According to the National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4), the Infant Mortality Rate in urban India is 29 as compared to rural which is at 46 per 1000 live births, while the under-five child mortality rate is 34 in cities and 56 in villages.

Stunting (low height for age) is prevalent among 38 per cent of our under-fives and the rate of wasting (low weight for height) of 20.8 percent among our underfives is the highest in the world. Reed-thin arms, the swelling from oedema distorting their body, some with distended tummies, others wheezing with pneumonia, and most of them with lacklustre eyes and scarcely able to move...this is the state of India’s children. While they may not all be dying of starvation before our eyes, millions are at risk of lifelong problems because their diet does not support their physical and cognitive development. Studies estimate that the situation will only escalate further in the years to come.

Many organisations are working to address this problem besetting the next generation and its dire consequences for productivity, but is help reaching the right people? What exactly lies at the end of the chain? How do the Integrated Child Development Services’ (ICDS) outreach programmes via Anganwadi Centres actually work? Are there any success stories that throw light on how things can be done right? It’s only by investigating conditions at the grassroots level that one can get answers that present the true and whole picture.

Assam: The gateway to the Northeast is rich in tea, silk and oil, and receives more rainfall than most parts of India. But many parts of the state are still underdeveloped and has a high incidence of poverty. The vulnerable groups comprise tea garden labourers, Bodo and Rabha tribes living in areas like the Bodoland Territorial Area Districts, migrant populations of the Brahmaputra floodplains, as well as predominantly Muslim communities in Darrang’s Kharupetia region. Assam is one of the bottom-five states of the country when it comes to health and hygiene. Undernutrition is rife among children, adolescent girls and mothers. The infant mortality rate is high at 48; and 38 per cent of children under five are stunted, primarily due to poor infant and child feeding practices, poor hygiene and sanitation. Fourteen per cent of children suffer from acute malnutrition, with four per cent falling in the category of Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM).

Chhattisgarh: It is one of the richest states in terms of minerals, ranking first in coal production. It is also one of country’s poorest states. A large number of inhabitants are tribal groups that often have nutrition-poor food habits, low literacy and subsistence-level economies. Besides, Maoists are active in many of the densely-forested districts of this state. According to NHFS-4, the population of Chhattisgarh has high levels of wasting (15 per cent) whereas a report by NITI Aayog shows that an alarming 37.6 per cent of children below five suffer from malnutrition and 41.5 per cent of daughters and mothers in the state are anaemic. Home visits in regions high in SAM children such as Dongargaon and other areas surrounding Rajnandgaon, and in the Manpur, Narayanpur and Kanker region gave unique insights into the issue.

Jharkhand: It possesses 40 per cent of the mineral resources of India, and is rich in everything from iron ore and coal to uranium, gold and silver. It registers a higher rate of economic growth than the rest of the country, but conversely, reports show that more than 40 per cent of the population lives below poverty line, about 45 per cent of children under the age of five are stunted, and almost 48 per cent are underweight. Tribals such as Hos and Santals make up a large part of the poorest groups in areas surrounding Chakradharpur.

Maharashtra: It’s India’s wealthiest and most industrialised state and the largest contributor to the country’s GDP (15 per cent). And yet, Maharashtra has vast areas where people suffer from scarcity of basic nutrients. Less than 100 km from Mumbai, Palghar district has become the epicentre of a SAM crisis over the last two decades. In 2015-2016, there were 555 SAM-related deaths, while the following year saw 475 similar deaths of children. In districts such as Nandurbar and Amravati too, the situation is dire. According to a state government missive, there were almost 94,000 children suffering from SAM in 2018, even though they assert infant mortality has been reduced by 60 per cent from 45 in 2003 to 19 in 2018. While the NFHS-4 reported that the prevalence of SAM in Maharashtra was 9.4 per cent, independent assessments suggest a higher figure. The population is largely tribal communities like Warli, Mahadev Koli, Katkari and Thaker.

Odisha: Its 9.59 million tribals making up almost 23 per cent of population, Thirteen of the 62 tribal communities belonging to Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs), certain pockets of the state show an alarming rate of malnutrition. As per UNICEF data, about 57 per cent of tribal children in the under-five year segment are chronically undernourished and infant mortality among tribal communities in Odisha is 92, higher than in the rest of the country. As many as 26,184 children suffered from malnutrition and fell in the severely underweight category in 2018. State Women and Child Development (SWCD) department data shows that the number of children suffering from malnutrition is the highest in the districts of Kalahandi (3,114), followed by Kandhamal (2,887) in 2018.

In Amatola village, about 56 km from Rajnandgaon, all houses have gardens with creepers heavy with gourds. Despite this, children suffer from acute under-nutrition. Ankit (18 months) lies on the floor. He can’t sit up or stand up for any length of time.

