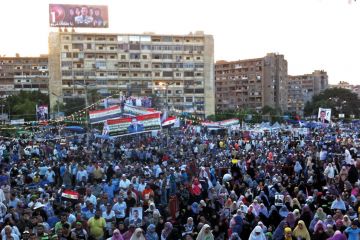

Every day around

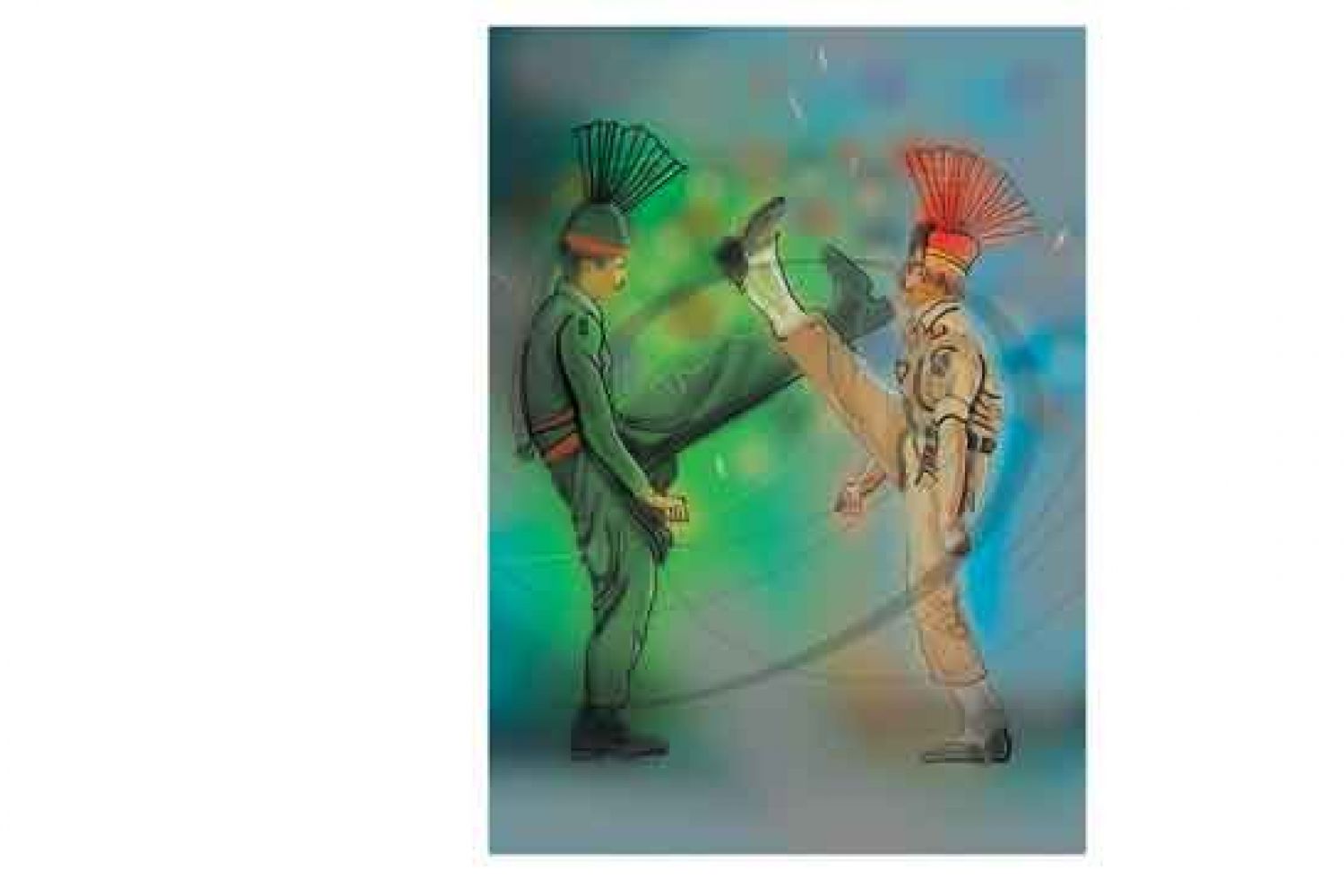

sunset, on the outskirts of Lahore, at the Wagah border between India and

Pakistan, the public gathers to see a show of military muscle and colour in a

ceremony that dates back to 1959.

People from all walks

of life become part of the message to the other side. They hold posters

expressing solidarity with Kashmir, as loudspeakers blare patriotic songs.

There’s also a recorded recitation of Quranic verses that focuses on

non-believers.

The road from Pakistan

goes u