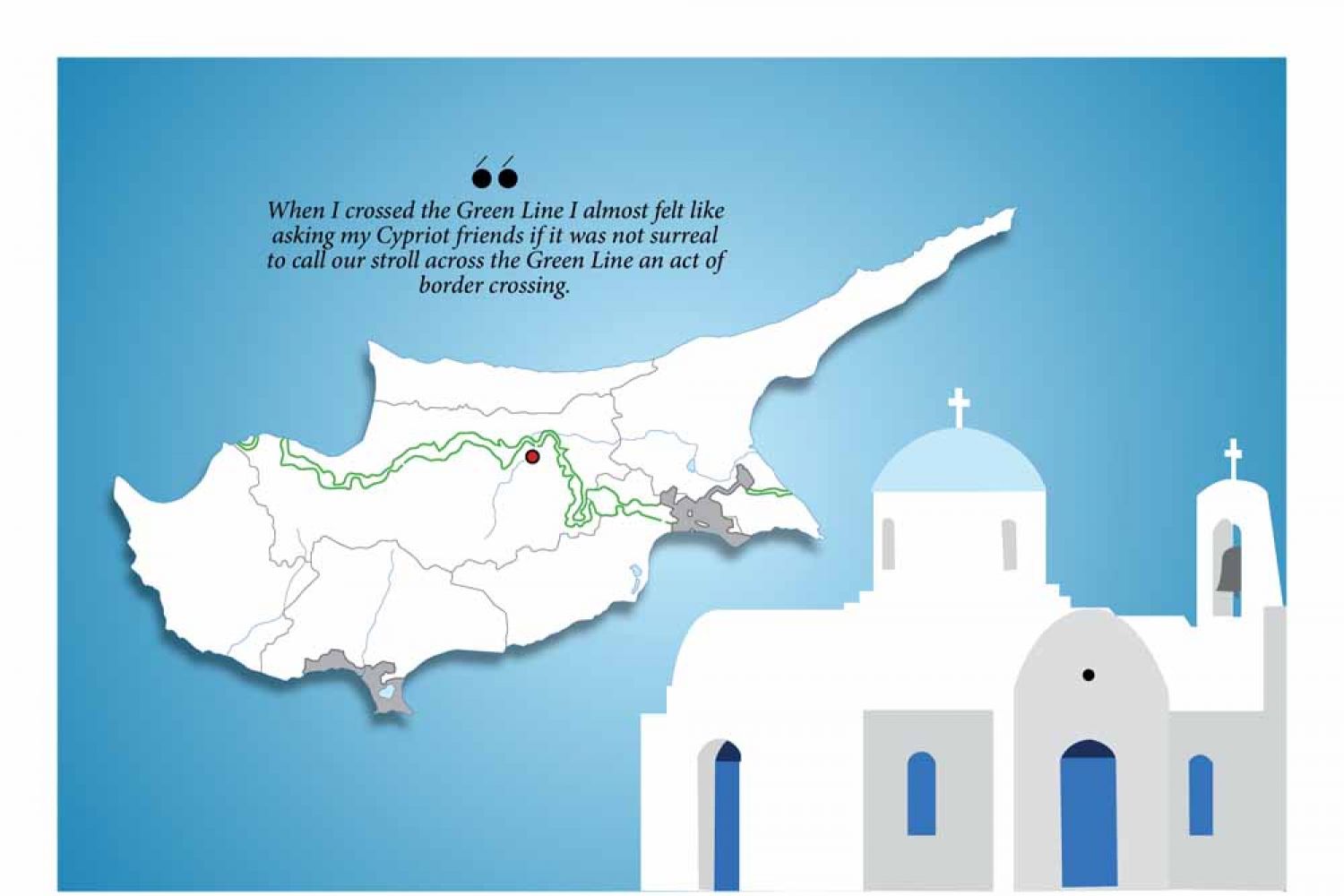

An Emirates

flight from Dubai brought me to Larnaca on a hot summer afternoon. It is a

small port city on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, inhabitated by 50,000

people, but with a history that stretches back to 13th century BC when it was a

city state named Kition, home to the philosopher Zeno, founder of the Stoic

school of philosophy. In the 3rd century BC, Zeno lectured his students on apatheia

or equanimity. For the master, wisdom was earned by reining in one’s desires

and emotion