Anuradha Roy wears

several hats rather nattily. After a long career as a books editor and

journalist, she opened an independent press, whicha she runs with her husband,

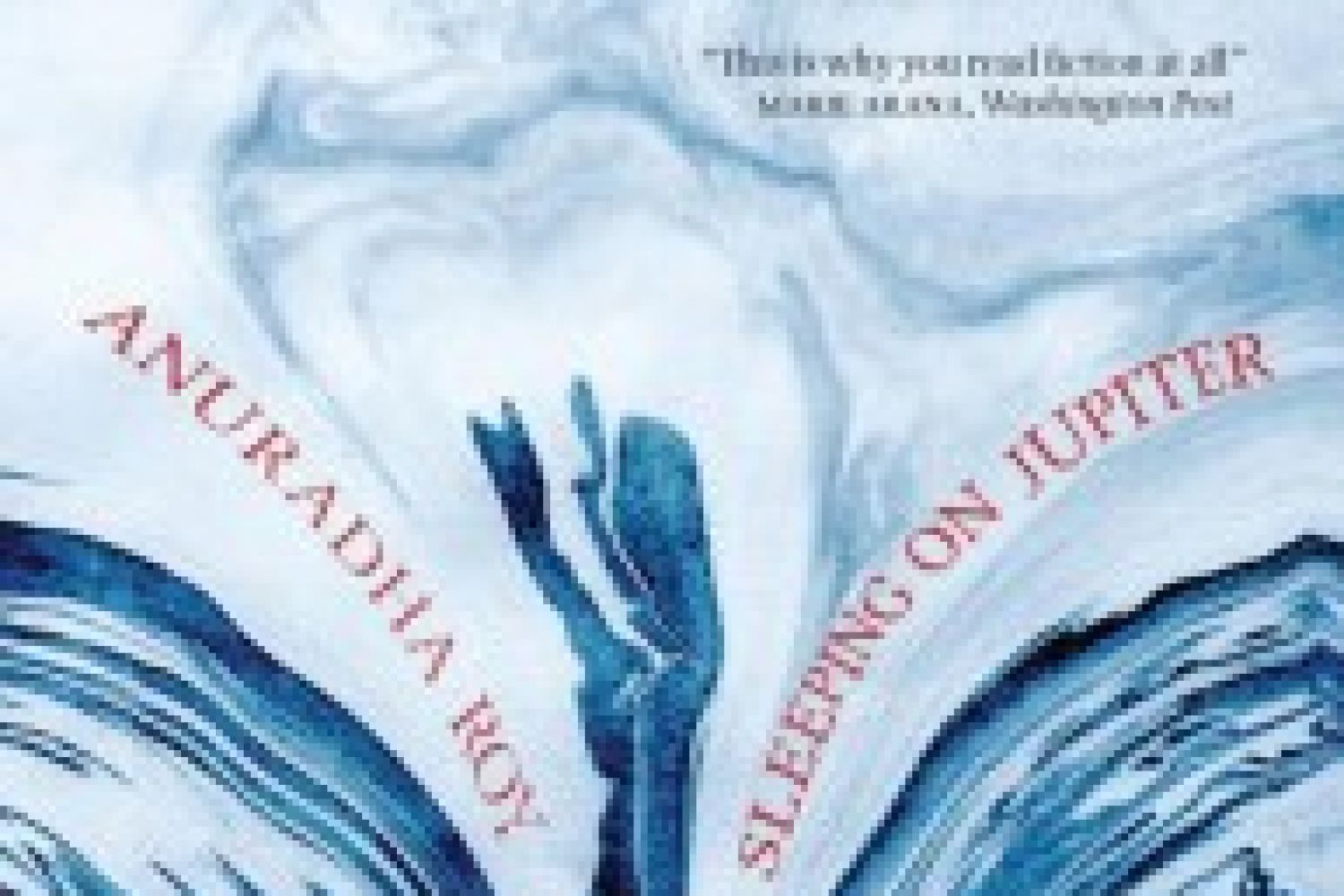

Rukun Advani. She is a designer, essayist, and novelist. Her first novel, An

Atlast of Impossible Longing, which traces two forbidden romances through

several decades in the early twentieth century, was shortlisted for the

Crossword Prize 2008 and Shakti Bhatt Prize 2009. Her second novel, The

Folded Earth, which

Continue reading “‘I never thought I’d write a novel’”

Read this story with a subscription.