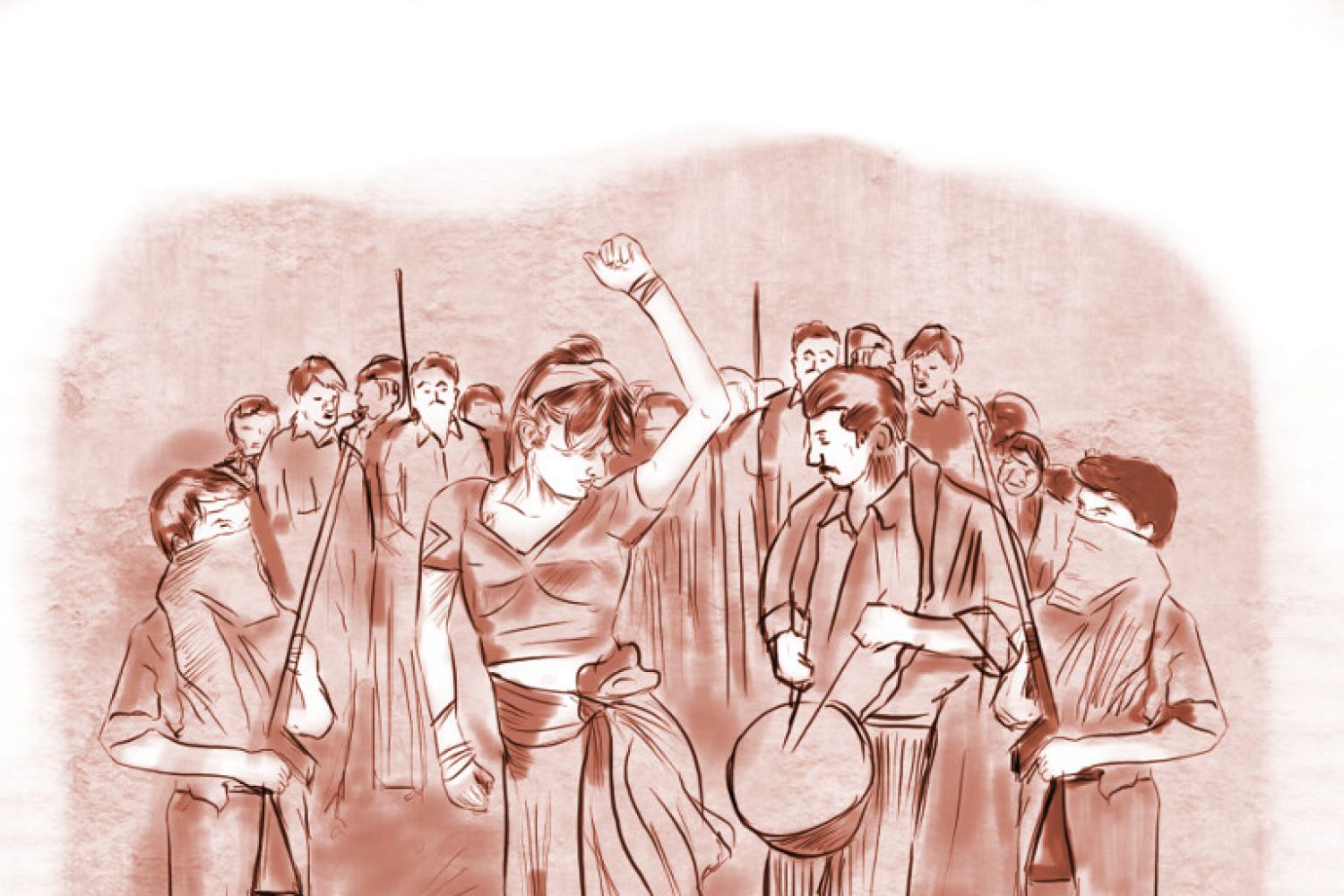

It’s a long-standing tradition in small town and rural cow

belt India. Few weddings or celebrations are considered complete without

night-long song-and-dance events. But it’s a practice that hides a world of

pain, shame and sexual violence. Yet its popularity continues to grow as more

and more families flaunt it as a sign of affluence and virile decadence.

“Sometimes it was good—when the men were not very violent.

But most often, the drivers would be drunk and abusive, hurting us,