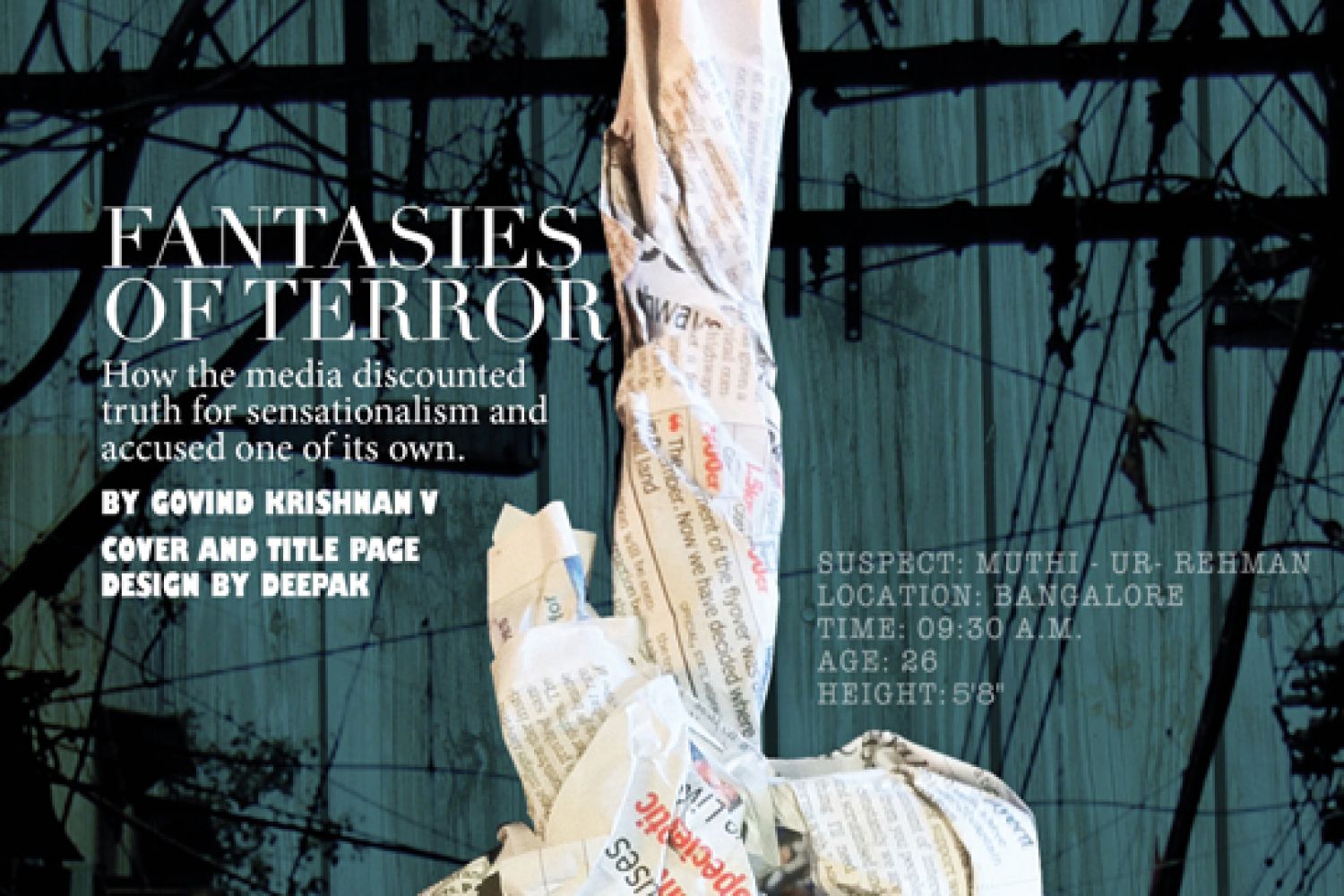

On August 31, 2012,

the Deccan Herald carried this story on its front page:

“The Central Crime

Branch (CCB) of the City police on Wednesday cracked down on alleged terror

modules in the State, arresting 11 people including six from Bangalore and five

from Hubli. The 11 men were held for their alleged links with banned terror

organisations, Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT) and Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HuJI), from

across the border. L. R. Pachau, Director General & Inspector General of

Polic