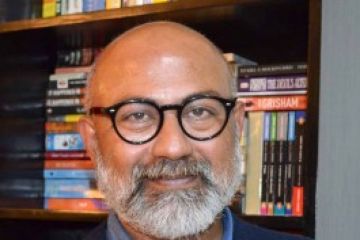

Judhajit Sarkar, an Indie filmmaker with an abiding love of

cinema has made two films in the last three years, namely Khashi Katha

(“The Tale of a Castrated Goat”) and Kolkatar King (“The King of

Kolkata”). They are both gripping and are made on very small budgets; of under

a crore of rupees. The treatment in both films has zest and humour despite the

unshakably dark content, a far cry from mainstream films attempting a ‘serious’

subject. There is no sop on offer at the end of a

Continue reading “‘With Shah Rukh and IPL we don’t stand a chance’”

Read this story with a subscription.