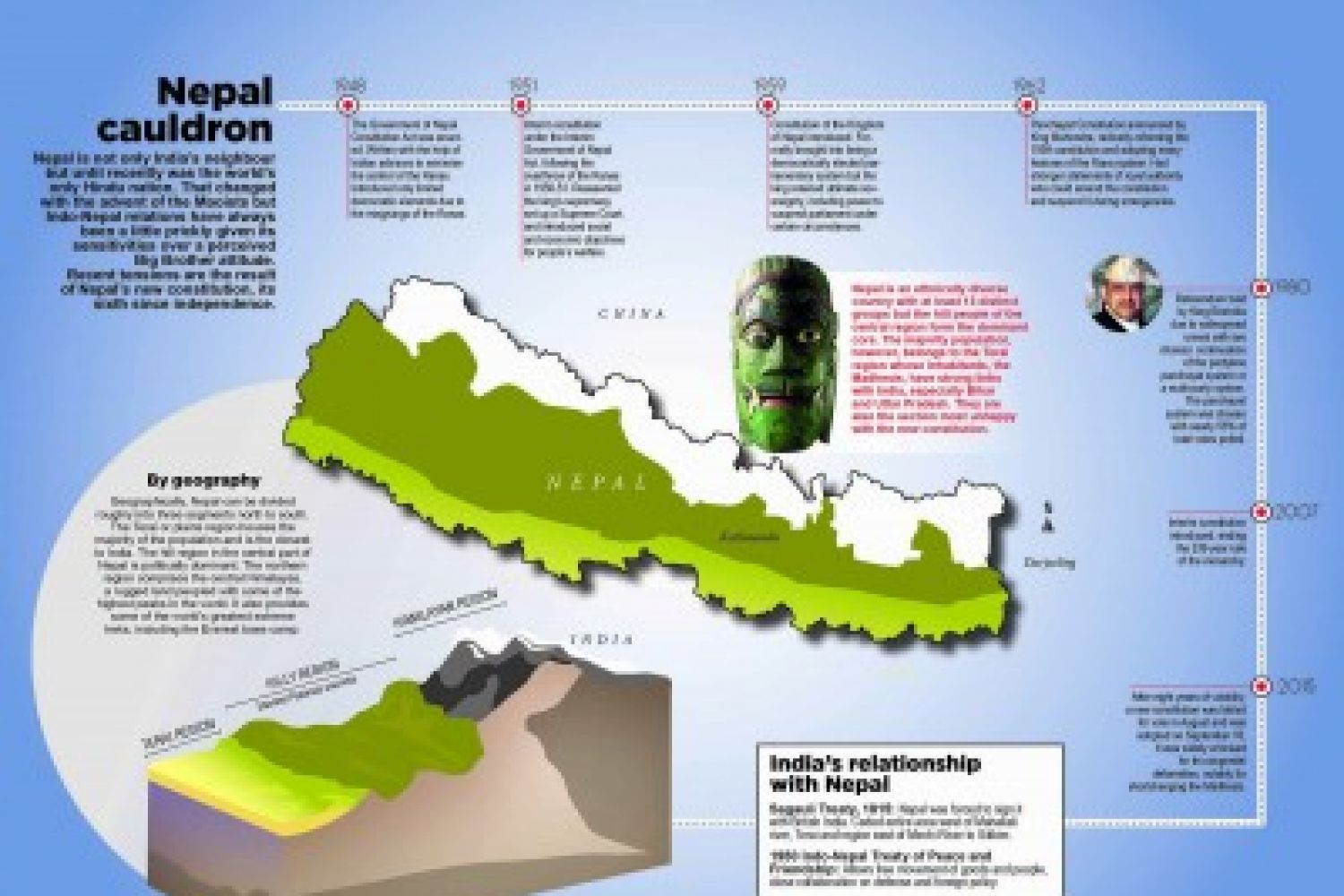

Situated on the southern slopes of the Himalayas, landlocked

Nepal’s 3,222-kilometre frontier is sandwiched between two Asian giants—India

and China—its only neighbours. Surrounded by the Tibet Autonomous Region of

China in the north and Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal and Sikkim on the

other three sides, Nepal’s economy is at the mercy of India and to a lesser degree China.

Projected as a buffer state between India and China,

everything conspires against its rise and stability