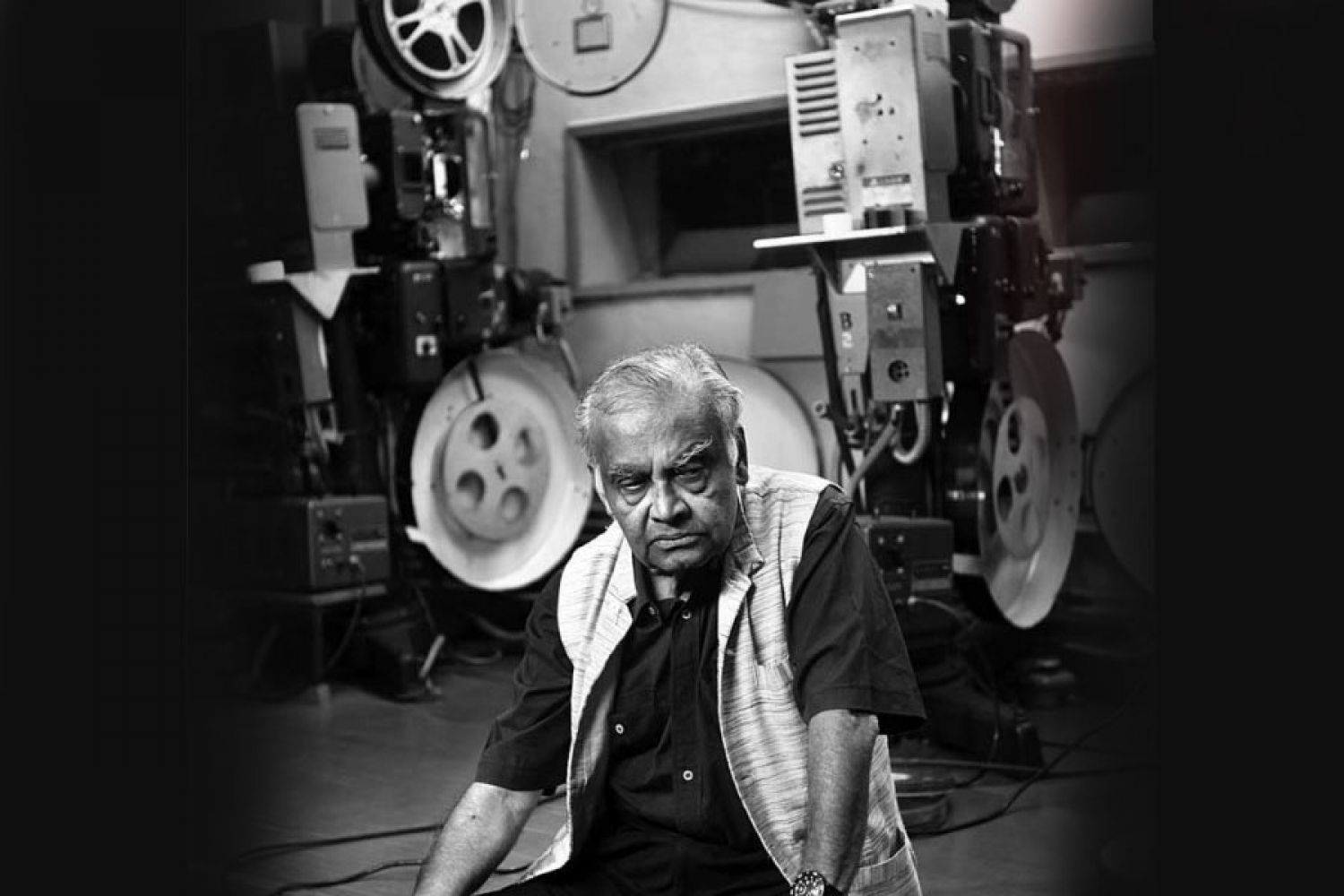

Cinema is about time

and its fragments, orchestrated to produce a harmonious whole through a

narrative. The results depend upon the talent of directors but what they create

is a record of the world in action in a span of time, and therefore deemed

worthy of preservation in an archive so that viewers can perceive the world and

its goings on in particular moments of human history as seen by a certain film

maker. In order to make preservation and viewing of films from the past,

distant and no