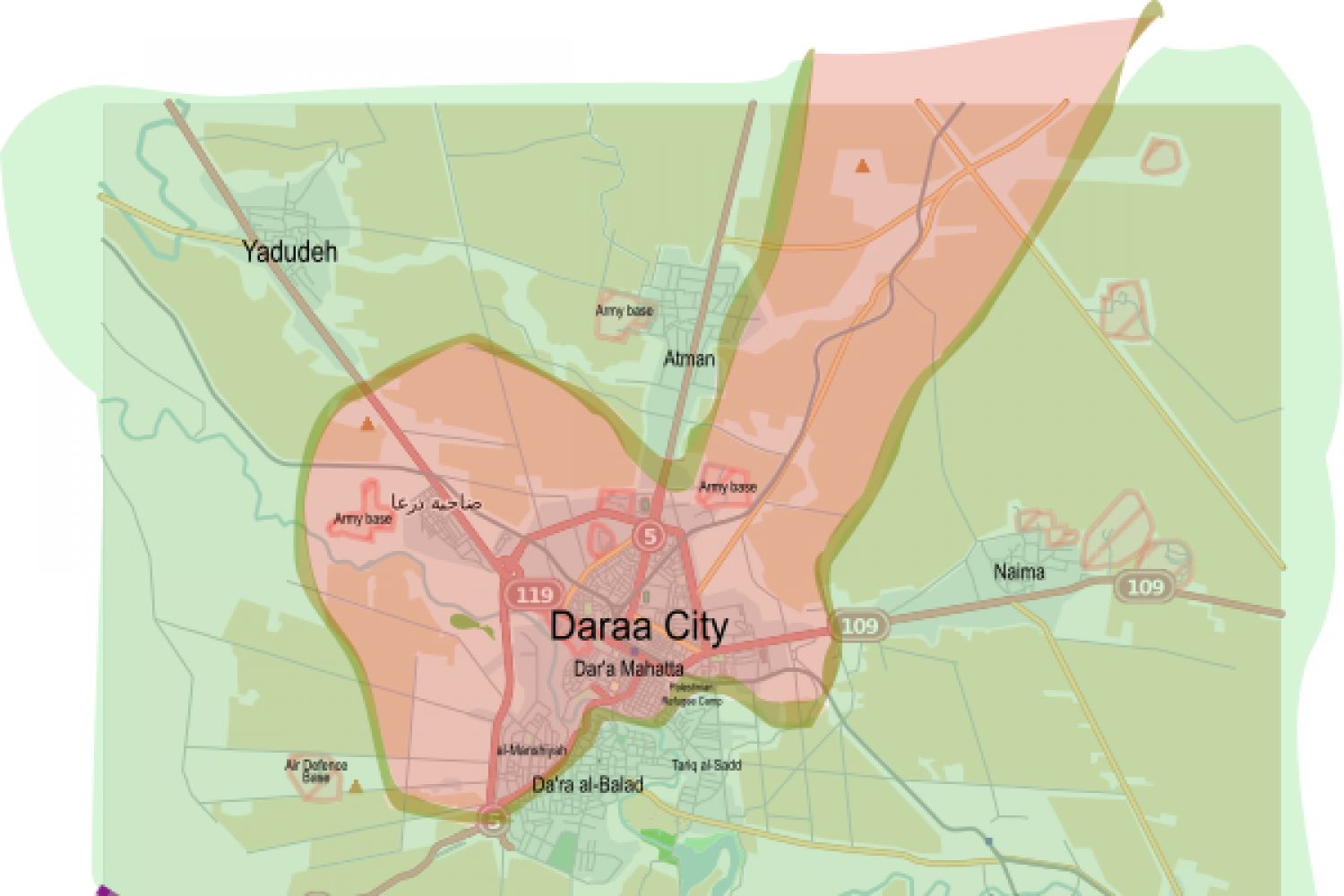

Dera’a had for long

been romanticised as home of the Syrian rebellion, the southern state that

dared to rise against the rule of Bashar al-Assad. For much of the war, Dera’a

remained firmly under the control of the Free Syria Army (FSA), the mainstream

opposition that liberated many of the villages in this southern state bordered

by Israel, Jordan and ISIS-controlled land to its east. Dera’a with its Free

Syria Fighters remained a low priority for a government preoccupied with ISIS

advances in the North of the country.

That changed

in May 2015 when ISIS marched on south Syria raised its black flag in

Dera’a. ISIS fighters went from house to house seeking FSA fighters. They

confiscated their weapons and publically shamed them as disbelievers. Mohammed,

a fighter with the Free Syria Army, witnessed their ruthlessness. “They said

they were the real Muslims not us,” recalls Mohammed. Soon ISIS went on a

killing spree beheading people and by the end of 2015 was in control of three

fronts.

Defections from FSA soon followed. Just last month one battalion of about 40 FSA fighters joined ISIS even though its presence in the area is limited. “They join ISIS for money,” says Mohammed. ISIS pays fighters about $300-400 a month from its deep coffers. It runs a highly lucrative business not just of extortion at checkpoints but also controls Deir Ezzor, the area with Syria’s most productive oilfields. Oil sales account for hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue and soon FSA fighters whose payment was in food for themselves and their families spoke about mass defections, according to a senior commander in the Free Syria Brigade in the southern front.

That’s when the Syrian

army and Russian jets turned their attention to Dera’a.

The beginning of the

year was marked by a new push in southern Syria with the help of Russian air

cover. This could be a potential game changer. The FSA fighters in Dera’a are

staffed by Arab and Western forces. Large numbers of its fighters have been

trained by Americans across the border in Jordan. “If this area falls to Assad

then the international community loses a major bargaining card. This is the

only area where the West has a healthy relationship with fighters against the

regime,” says a commander of the Ben Sunni brigade.

The battle is

currently focused in a town called Shaikh Maskin. It has been “hot” since the

first week of 2016. Days of assault by the Syrian army supported by the

heaviest aerial bombing campaign Russia has unleashed in southern Syria have

reduced the city to rubble. Buildings have collapsed on top of each other,

ceilings chopped off and wires and iron roof beams bent out of shape. Sheikh

Maskin is a trophy town, the “crossroad of the south,” as a Syrian General

called it, lying on a major supply route from Damascus south to Jordan.

The fighting in Sheikh

Maskin has led to a mass exodus. Thousands have fled from the villages. Israel

has a policy of not accepting Syrian refugees, the neighbouring state in Syria

is firmly under ISIS control so people fled towards Jordan. About 12,000

refugees were stranded on the border as of December 8, 2015, according to

estimates by the UNHCR. Jordan claims that 16,000 refugees are stranded in the

remote desert area. In December, Human Rights Watch claimed that at least

20,000 refugees were on the border and the UN refugee agency has urged Jordan

to allow them to enter. But the border remains closed. So the fleeing Syrians

are now trapped in this no-man’s land at a particularly bad point, when years

of strain have pushed the UN’s humanitarian agencies to the verge of

bankruptcy. They cannot meet even the basic needs of the millions of stranded

people. This refugee crisis is beyond them.

Sources in the

Ministry of External Affairs state that a key reason for the visit of Syrian

foreign minister Walid Muallem’s visit to New Delhi is to urge the Indian

leadership to launch humanitarian efforts in Syria from a base in neighbouring

Jordan.

This is Part III of

the Fountain Ink series on the Syria crisis. Read Part I here and

Part II here.

(Title image by MrPenguin20 via Wikimedia Commons)