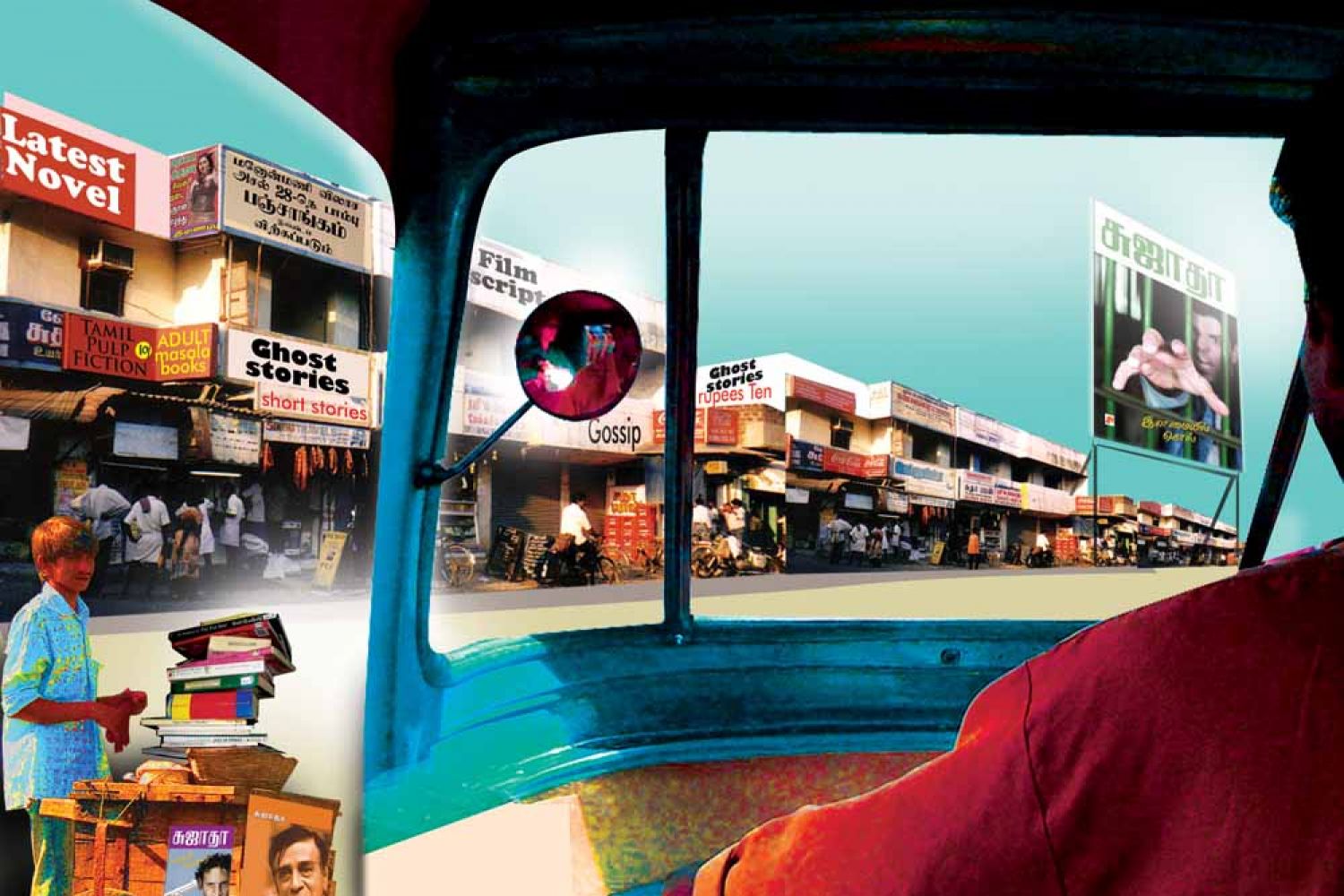

���Have you ever slept

by the roadside? As a youngster I often spread a mat on my street and lay on my

back.” That’s hard to believe when you see S Ramakrishnan at work in his

compact flat, updating his website while his wife fondly checks his literary

awards for imaginary specks of dust.

But the 45-year-old

writer from Virudhunagar is matter-of-fact about it. “I came to Chennai 25

years ago, and from the swankiest apartments to the most unimaginable living

conditions, I’ve seen