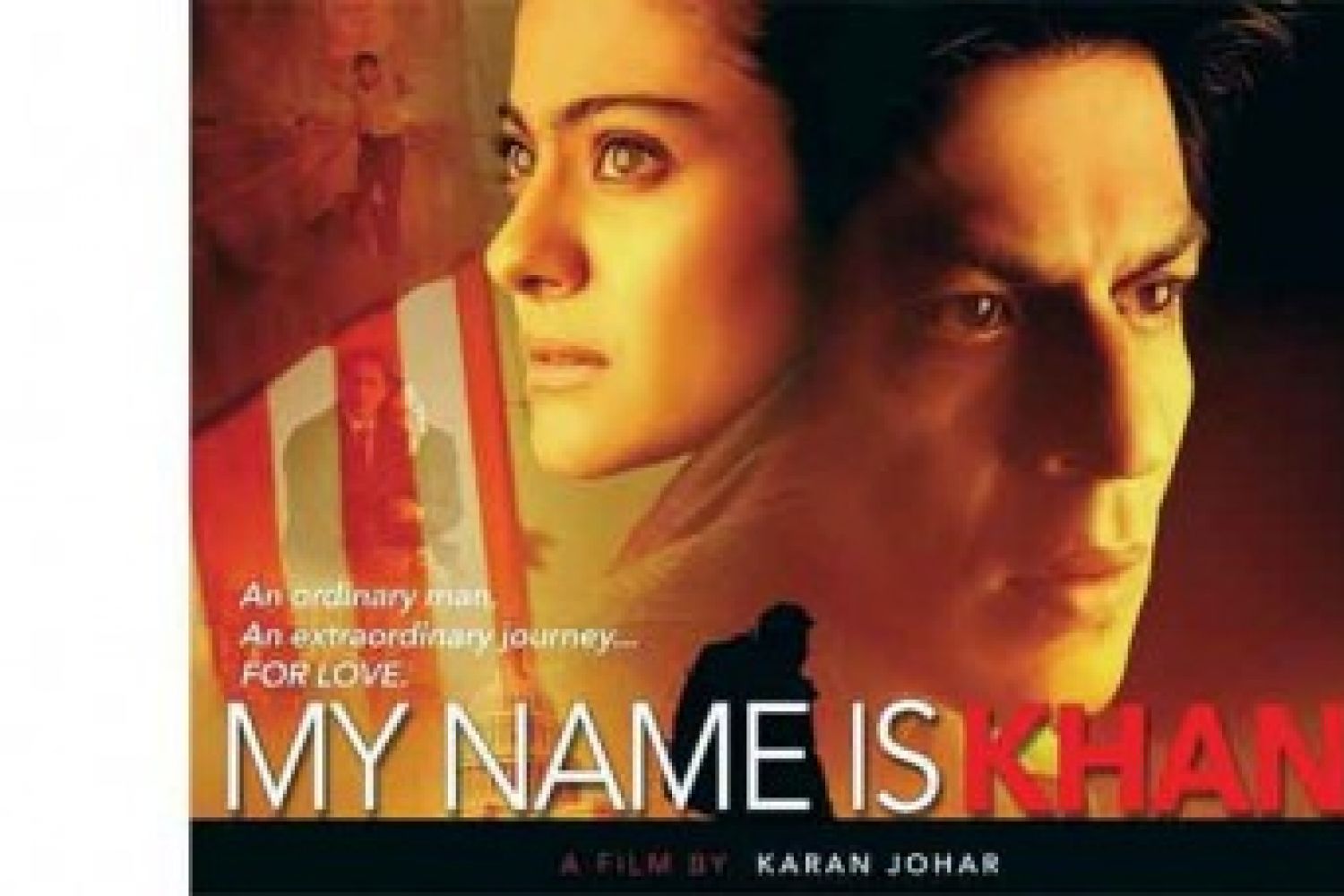

Everyone loves glamour,

but in Pakistan, the desire for some relief from the veils drawn down by the

ultra-conservative is especially strong. No wonder, then, that Bollywood has so

many fans. It draws attention to something specific, something that signifies

happiness, joy and celebration. Lollywood—the Lahore-based Pakistani film

fraternity—may have had glamour at some point in the past but what they make

today in the name of a film is not what the Pakistanis want.

Bollywood is the