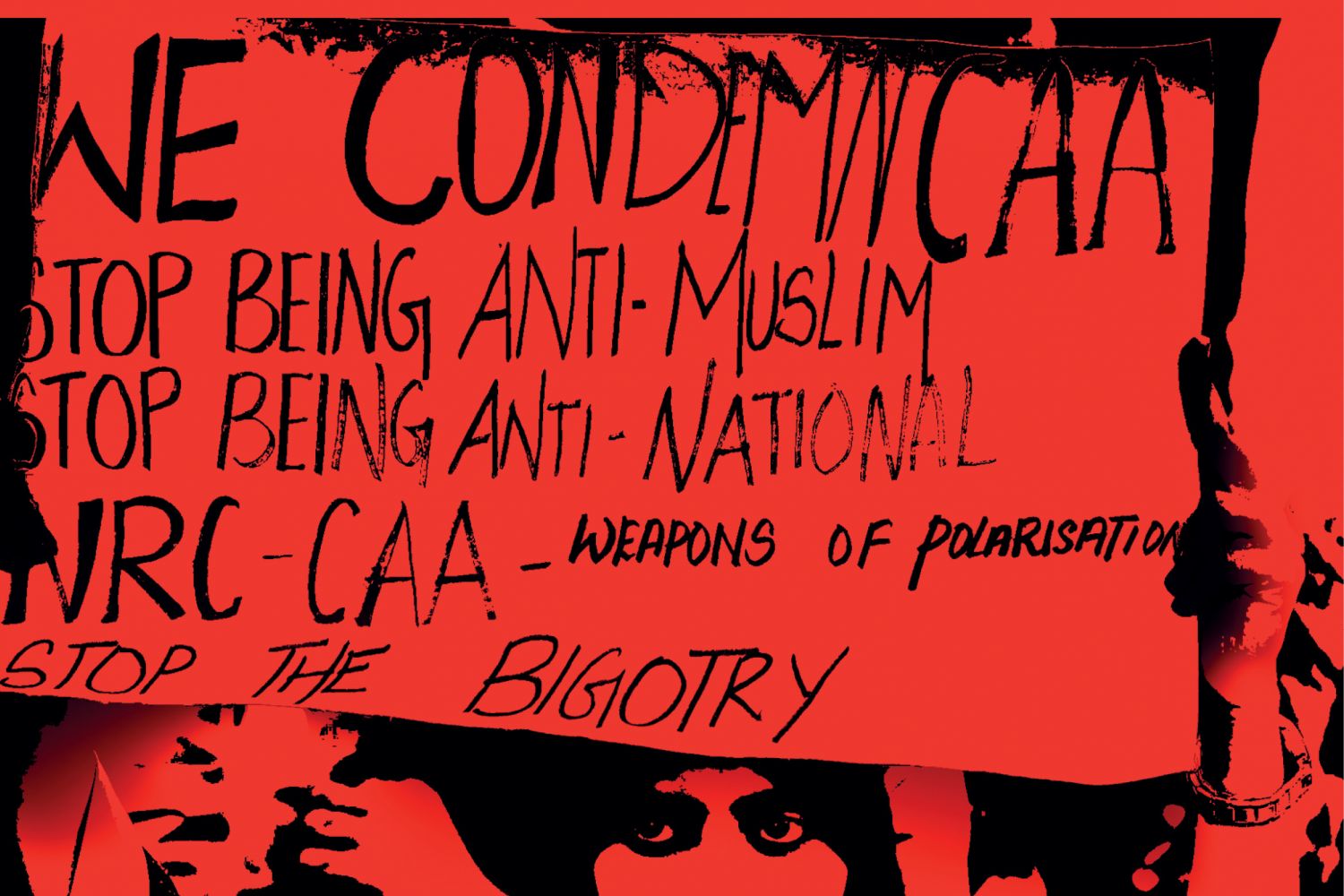

The Indian state’s violent response to the nationwide

protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act is a pointer to the fact that

the country is in the grip of an undeclared emergency. Despite its

discriminatory nature this aggression has fostered an ecosystem that offers

space for apologetic justifications that sanction its moral legitimacy.

Trying to make sense of this law as a charade by the

government to mask the failure of its economic policy or as one more attempt to

polar