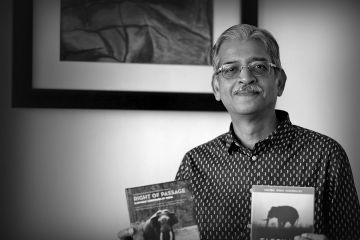

Mahesh Rao’s debut

novel, The Smoke is Rising, won the Tata First Book Award and was

shortlisted for several others, including the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize and

the Crossword Prize. His second book, One Point Two Billion, is an ambitious

collection of short stories, set in various locations across India, and has

been greeted with rave reviews. In this interview, the author chats about the

other Naipaul, books that need to be carried on wheelbarrows, and what he has

in common with B