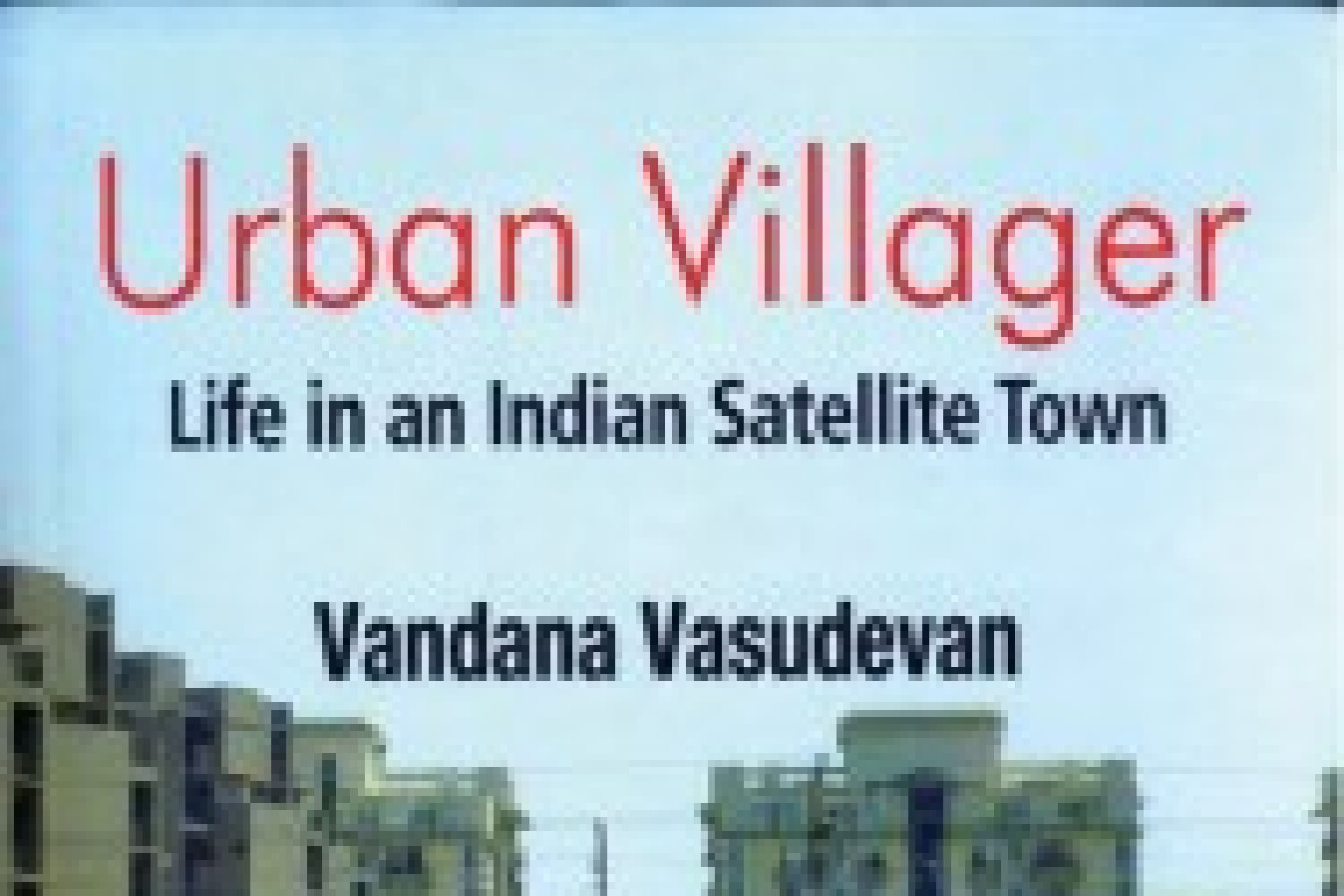

Expecting that the

metro will improve connectivity to Greater Noida, all the prominent builders of

NCR have a finger in the Greater Noida pie, except DLF, Gurgaon’s monarch.

Ansals, Unitech, Supertech, Amrapali ATS, Eldeco and Parsvanath are all

developing large residential projects in Noida and Greater Noida. Everyone has

built or is building a gated community with high rises, low rises and in some

cases villas, which allow the pleasures of a bungalow but with the facilities

of a buildi