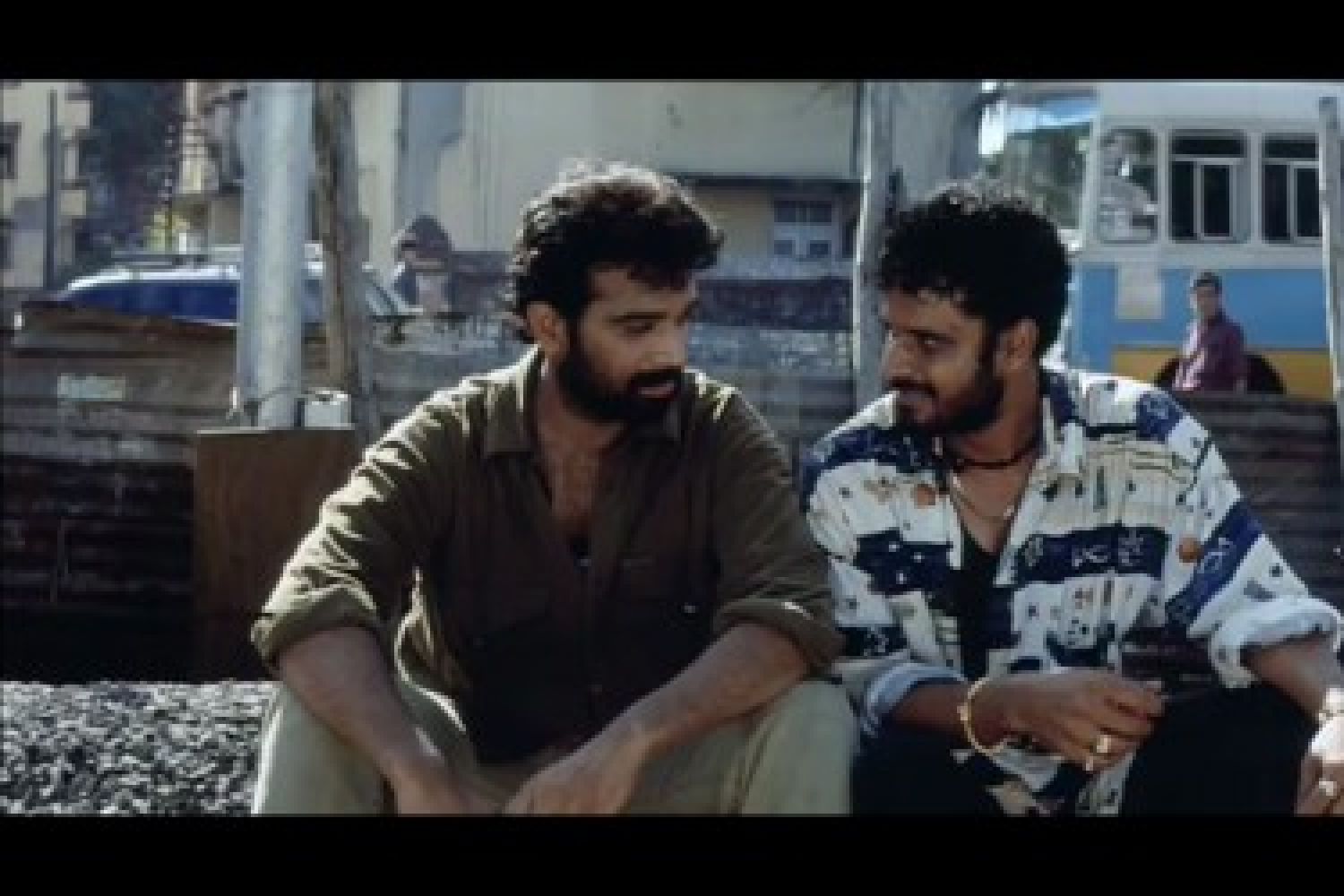

At the beginning

of Gangs of Wasseypur 1, Shahid Khan (played by Jaideep Ahlawat)

beats a muscleman to death in a coal-mine, blaming him for the death of his

wife. The muscleman had kept Shahid’s friend waiting when he’d come with news

that Shahid’s wife was facing complications during childbirth. Eventually,

Shahid makes it home, but his wife is dead, leaving behind a child who

eventually grows up to be Sardar Khan (Manoj Bajpai). In the fight sequence

that follows, where Shahi