Customs and rituals

Much is said about India’s cultural continuity that gives us a sense of deep belonging. But its many archaic traditions are discriminatory and are harmful to many groups of people. Women are worshipped as goddesses but do not enjoy such status in the flesh. Although the menstrual cycle is natural part of life, it is considered unclean and menstruating women in orthodox families are often segregated from the family. In some areas, a new mother is isolated for up to a month after birthing her baby. The general suspicion of institutional healthcare sees many groups frequenting medicine men whose repertoire includes chants, talismans and dubious concoctions. Most of them approach hospitals only as a last resort in an illness, by which time the situation is usually beyond repair.

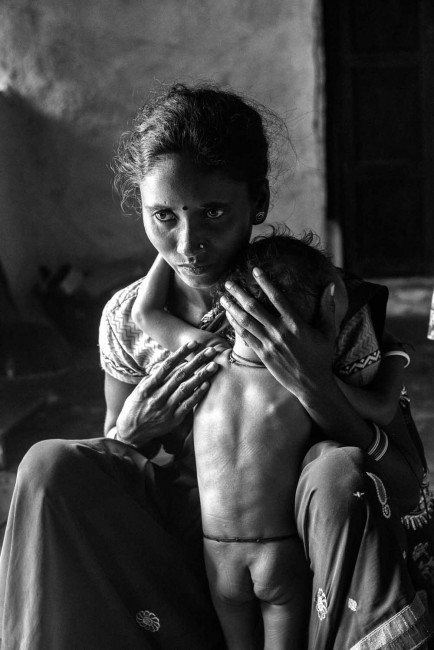

Lack of resources: Bajobai with her daughter Shivani, who is malnourished. Bajobai and Rajan are not married though they have been living together for 10 years in this homestead in Karketta, near Manpur in Rajnandgaon district. This live-in relationship among Gond tribals is called “paithu” and is initiated when a woman decides to move into the family home of a man she likes. The family is impoverished and nutritious food is scarce.

Away in a manger: The makeshift hut at Chawargaon in Manpur, Chhattisgarh, has an earthy smell that’s equal parts birth matter and cow dung. Made of bamboo and mud it stands away from the family home. Mother and child are fed through the doorway. No one is allowed inside for about a month. Urmila (27) delivered a baby girl more than 12 hours ago in the hut, as her family doesn’t believe in hospitals or doctors. She has fever. Her child weighs two kilos and 40 grams. Urmila, who lost two children before this, is low on hope. While she and her husband want to seek medical help and may have even opted for an institutional birth, her mother-in-law makes the rules and will not permit anything other than traditional tribal medicine or rites based on superstition. For the next eight days, Urmila will only get rice gruel. If she survives, the baby will be named after a month.

Assam’s deprived

In Assam’s Darrang district there is a Muslim majority in the outlying areas of Kharupetia town. This population, though literate, is beset by early/multiple marriages, violence against women, lack of birth control and spacing between children, extreme poverty and, in some villages, government failure to provide food supplies.

At the Anganwadi nearby, Mukhida Begum is with her son Murshidul Islam (3) who weighs only 8 kg, in the hope of getting him one square meal. Mujahidul Islam (almost 3) is with his grandmother Hanufa. This SAM child has pneumonia and weighs just 9.3 kg. His mother died in a fire a month after giving birth and his grandmother has looked after him ever since. Shahnaz Parveen (12 months) weighs only 5.9kg even though at birth her weight was 3 kg, as her mother Nazma has to work in the fields all day and cannot breastfeed her. Aakhirul Ali (seven months) had a birth weight of only 2.5 kg, which has since only increased to 5.5 kg. His mother Rabiya Begum says she is unable to breastfeed and he survives on rice, biscuits or cake, whenever he gets them. Siblings Aashiq Taluqdar (4) and Afrida (34 months) are with their mother Murshida Begum. Aashiq weighs only 11kg, while his sister has a normal weight of 12 kg. Their parents Murshida and Noor Islam are at a loss to explain why there is such a vast difference between the two.

Model Village: Nadirmukh village claims to be 100 per cent literate and has been adopted as a “model village” by Kharupetia College. But the living conditions are dismal. Early marriages of anaemic girls lead to early pregnancies and low birth weight babies. In a dark and dank hut, Jubeda Begum (17) lies on a dirty sheet on the floor with her eight-day old son. The baby, not yet named, is a month premature, with respiratory distress and congenital malformation, and weighed only 1.8 kg at birth. The grandparents–Jamila and Abdul Ahmed–hover around the mother and baby and have kept medical reports from the NICU safely. Anganwadi worker Anjuma begum tries to explain the basics of hygiene as well as nutrition.

Hand to Mouth: In Muamari, Omiron Nessa (22) and Sheikh Farid (24), are parents to Phoolbhanu (2.5 months) and are already expecting their next. Sheikh is a daily-wage carpenter. The couple married in 2015. They avail anganwadi services, family planning counselling and monthly rations of 3kg rice and 500 grams of peas.

