When everyone

either returnsOr goes away to go astray,A prohibited personComes out of her selfAnd waits to sayThat the greenWhich flowers and swaysOn hilltops and sea-slopesAre the valleys inside my self;That it’s through my selfThe trains climb the hillsSeekingThe shadow-complaints of winter.

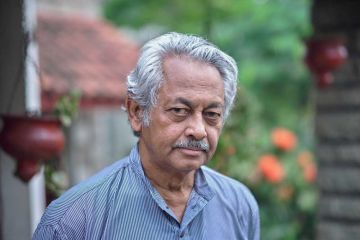

-Latheesh Mohan(Who will write the travelogues of hilltops?)

An unapologetic

sensual stylist and an even more unapologetic campaigner of a set of

ideals that is at odds with the domineeri