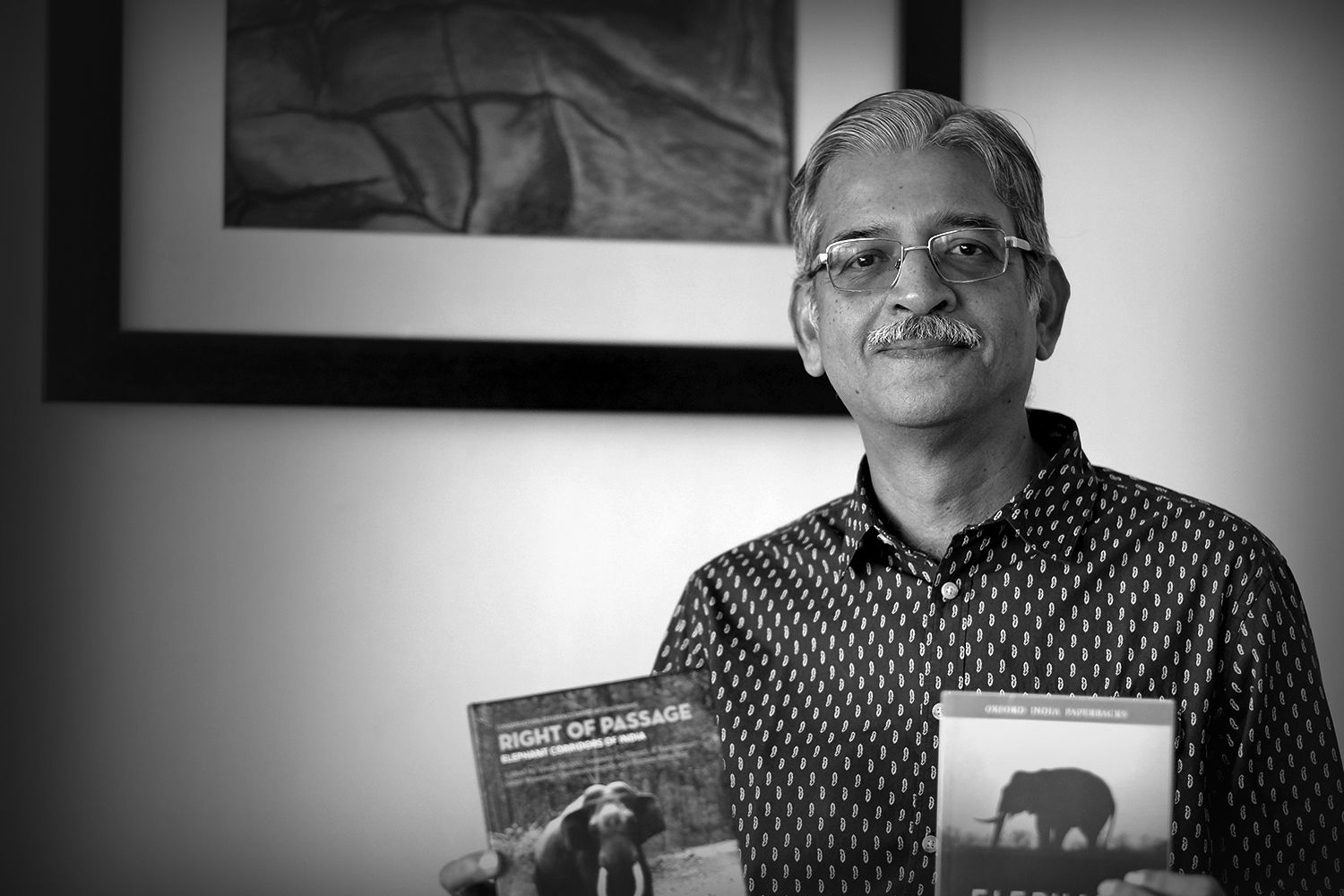

Raman Sukumar—the man

who knows more about the Asian elephant than anyone else in the world, chanced

upon his passion by accident. In a conversation with the Indian ecologist

Madhav Gadgil, who was his PhD supervisor, the latter told Raman about a few

skirmishes involving elephants in a few villages on the outskirts of Bengaluru.

“I just took that idea and kind of ran with it,” he says.

Sukumar today is known

as foremost expert on the ecology of the Asian elephant and human-wildli