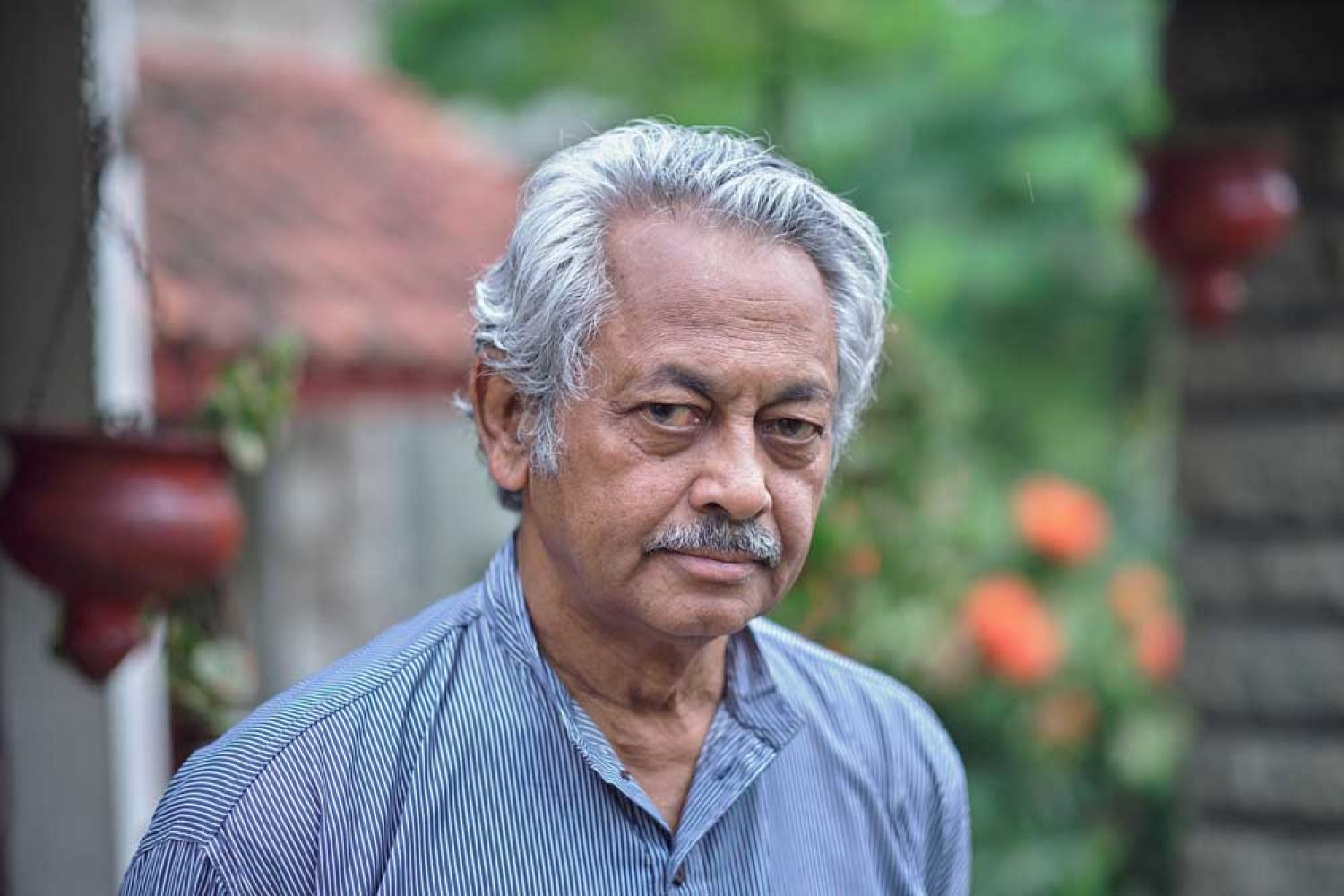

One of the pivotal figures to emerge from the Indian parallel

cinema of the 1970s, Girish Kasaravalli might well have ended up in a career in

pharmacology. While training in Hyderabad, he came across an advertisement by

the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) and applied.

His stint at FTII provided an inkling of the success he

would see. He graduated with a gold medal, and his student film Avashesh

was awarded the National Film Award for the best short fiction film. And in

1977

Continue reading “'I don't know how producers make money'”

Read this story with a subscription.