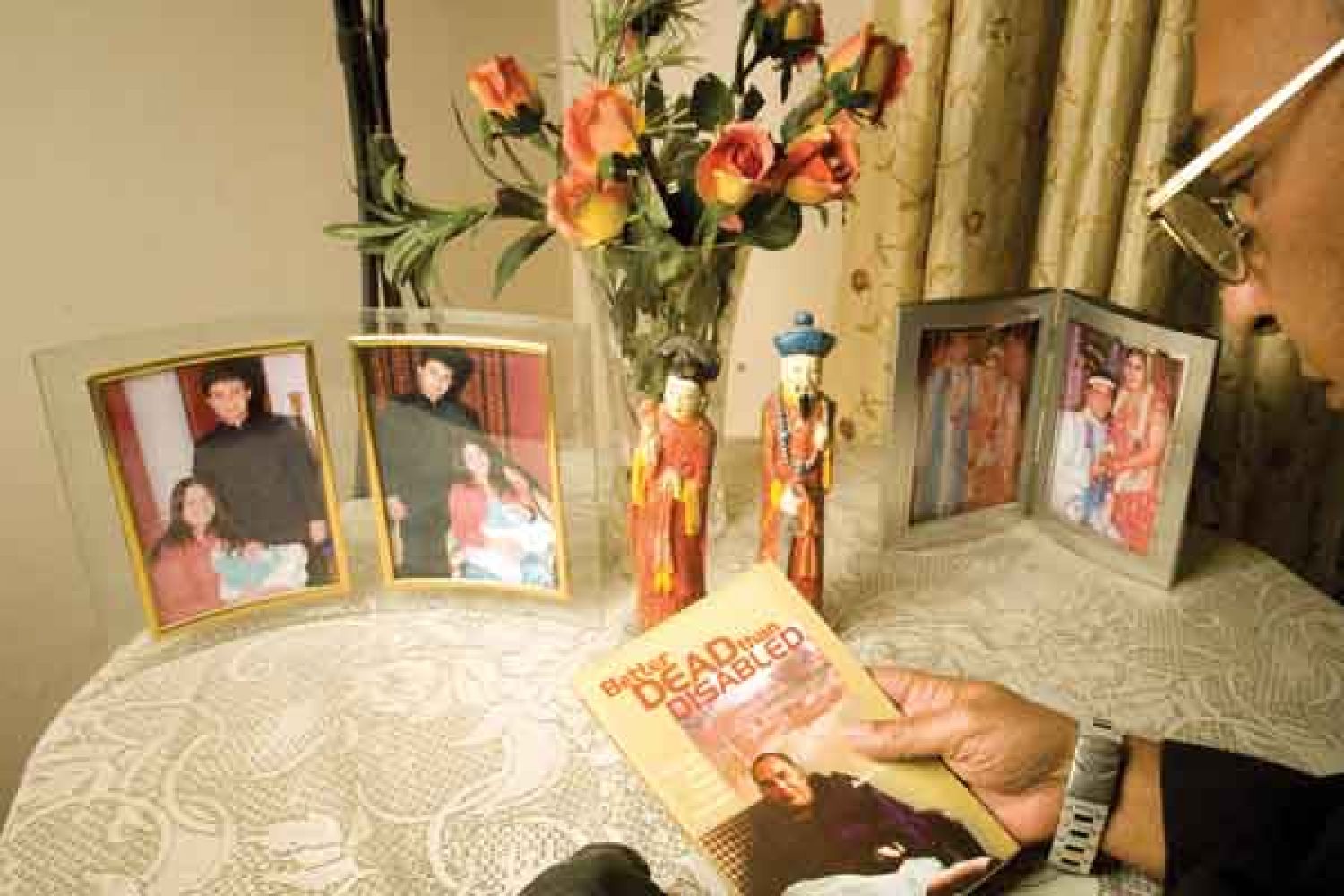

Colonel Anil Kaul, Vir

Chakra, has a striking personality. In retirement, his body has lost some of

its firmness, but behind his easy-going manner and charming smile is the steely

mentality of a soldier. The patch over his lost right eye and a black leather

casing on the stump of his left wrist add to his air of distinction.

Meeting him recently

at his ground floor flat in Gurgaon, Haryana, adjoining Delhi, was a pleasant

experience as usual, and an educative one. He makes incisive obser