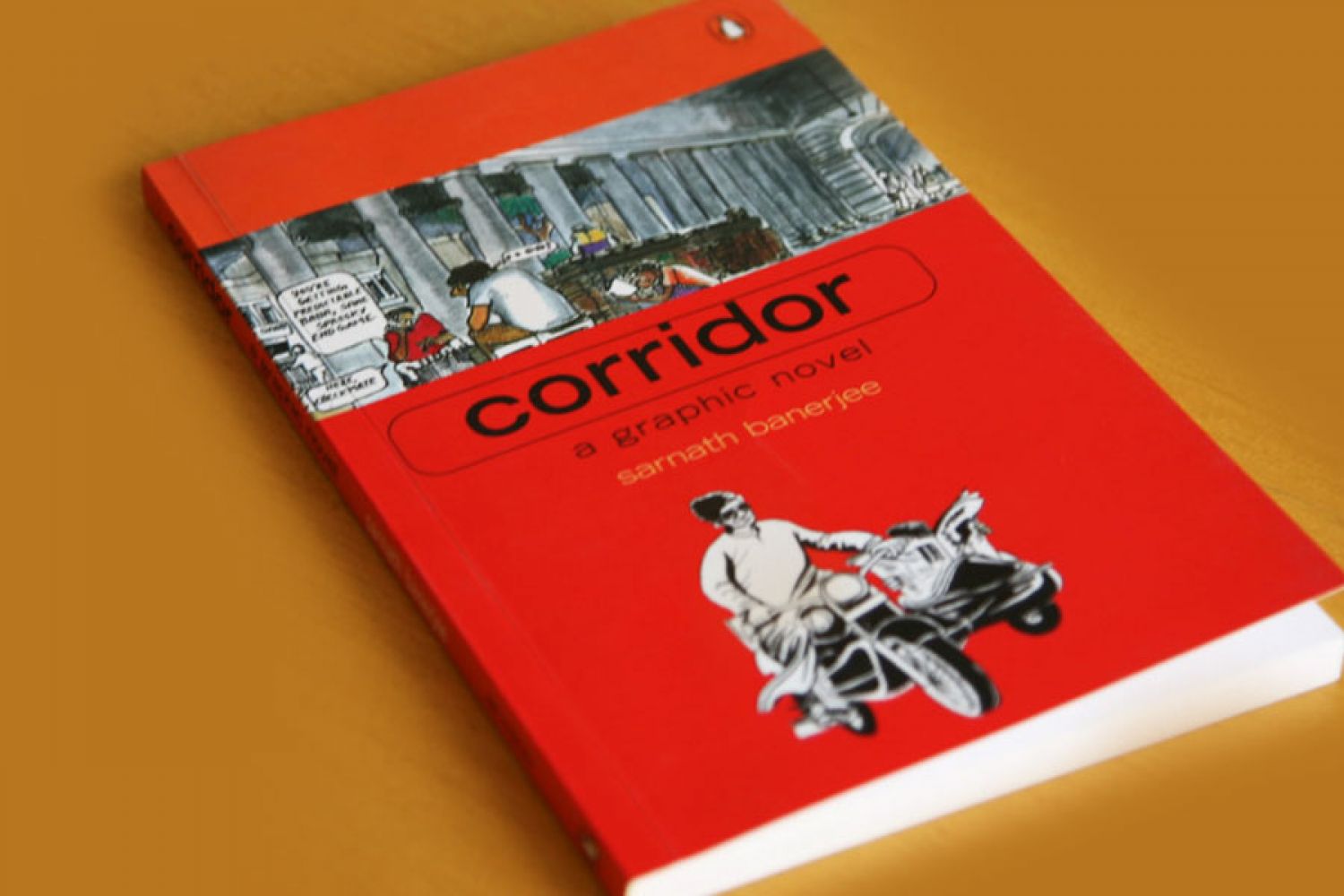

If one were to go by

the 14,000-strong crowd that thronged the two-day comic convention in Mumbai in

October, the future of the Indian graphic novel is bright and promising.

Excited by the response their stall received, Kishore Mohan of Libera Artisti,

a Thiruvananthapuram based three-man artist combine who are into the final

production stages of their mini comic series Auto Pilot, said: “If we are able to sell to even one-quarter of

the people who visited us at the convention, we’ll ha