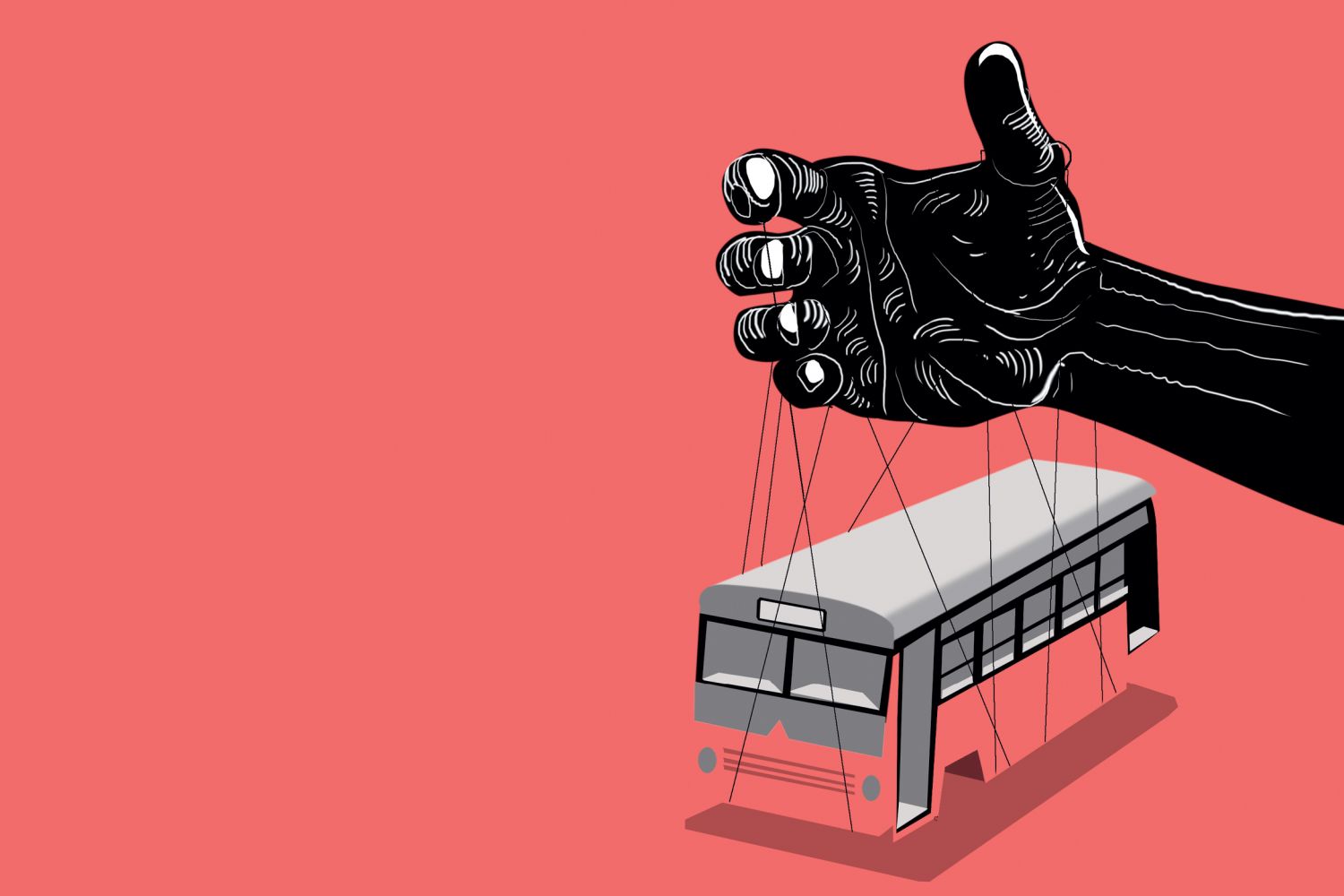

The one-kilometre ghat road bus journey ended in injuries and death. On September 11, a Telangana State Road Transport Corporation (TSRTC) bus coming downhill from Kondagattu temple in Jagtial district careened out of the road and fell into a gorge, killing 58 people and injuring 43.For about 30 years, the bus’ regular route and schedule was the start in Jagtial for a 30-km journey to Shanivarampeta, make three trips to and fro, halt at night in Shanivarampeta, and make two trips to and fro the