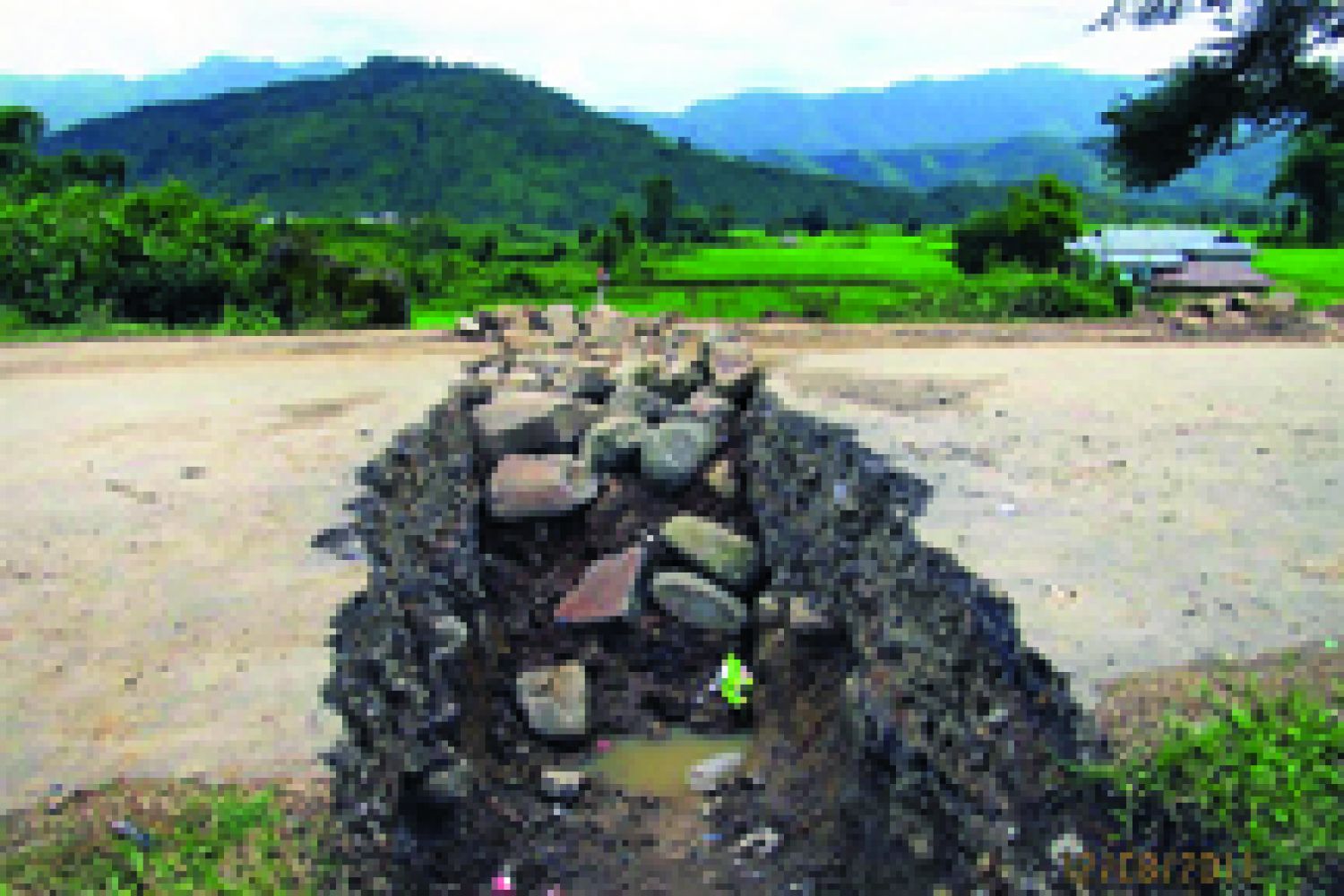

The road runs for 92

km in Manipur’s Senapati district, between and around the hills, and on an

ordinary day you cover it in three hours, a bit quicker if you’re more

adventurous. But for the hundreds of trucks, tankers and container lorries,

even 100 days have not been enough to cover this distance.

It’s no ordinary road,

this. It’s nothing less than the NH-39, the national highway, a strip of

battered asphalt that connects Imphal to Dimapur and Guwahati. It’s the route

throu