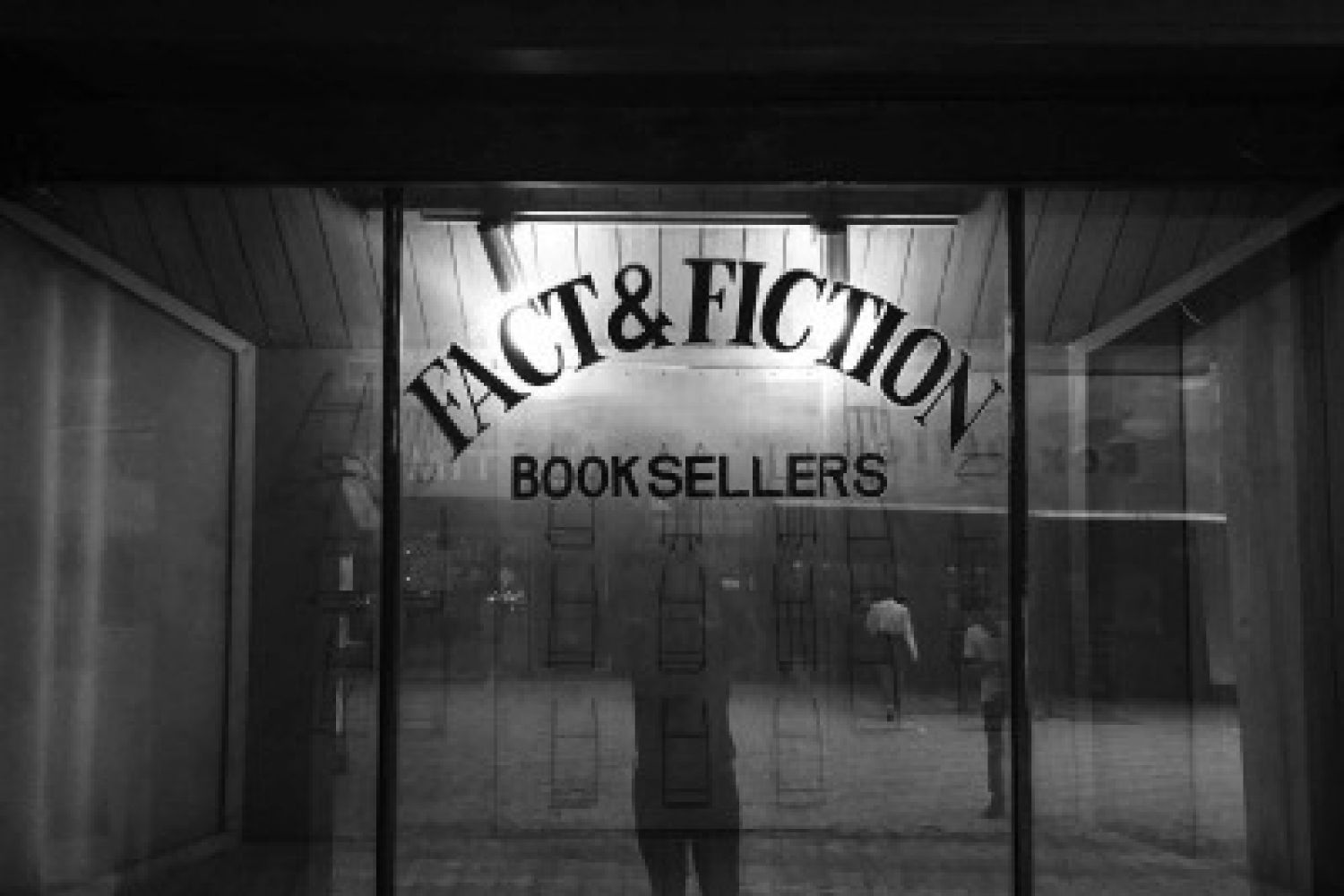

On the Friday that rain and a traffic jam brought Delhi to a

standstill, I was crouching between bookshelves in Priya Market digging out

several J. M. Coetzees that I hadn’t been able to find online. The bookshop was

Fact and Fiction, whose impending closure had been recently announced. That day

was August 7. It eventually closed on August 23.

Coincidentally, Fact and Fiction was the first bookshop I

ever visited in Delhi. I had just joined a television news channel yet to be

launched,

Continue reading “Reader’s indulgence, yesterday’s dream”

Read this story with a subscription.