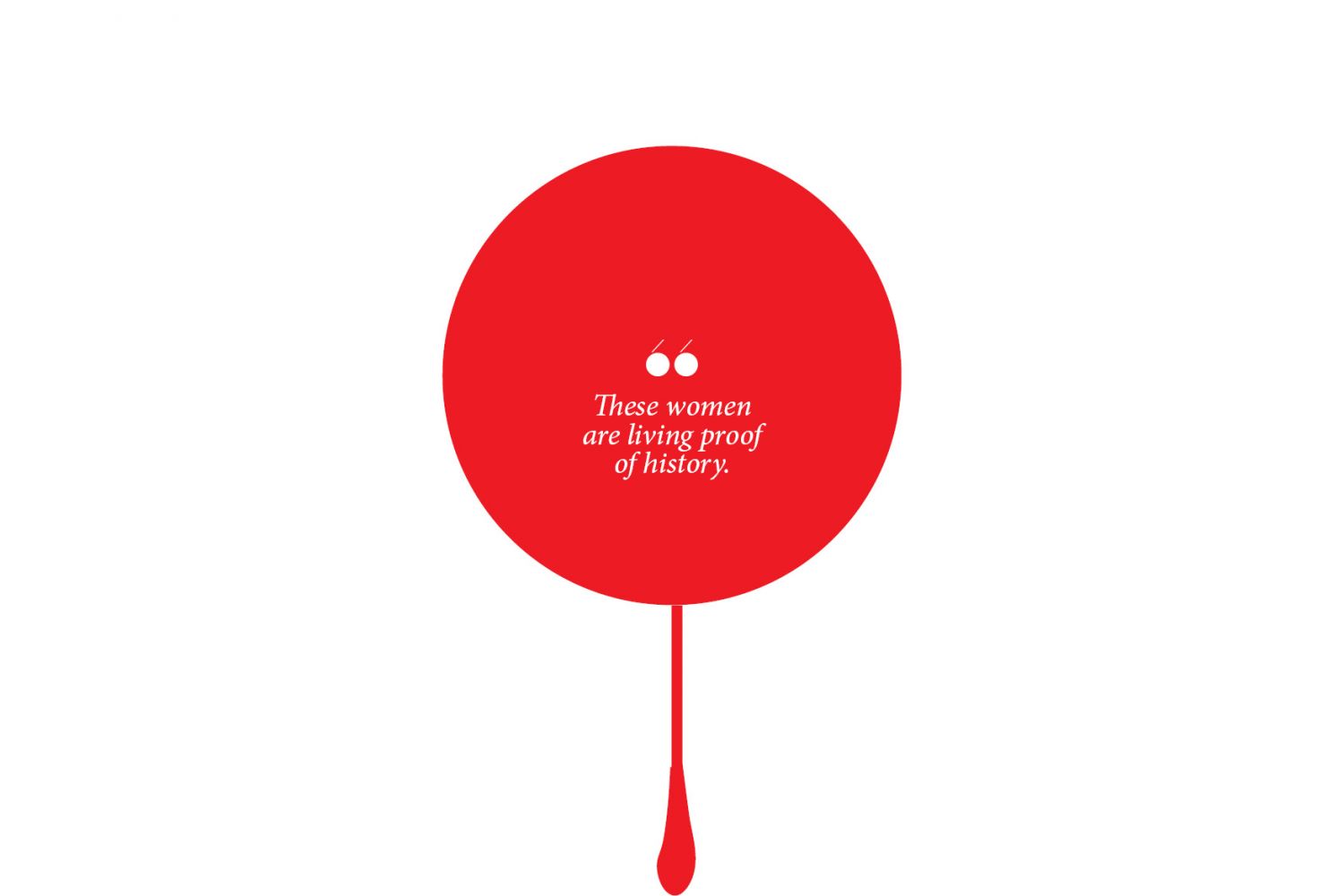

One morning in January 1992, long before the #MeToo movement

was even an idea, a group of South Korean women gathered outside the Japanese

embassy in Seoul, shouting things such as “apologise” and “shame on you”. It

had taken them more than 40 years to break their silence and stand up against

the sexual slavery they had endured as Japan’s so-called comfort women before

and during World War II. Twenty-six years later, a handful of the surviving

victims, along with their supporters,

Continue reading “Japan writes out its war crimes from history”

Read this story with a subscription.