India’s

strength, endurance and indeed place in the world are on trial as never before

in its 70-year history since Independence. At the forefront of a changing

paradigm the grand strategy is to consistently challenge historical archetypes.

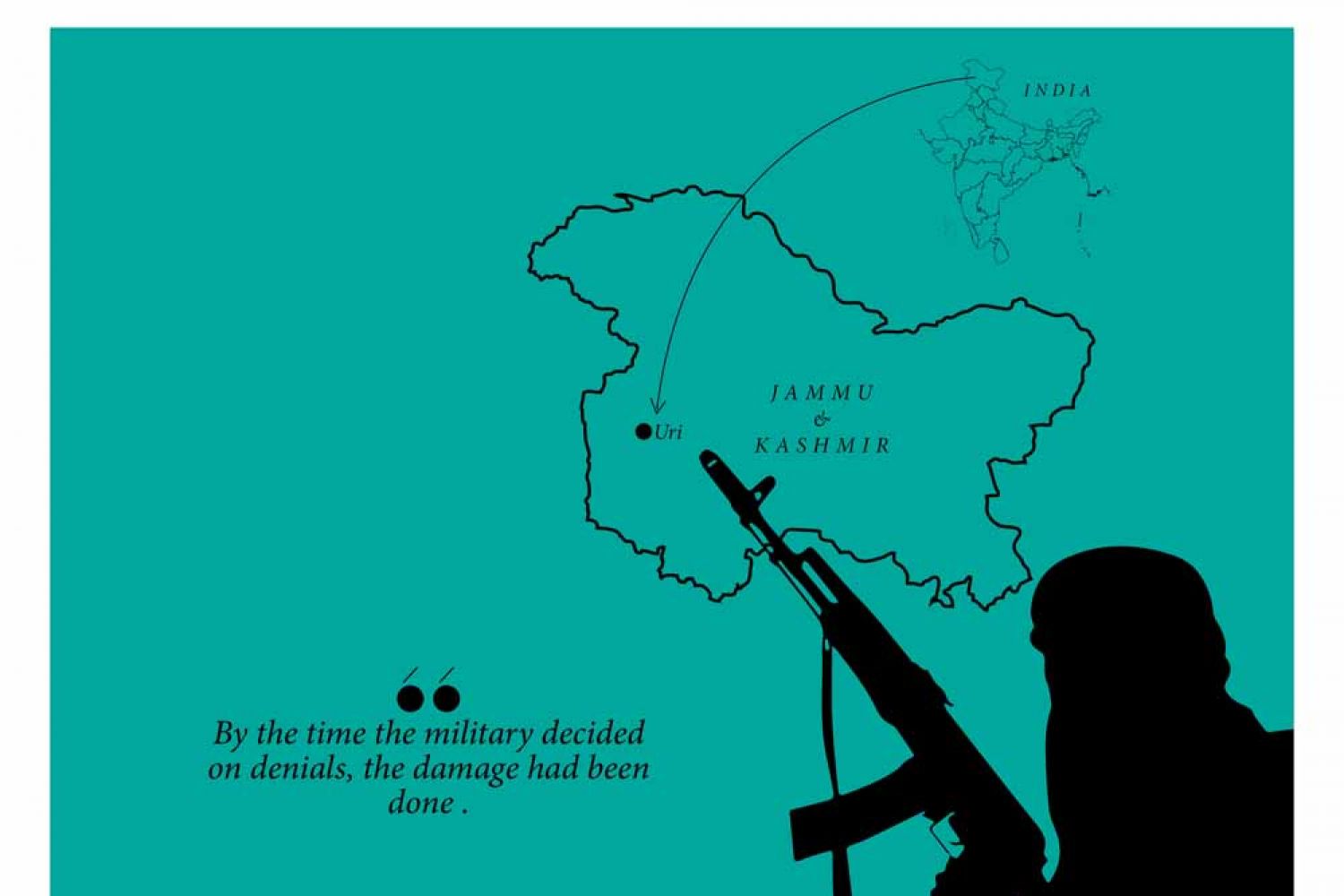

The reaction to the January 2016 Pathankot air base attack, for instance, was

“strategic-restraint-laden” in the old tradition. But the assault on the army

base camp at Uri in September 2016 provoked a very different response.

Throwing

old-sty

Continue reading “Changing track in changing times”

Read this story with a subscription.