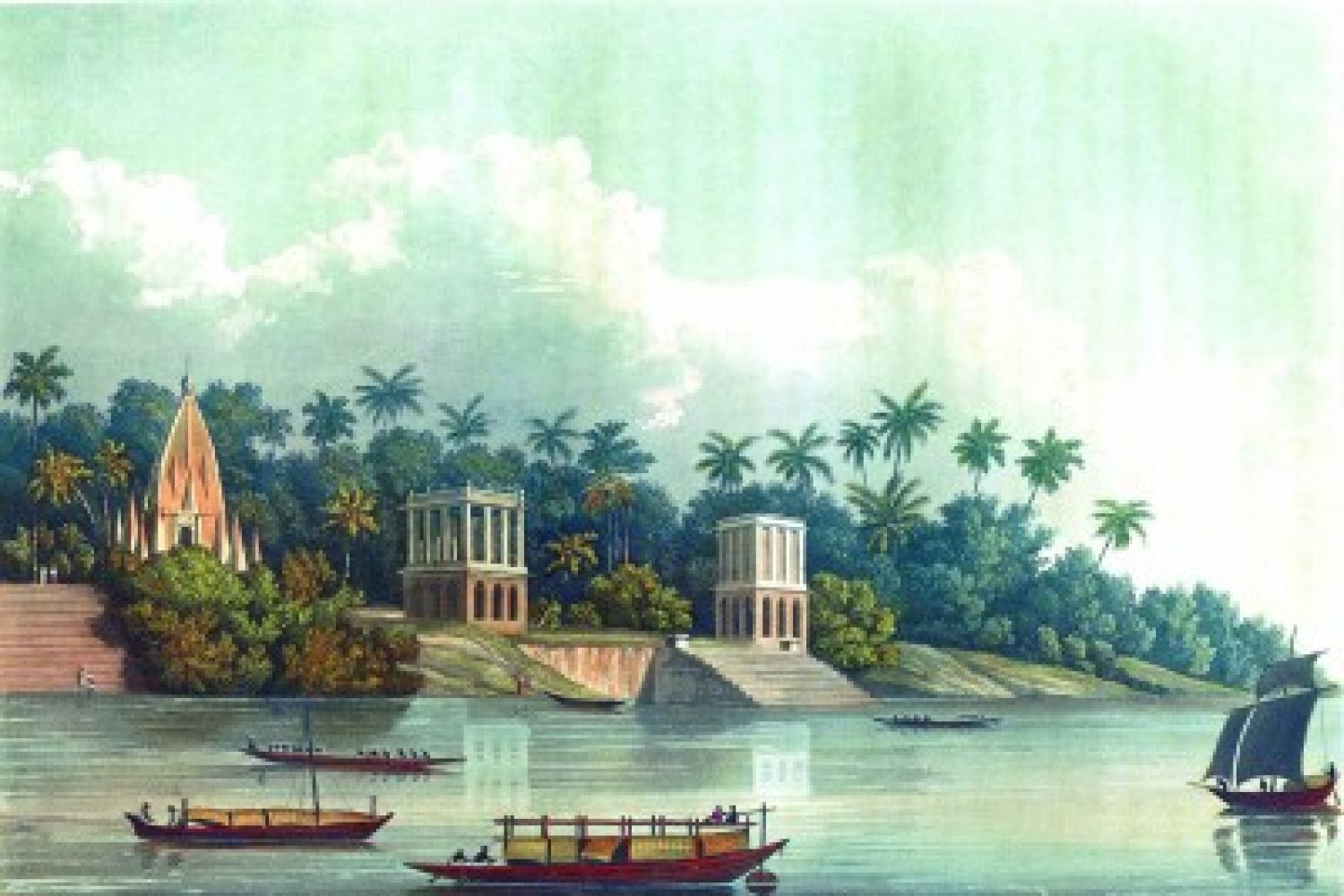

Calcutta, the capital not only of Bengal but of all India,

being the seat of government and residence of the governor-general and council,

has been so much talked of, and so often described, that nothing new or

interesting concerning it can be offered to the reader. A traveller, therefore,

who visits Bengal from curiosity and a desire to explore its grander and wilder

beauties, will not long tarry in its metropolis, but, deciding on the mode in

which he will travel, make his preparations ac

Continue reading “A picturesque tour along the Ganges”

Read this story with a subscription.