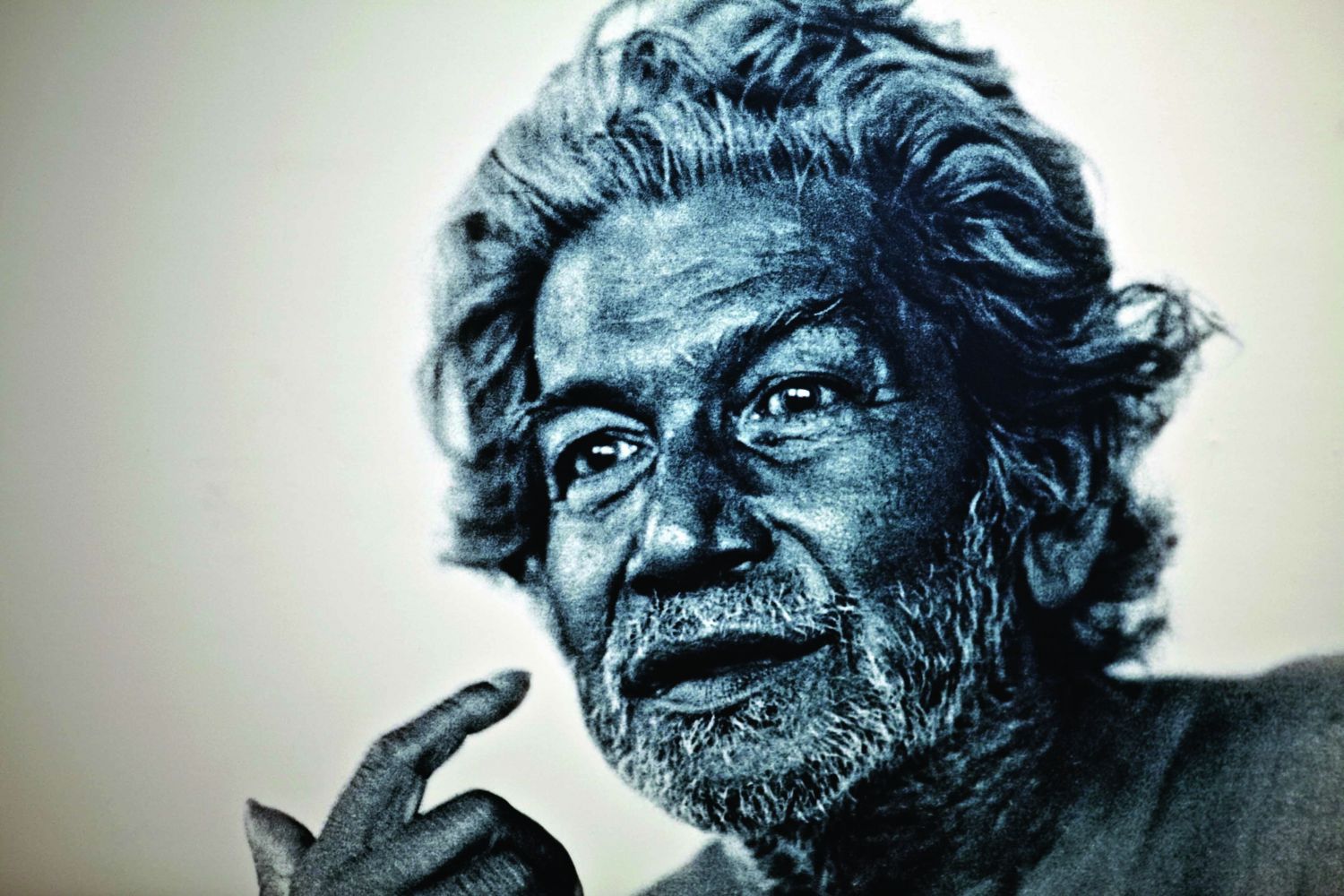

Ramkinkar Baij

(1906-1980) was an artist’s artist, and therefore little known in his own

country, where art is largely the pre-occupation of the microscopic elite. The

National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, under the stewardship of its

director Rajeev Lochan, has done a signal service to the nation by organising a

huge retrospective exhibition of this great master, who had all but faded from public

memory.

He belonged to the

barber community and ordinarily there would have had lit