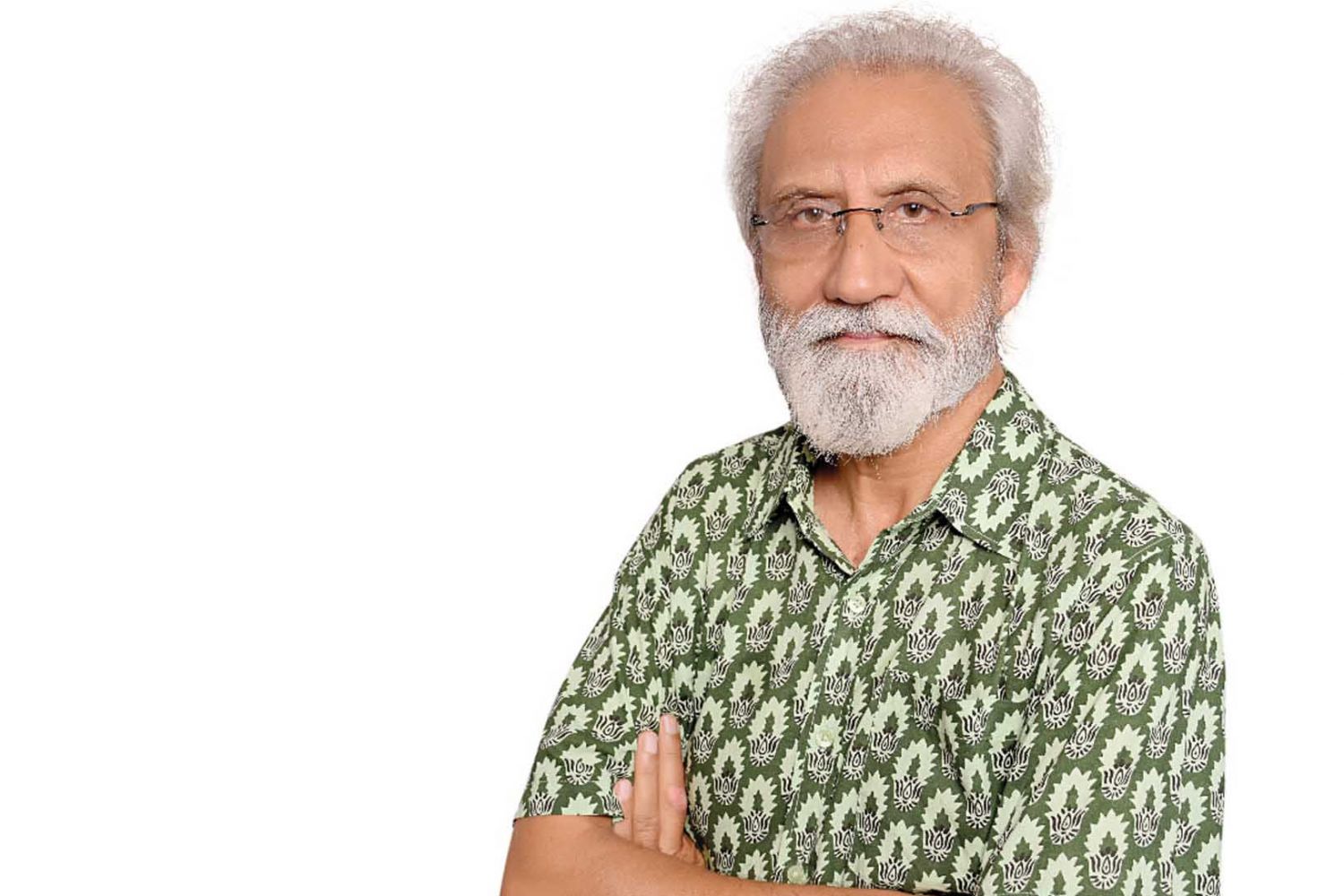

S.Irfan Habib is a historian of modern India and a public intellectual. He has worked as a historian of science, particularly in India. His interest in Bhagat Singh goes back to 1974 when he chanced upon an article on him by Prof. Bipan Chandra. Habib has delved deep into the life of Bhagat Singh as a revolutionary ideologue of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association. His book, To Make the Deaf Hear: Ideology and Programme of Bhagat Singh and his Comrades, focuses on the political phi