Living next to three chimneys of the Anpara Thermal Power Plant, 50-year-old Rajkumar Devi connects the dots that led her to her ills: “I got blood cancer right from the time the plant started coming up. I spend `9,000 for 30 tablets from PGI every month.”

The day starts for the government school beside her house with a thorough sweep and sprinkle, but the soot remains deep within the cracks of the floors. In summer, coal dust storms often turn day into night, even as teachers and children tie their scarves tightly around their faces while singing the national anthem.

With 10 power plants and 16 coal mines, the Singrauli-Sonbhadra (MP-UP border districts) region has been nicknamed the “Energy capital of India”. Understandably, it is high on the list of the country’s critically polluted areas. Jagat Narayan Viswakarma, a petitioner in the National Green Tribunal’s case in 2013 against the Union government for pollution in the area, estimates that about 500 deaths occur every year. Rarely, though, if ever, is death ascribed to heavy metal contamination.

Linking ailments to specific pollutants requires specialised testing. The few laboratories that should be equipped to conduct the tests, never end up releasing the results—either they actually don’t have the capacity to or they’re being persuaded not to let the results come out. Prof. G. D Agrawal of Banwasi Sewa Ashram

(The first Member-Secretary of Central Pollution Control Board.)

A forty-minute drive away from Anpara, Chilkadand village stands precariously at the edge of the Northern Coalfields open cast mine. During the monsoon, the dumps from the mine frequently spill into Chilkadand.

A study in 2012 by Delhi’s Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) confirmed that fluoride, mercury and arsenic were all higher than permissible limits in most water, soil and fish samples tested. It also revealed that over 84 per cent of the blood samples of the local population contained mercury above the safe level.

Look what my hands have become! When I come home after driving, I wash my hands repeatedly but within minutes, they’re the same. All of us who work in the mines cough constantly. Whatever I’m earning goes into medicines anyway. My future? When my body stops delivering, no company will keep us. Vimlesh Sawhney, 40, open-cast mine driver, Chilkadand.

“Burnt coal emits so much gas, sometimes it feels like my body itself will catch fire. When the dump spills into our cabin, the glass breaks and our heads get smashed. After some basic first-aid, the company just asks us to go. After sucking our blood, the company says go, you are of no use to us now.

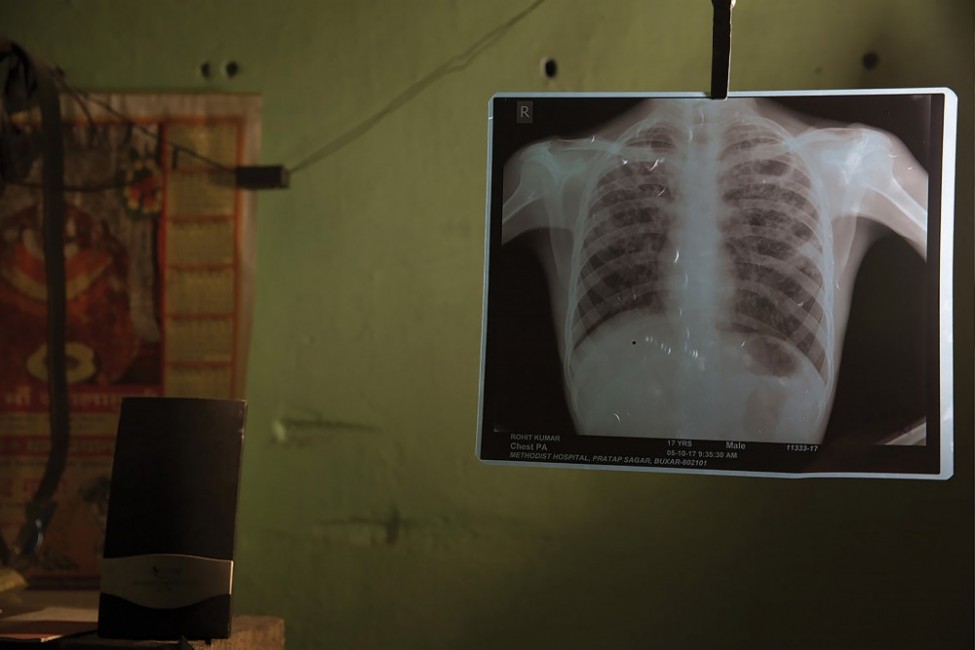

“My father died of tuberculosis in 2014. In 2015, I contracted it,” says 17-year-old Rohit Kumar who is living out his father’s destiny. In desperation, his mother Sukhraj Devi collected loose coal at night which she'd sell to pay for her husband's treatment. After his death, she travelled for Rohit’s treatment from Ashram, Badwahi and Renusagar to NTPC, Anpara and Buxar—but Rohit still remains bed-ridden.

Ash slurry from the Belvadah Ash pond, disposed of by NTPC Shaktinagar and Vidhyachal Thermal Power Plants, overflows into the Rihand dam. Even the committee constituted to look into the NGT case, chaired by A. B. Akolkar, Member Secretary of the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), shared its concern over the contamination of the Rihand river—the main water source there.

We realise that this is happening due to water —it is the fluoride polluting us. They tell us not to drink from the well, not to drink from the hand pump. So where should we drink water from? My whole family, our two kids have become handicapped. Our bodies have no life, no strength, no power at all. Laleram Yadav, Gariah, 10 km from Anpara Thermal Power Plant.

Gariya Block is located 10 km from Anpara. Records maintained by its Pradhan show at least 33 deaths registered in 2016 alone. The panchayat got samples tested at a recognised laboratory in Ahmedabad, and found that not a single water source was uncontaminated. This is accepted by the Jal Board too. Yet, the official cause of death of 22-year-old Raju from Bicchi Village of the same block was ‘an acute stomach ailment’.

During our time, there was no illness. In the last 10-15 years, it is everywhere. Those days, the water was not like this. Now, the water itself is the illness! My whole body has got jammed like iron. Only my hands move a little. How long can I live like this? Vindhyachal, a 70-year-old patient.

Ninety-five per cent of new power plant projects that have got the green signal don’t have treatment devices like flue gas desulphurisation and selective catalytic reduction units to limit pollution. In spite of a two-year notification, the deadline of December 7, 2017 set by the Supreme Court for thermal power plants across India to reduce emissions of PM, SO2 and NOx pollutants below specified limits has been missed. With a 66 per cent dependence on coal for power-generation plans, the government itself has appealed for a further extension till 2022.