Since the

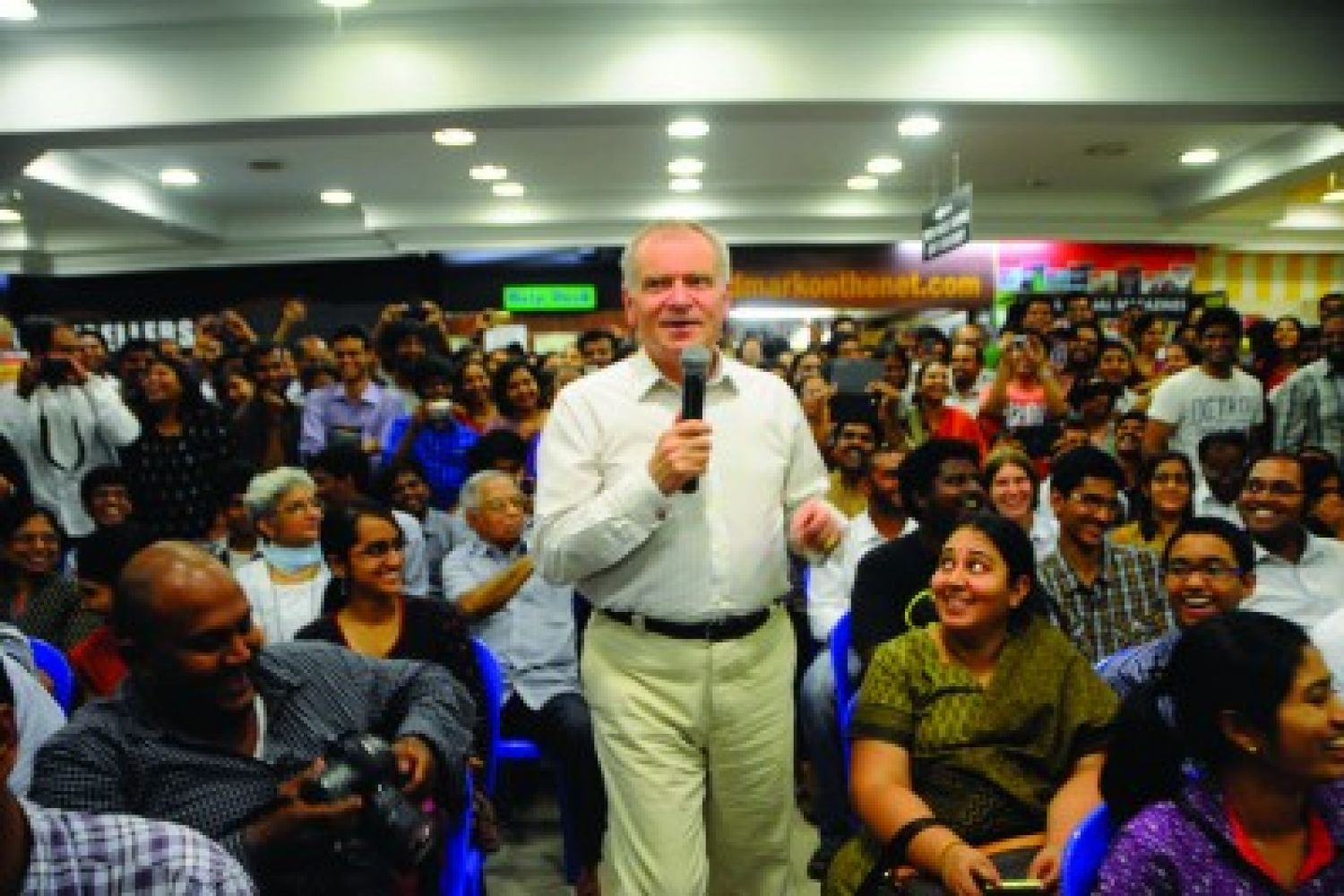

commencement of Jeffrey Archer’s India tour, Landmark bookstores across the

country have been flooded with seekers of autographs and advice. When he makes

his entry at a Chennai outlet, complete with cricket-ball cufflinks, Archer is

in top form. “I have an announcement to make, and it would be nice to make it

on a serious occasion like this. I want to say how absolutely delighted I was,

how proud I was, and how pleased I was... that England defeated you so easily.

And how eq

Continue reading “Raising Kane and fighting piracy”

Read this story with a subscription.