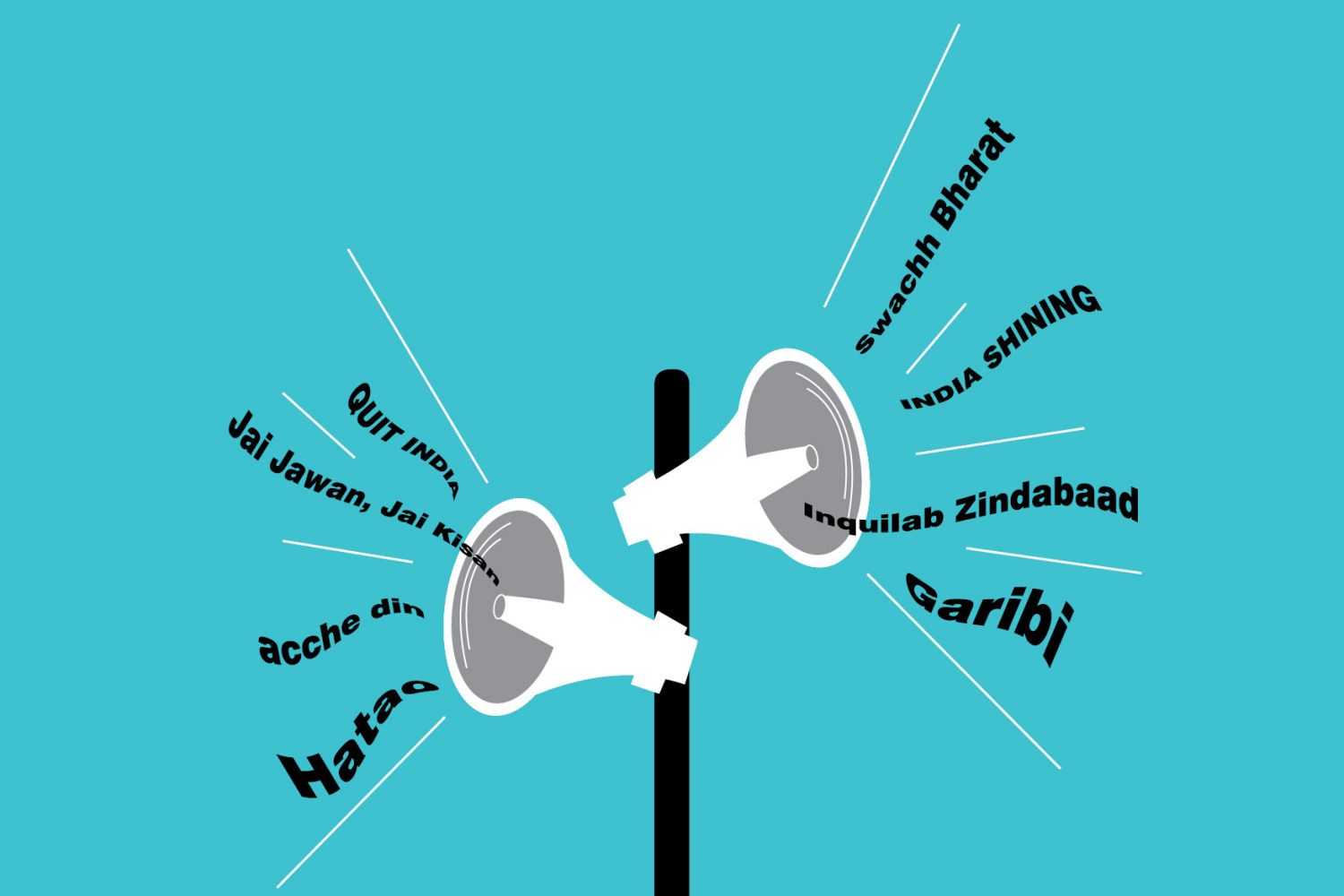

A subaltern stasis was

developing towards the second half of the Sixties. Then, as now, wealth was

shunted up. While the government’s economic policies produced limited growth,

the political structures prevented fair distribution of even that growth.

The poor were reeling

under rising prices and prime minister Indira Gandhi knew it. She was also

aware of the Naxalite movement spreading across the country and the Left’s

ideological support. Her own situation was uncertain with the Co