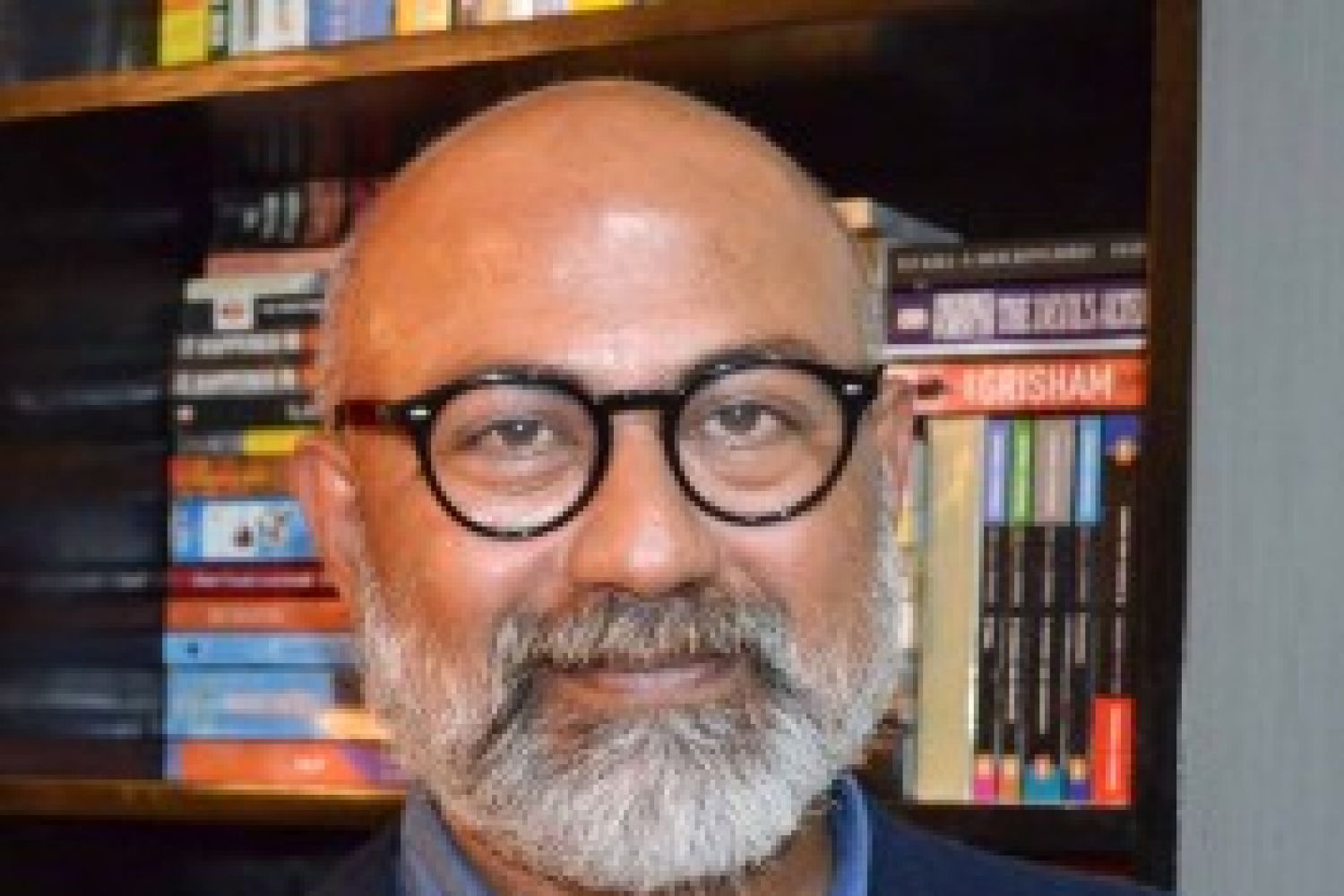

What began for journalist Akshaya Mukul as a conversation

with his father in 2008 ended in a 500-page volume that has won awards and

raised eyebrows in equal measure. His book on Gita Press was intended to be the

chronicle of a little printing press that became a force in the world of

religious publishing. It became Gita Press and the Making of Hindu India,

winner of the Shakti Bhatt First Book Award, the Crossword Book Award, Tata

Literature Live! Book of the Year Award, and the Atta Galat