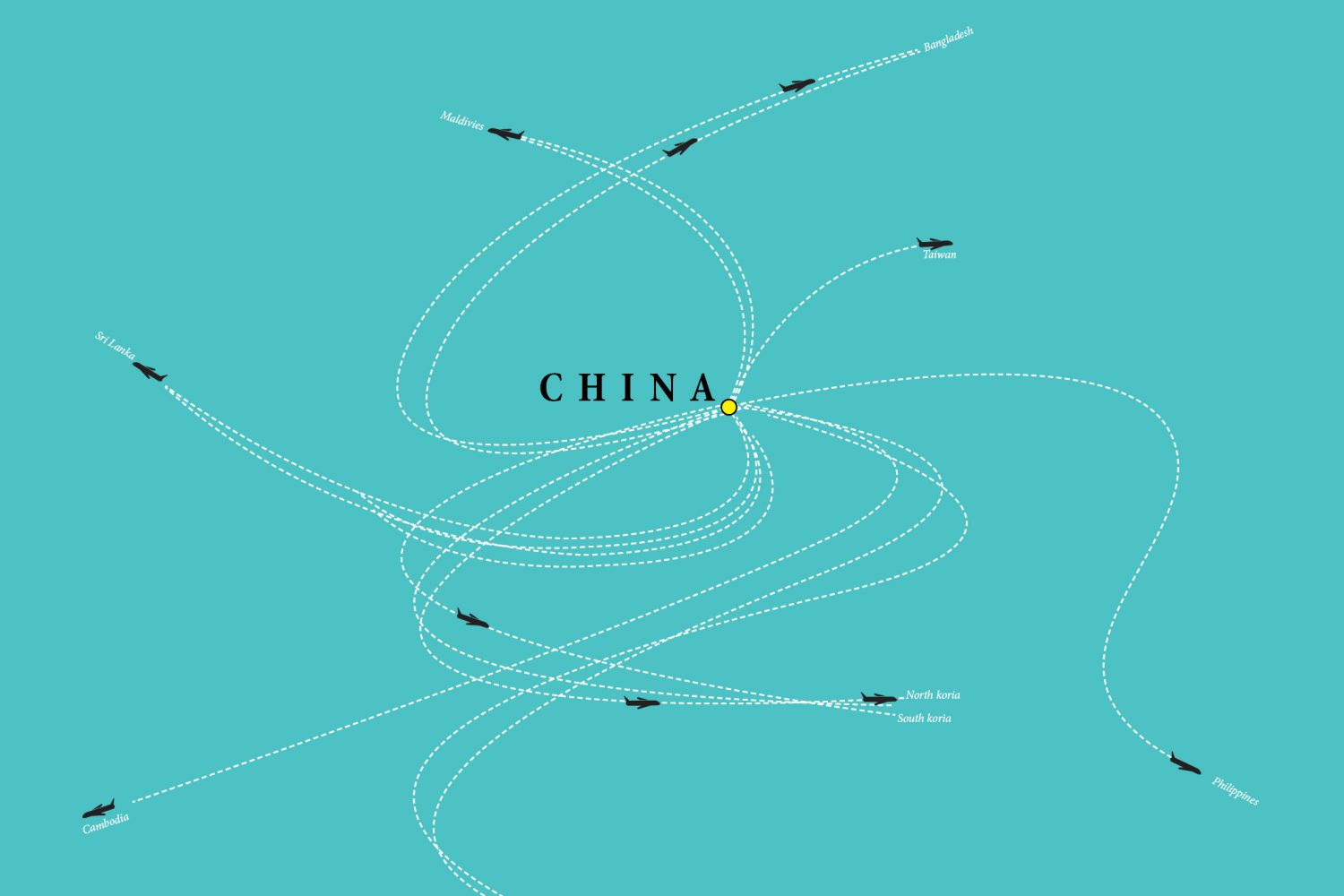

Obsessed with international recognition, winning friends and

outwitting adversaries, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has followed a baffling

global itinerary and travelled to 53 countries covering five continents during

his 46 months in office. Claiming to propel the economy and burnis India’s

reputation, Modi has travelled five times to the US, three times each to China,

Russia, France and Germany and twice to 10 other countries, besides 38 maiden

visits to as many countries. Signing a plet