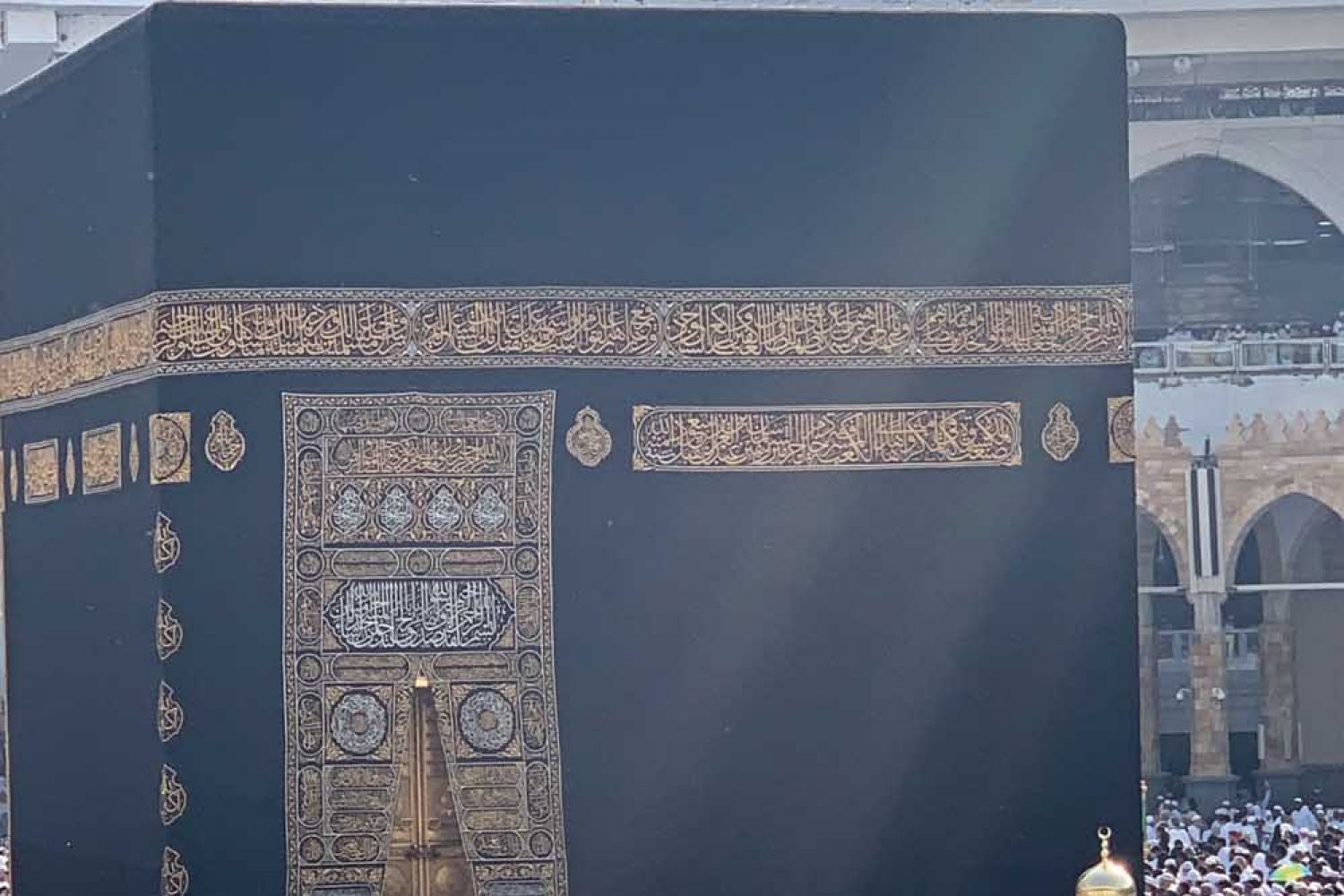

It was the first Friday in Ramadan and Umm Muhammad’s boss was assigning duties to the women at the Grand Mosque in Mecca. “Form a human chain if you need to but remember to control the women,” he said. The women set off for King Fahd Gate, a central gateway to the Ka’aba, the holiest site in Islam, a sanctuary for Muslims worldwide.The women in their long black robes walked across the white marble, faces shielded from the harsh sun by a niqab, hands and feet covered in black. Their sile