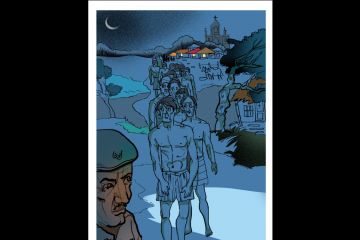

Being observed,

When observation is not sympathy,

Is just being tortured.

—Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh, 1857.

In her lifetime, Elizabeth Browning was hailed as Britain’s greatest ever woman poet and Aurora Leigh was considered first significant literature on female independence.

According to Virginia Woolf: “Rather it (Aurora Leigh) is a masterpiece in embryo: a work whose genius floats diffused and fluctuating in some prenatal stage waiting the final stroke of creative power to bring it into being. Stimulating and boring, ungainly and beautiful, monstrous and brilliant all by turns, it still nevertheless rouses our interest and respect.”

As Elizabeth Browning says, when observation is not sympathy, being watched is just being tortured. And, most of time, we’re being watched and we’re being tortured with the help of technology.

Our devices and technologies that run them extract our personal data in multiple ways and formats. Governments do it. Non-profits do it. Small businesses do it. Giant corporations do it. Schools do it. Colleges do it. They not only harvest it but analyse it, mine it for clues into our interests and likes and dislikes. In many cases, they sell the data to third parties. In the end, they have a digital avatar based on the data—the dioramas of your own self you fall in love with.

In addition to extracting personal data, population-level, societal-level data collection is the norm. It may be necessary for administering the country but without strong legal back-up, the data can be used for nefarious purposes. Fountain Ink magazine featured the way Aadhaar's various contractors were closely connected with America’s Central Intelligence Agency and other defence departments. Many city administrations such as Chennai, Hyderabad, Delhi use facial recognition technology to extract images from CCTV cameras and match them with the Crime and Criminal Tracking Networks and System (CCTNS) database. The technology can track who you are, where you are, what you do, and who you are with.

The CCTNS is a central government scheme being implemented in partnership with states country-wide on “mission mode” to connect more than 14,000 police stations to a central database under the National Crime Records Bureau.

According to Amnesty International, Hyderabad, is one of the most surveilled cities in the world. Airports in India are using Digi Yatra that uses facial recognition technology to verify passenger identities, a data collection exercise that is palmed off to a private player without any clarity on norms for privacy, storage and its subsequent monetisation.

As per Panoptic Tracker, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) again issued bids for the creation of a National Facial Recognition System (AFRS). It’s purported goal is to create a national database of photographs and quickly identify criminals by gathering existing data from other databases.

According to Panoptic Tracker, “use of this technology without having legal safeguards in place could lead to harms such as discrimination and exclusion which will be difficult to undo. Additionally, in the absence of a strong data protection law, use of this technology could lead to mass surveillance.”

Project Panotpic is run by the Internet Freedom Foundation, an Indian digital liberties organsation that seeks to bring transparency and accountability among government stakeholders in the deployment and implementation of Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) in India.

All of this ‘being observed’, in the words of Browning, at the personal and societal level, is not sympathy.

Anurag Mehra, a professor at the Center for Policy Studies at IIT Bombay says India needs more field work to know how the collected data is being used. He emphasises tracking field reports of Aadhaar failure or the encouragement of DigiYatra, and the linking of all other IDs to Aadhaar.

In the case of failure of Aadhar authentication, non-delivery of benefits results in a harm that is immediate and apparent. In other cases like DigiYatra, we do not know how it is being used or sold or what are the security hazards, he says.

About where this data harvesting and mining will end up, Mehra says, “I don’t know if this will result in more suppression or arrests, but surveillance is increasing, with more and more cameras and services that require use of biometric data—Aadhaar authentication or facial recognition.”

Our online activity—the scrolling, the clicking, the sharing—creates a continuously evolving digital avatar of each one of us. Algorithms analyse these cottony selves and get back to us at the personal level.

