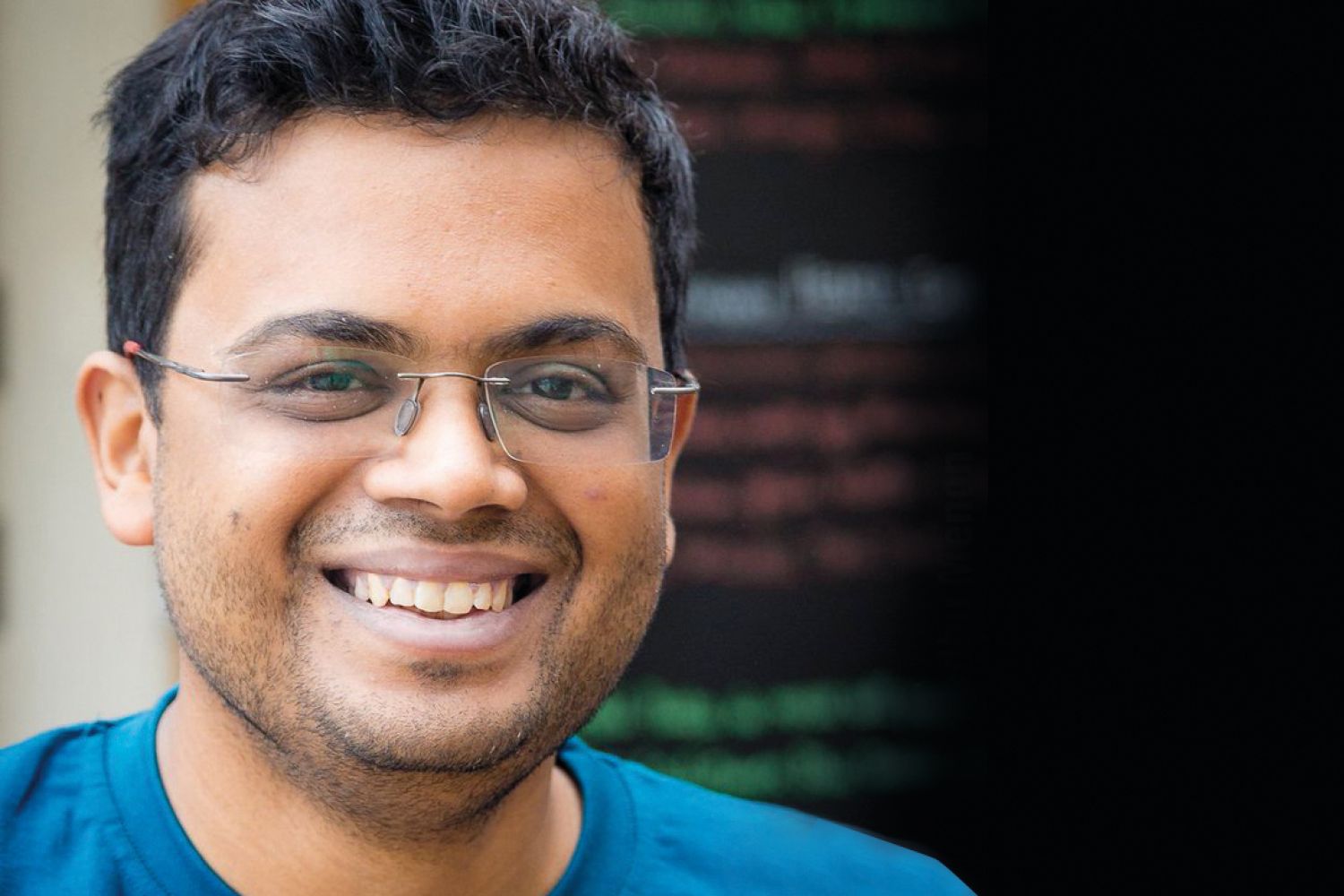

Kiran Jonnalagadda is the co-founder of HasGeek, a startup in

Bangalore that organises technology conferences and hangouts for like-minded

hackers. In 2015, Kiran was one of the movers behind the Save Internet

Campaign, which succeeded in mobilising one of India’s biggest online protests

for net neutrality.

The campaign succeeded in getting the Telecom Regulatory

Authority of India (TRAI) to recommend against differential pricing for

Over-the-Top-services and Facebook’s Free Basics.