NRCs are too few

The Union ministry of health and family welfare has established 1,151 Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres (NRCs) across the country under the National Health Mission. They provide facility-based care for children with Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) and medical complications. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS 4, 2015-16) estimates that 7.5 per cent of under-fives are severely wasted and 35.8 per cent are underweight. Children with SAM along with medical complications are referred from villages by frontline caregivers such as ASHA and anganwadi workers who make home visits. These facilities offer appropriate feeding, height and weight monitoring, and counselling to mothers and caregivers. There aren’t enough of these 10-12 bed centres, and sometimes the long wait for admission discourages parents. According to reports, 1.86 lakh children under five were admitted to NRCs in 2017-18. At least 1.17 lakh children were discharged with targeted weight gain.

Mourning Mother: Kandhamal is a backward forested area in Odisha. The children’s ward at the primary healthcare centre is full, most of the beds occupied by SAM children and premature babies. This mother from the Kaundh tribe was in tears. The nurse explained that her child had died that morning.

Birth on the Run: At the primary health care centre of Mokhada village in Maharashtra’s Palghar district, almost all the beds in the children’s ward are occupied by SAM babies. Archana Karpade (28) has been here with Ashwini (14 months) for the last eight days. Ashwini is severely underweight at 6.2 kg. The Warli tribal family owns a small patch of land where they grow millets. Archana had to work in the fields through pregnancy, missing out on essential rest and supplements. This harvest season has been especially difficult for her as she had to work long hours, leaving her daughter at home. Now, Archana waits as Ashwini has a long, hard battle ahead to gain her target weight.

Plantations of despair

Tea garden labourers make up about 20 per cent of the population of Assam, which produces more than half of India’s tea. The ancestors of the current workers were tribals and backward castes brought in from neighbouring states and made to work on British plantations from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. Their population is estimated at 6.5 million, a large number of whom still live in quarters provided by the 800-odd estates across Assam. They earn about ₹167 per day, with a few benefits. The women are at the lowest end of the chain. Many have to cope with violence in the home from husbands addicted to liquor, work through their pregnancies, and return to work soon after childbirth, thus denying their babies nutrition through exclusive breastfeeding. The women who don’t have extended families are forced to take their babies to the tea plantation as they have no access to daycare facilities.

Mighty River: As you approach the hut built on an embankment, you can see where the mighty Brahmaputra’s floodwaters have left a line on the mud before receding. For now, the family is counting its blessings that they didn’t lose a lot in the inundation this year. The two women who sit on the porch surrounded by their brood could easily be dismissed as people past their prime who are just eking out the end of their life. But you couldn’t be more wrong. Both are permanent tea garden labourers whose position at Maijan tea estate has brought their family multiple benefits. One’s son Nandan Bhuyan works as a carpenter and is married to the other’s daughter

Helpless at Home: Swapna and Suresh Bhumiz work in the tea gardens near Moran in Dibrugarh, one of Assam’s biggest teaproducing regions. They earn a combined salary of about ₹1,200 a week, to feed five mouths. Their twins Deep and Arati (11 months) are both under-nourished, having started life with a low birth weight. Their grandmother says the boy is even worse off as he doesn’t suckle properly. Their older brother Naren (3.5) sits swaddled on the bed. He suffers from scabies but the family doesn’t have money for medical treatment or to help his siblings.

Trapped in old realities

Although there are educational, professional and political reservations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, a large proportion of those who live in remote rural areas are cut off from these reformative measures. Their reality hasn’t changed and they are stuck in the traditional roles their clans have served since long. And while the men have a hard time, it’s women that suffer the most, receiving the least medical attention and nutrition.

A Grim Harvest: The village of Chawad in Chhattisgarh is hard at work in the fields or carrying bundles to their storage rooms. Satrupa and Premlal Sahu take turns to work in their family’s fields while the other looks after their two children. Tushar (9) is active though underweight. And their toddler Lokprabha (18 months), who was only two kg when she was born, is now just 8.5 kg. The parents have taken her into Dhamtari town for check-ups. The doctors tell them there’s nothing wrong but they are tense as her weight doesn’t go up whatever they do.

Caste at Work: Kohokatola village in Chhattisgarh’s Kanker district is clean and prosperous looking, except when you turn a corner and come upon the home of the local blacksmith. Bhagiram struggles to make ends meet. Belonging to the Vishwakarma Lohar caste, his family faces discrimination from the higher castes in the village. That is why his wife Hirakali is reluctant to send her daughter Durgeshwari (4) to the Anganwadi. She and her older brother Bhakt Prasad know how to work the bellows and enthusiastically keep the fire burning, which helps their father in his work. The youngest child Jageshwari (18 months) hasn’t benefited from her visit to the NRC.

A Forest of Obstacles: Nimanjali Durga (25) has three children and is expecting her fourth in six months. Although bleeding from the ears, she can’t go to the hospital as nobody is ready to accompany her over the long distance, which involves crossing a thick jungle and a river. She is waiting for her husband, a cowherd, who takes the entire village’s cattle to graze from 9 am to 6 pm daily. For this, he is remunerated in rice. No rations or anganwadi workers reach these people who live in this remote hamlet inside the Karlapat Wildlife Sanctuary.

Correction, Jan 13, 2020: The caption beginning "Mighty river" was attributed to the wrong image in the print version. It has been corrected online.