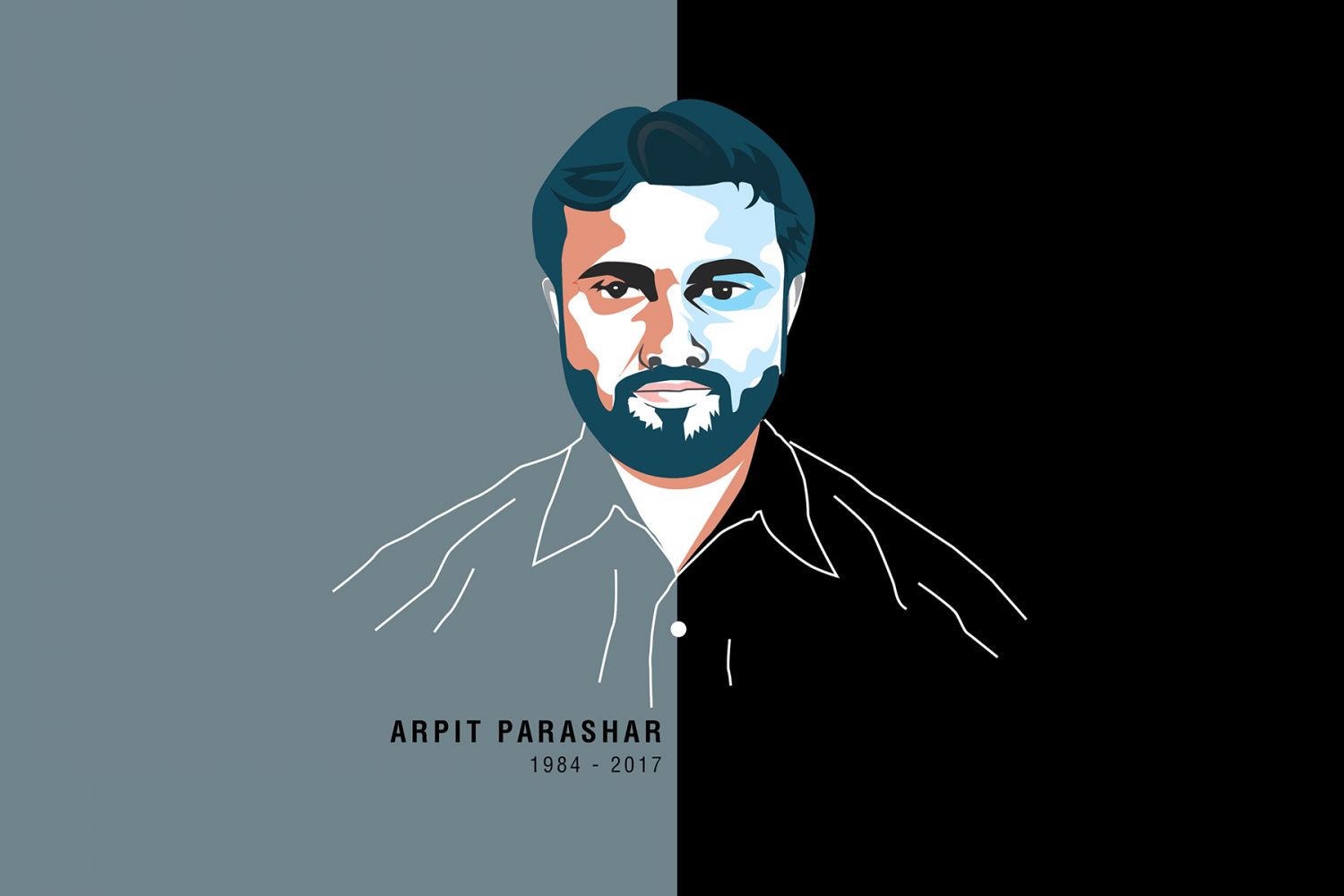

The last time Arpit Parashar spoke about his impending death to me was in 2014. It was a moonlit night on the Ganga, and he was on a boat smuggling country-made guns across Uttar Pradesh. It was the run-up to the general elections and the illegal arms trade had seen a boost. On the boat was an old man everyone called Chacha, his eyes pure violence and trained at the journalist who had hitched a ride. Somewhere in western UP, on the unpatrolled waters of the holy river, Arpit thought Chacha was going to throw him over. When death came, that’s how it would come for him: in the middle of a reporting assignment, when he had pushed the boundaries of a story that extra mile. It wasn’t going to be in a fall from the terrace of an apartment on a winter afternoon. That’s not how his kind of reporters go. Reporting was his whole life and, as far as he was concerned it, could be his death as well.

Most journalists are pathetic failures to their younger selves. They become the person they swore they never would—one who stopped caring, who was seduced by designations, one who unpacked his spine vertebra by vertebra and stored it in the vault of dead dreams. They become cynical, hollowed-out shells of their own promise. There are a few, like Arpit, who go all in. They lose jobs but don’t give up on journalism. They take the soul-sucking indifference of compromised editors and keep the fire burning. Above all, they don’t give up on the story.

For the eleven years that I knew him, first as a friend and later as his editor, reporting was his true north. He loved the chase, the travels through nameless towns and conversations with faceless people all of whom he brought to life in his work. Uncoiling layers of government lethargy drove him, the injustice and the unfairness made him bristle.

He never asked if his story was going to make the cover. It was the one detail he wasn’t curious about. “Oh, you are putting it on the cover,” he would say with amusement, as if he found the exercise slightly dubious. His stories made it to the cover of Fountain Ink seventeen times.

As a reporter his great gift was to get people to take him along. Off duty constables took him drinking, a bookie managing hundreds of crores in cricket betting set up camp with him in the desert, and a man poured his heart out with him in the living room while his wife and the gigolo he had hired for her had sex in the bedroom. Armed with notebook, pen, and a wry laugh he saw through them all.

It was not always easy being him. It was difficult to find jobs in Delhi. He didn’t belong to any clique, didn’t quote the usual suspects, and wouldn’t back off from a story. Then there were his own personal demons. The story saved him always, even as it consumed him.

Like all great reporters he hated the lazy opinion writing of scotch-drinking intellectuals, and the smugness of editors who had never stepped out of office. Like all great reporters he loved Urdu poetry and Old Monk rum. He left too soon, but he leaves behind in his work all that journalism should be.