Everybody knows that

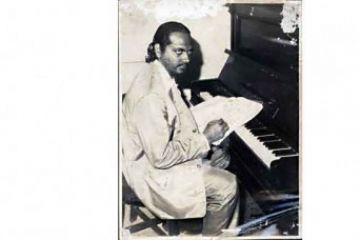

Maqbool Fida Husain (September 17, 1915-June 9, 2011) was independent India’s

most celebrated artist. And we also know that he died in exile, forced there by

an avalanche of court cases filed by people who objected to his depiction of

Hindu deities, describing his work as offensive to Hindu sensibilities.

He leaves a huge body

of work—a fair part of it memorable. His superb line-drawings and dynamic

paintings are an integral part of the visual memory bank that

Continue reading “Husian and the eternal feminine”

Read this story with a subscription.