“Many shall run to

and froAnd knowledge shall

be increased” (Daniel,12 : 4)- The Old Testament

1611“Many will be at

their wit’s endAnd punishment will

be heavy” (Daniel, 12: 4)-The Old Testament

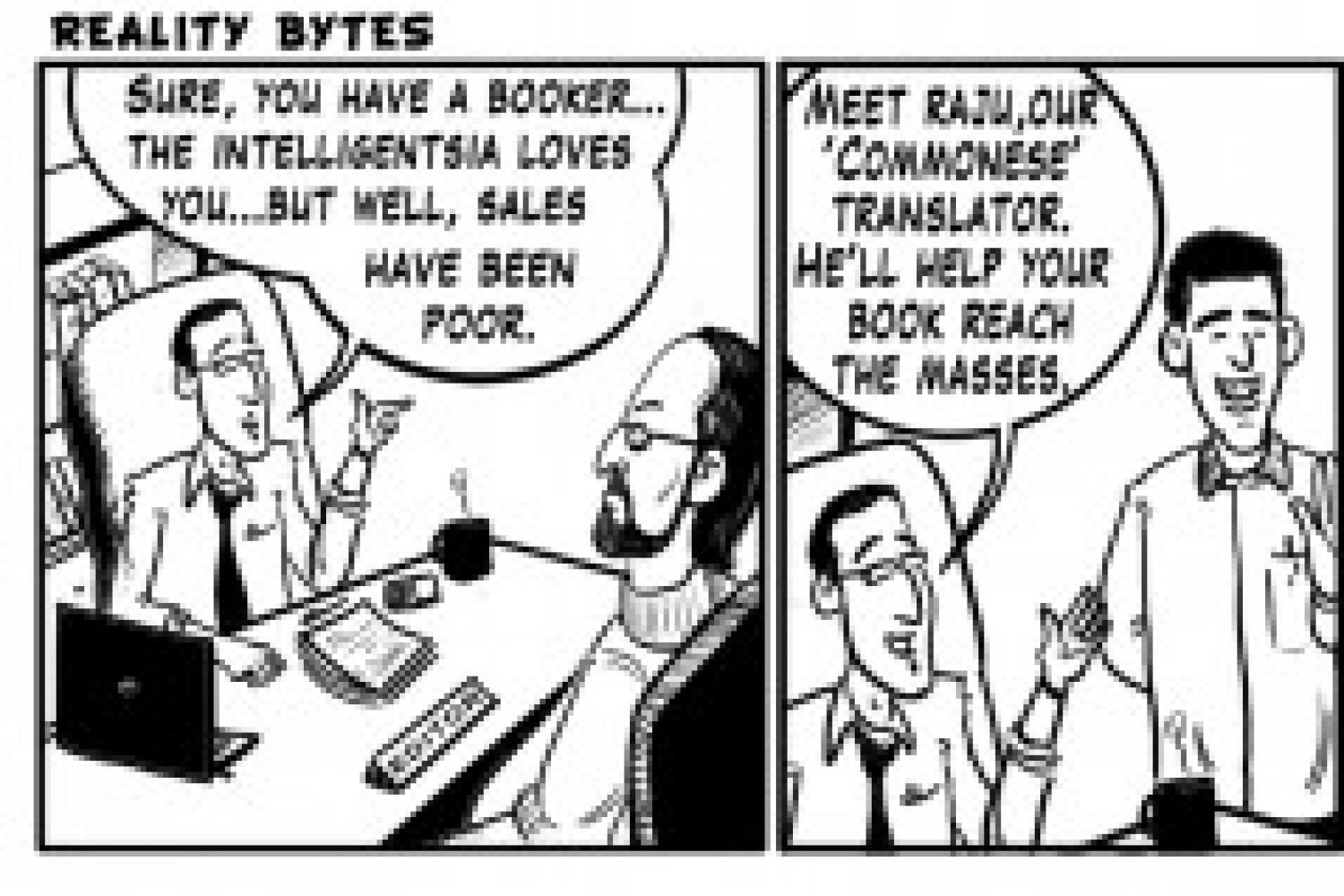

1970Every time someone

asks me to write or speak about translation I panic and read about a thousand

pages on the subject and come up with nearly the same ideas as before and

perhaps a few new quotations. But now I’m wondering whether to Uncle Sam or

John Bull it because being