We’re uploading ourselves into the Web relentlessly. We people the Web with our avatars. Profiles of our age, job, address, location, what we read and who we are friends with, our politics, friends, hobbies, travels, social media exist in databases. Your Google search bar finishes your search query; you get the type of news you likely read previously. All this data is matched up with credit cards, and personalised and customised ads motivate and trigger your instincts for purchasing products.

All of this comes down to having a love for our nice, smart, beautiful avatars of ourselves. That is not a problem, and that is not far outside the edge because we’re always creating a “self”, all the time, even in a dream where you’re a knight in shining armour, a Ponniyan Selvan, may be Part I, if not the whole. In Indian philosophy, it is encapsulated in the term “jiva shristi”.

There are, of course, some bad people in avatars of our own self, some good ones, and an awful lot in between, sliding up and down the slope of ethics, morality, convenience, practicality and whatever is handy at the moment. Moreover, as Freud and Jung have shown, these avatars never really vanish; they drop down into the unconscious, and lie brooding, suppressed and repressed. A similar thing happens with online activity; all the digital selves we create are in the gargantuan servers and cloud.

Our online activity—the scrolling, the clicking, the sharing—creates a continuously evolving digital avatar of each one of us. Algorithms analyse these cottony selves and get back to us at the personal level.

Both at individual and mass levels, surveillance has been normalised with all the technologies and platforms that are in use. Surveillance refers to tracking who you are, what you do, where you go and what you buy. In an article in Slate magazine, public-interest technologist and security expert Bruce Schneier distinguishes between surveillance and spying:

“Spying and surveillance are different but related things. If I hired a private detective to spy on you, that detective could hide a bug in your home or car, tap your phone, and listen to what you said. At the end, I would get a report of all the conversations you had and the contents of those conversations. If I hired that same private detective to put you under surveillance, I would get a different report: where you went, whom you talked to, what you purchased, what you did.”

While the internet enabled mass surveillance, Schneier warns, artificial intelligence tools enable mass spying. Spying is about intent, about summarising the content of, say, your conversation with others. Humans were required to make sense of that. Now, generative AI tools summarise well and can replace humans doing the same job and potentially increasing mass spying by orders of magnitude.

How have internet technologies enabled mass surveillance and in what dirction have data extraction, harvesting and mining led the world? Harvard business school professor emerita and tech activist Shoshana Zuboff in her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, traces the trajectory of capitalism that was oriented towards mass production and consumption in the industrial society to individual-oriented consumption in digital times. Technology enabled supply and demand to match up at the individual level.

Individual needs, technology know-how and means, alignment of supply and demand, the economic and financial profits of technology companies and monetisation—all of it coalesced in the digital milieu. Zuboff says it undermines personal autonomy and democracy.

She calls it “surveillance capitalism,” which takes private human experience as a source of free raw material, brings it under market dynamics, packages it as behavioural data, which are then analysed using computation tools to produce predictions of human behaviour. These predictions are then sold to businesses and markets who are interested in what people will buy, eat and do stuff. The key idea she discusses is “behavioural surplus.”

For instance, Google, in the early 2000s, knew it had that “surplus.” Not only did it have IP addresses, search histories, it also had metadata of what a person or user in the search bar is, a digital “you” that can be addressed with customised ads. Creation of consumer profiles was a surplus that can be monetised and Google did exactly that.

The greatest success of data harvesting and mining companies and governments is making people believe that what they are doing is good for people, is friendly, necessary and largely fun for the populace.

Even when people realise the dangers of dishing out data, there are number of reasons that make people give in. Mehra reckons it has to do with convenience, fatigue about trying to control and then feeling tired, or coercion, that is, a service will not work unless you give data. Promises of better delivery of service, economic incentives, better futures—anything is grist to the mill for the data harvester.

Data extraction and packaging it for prediction markets started with online targeted advertising. Zuboff says it doesn’t stay put in the same place. She charts out how all of this is moving, in what direction and to what effect, in an interview for NY Mag.

When there was a slump in the sales of Ford vehicles, their CEO zeroed in on the value of data and its collection as a way out of their market blues.

“How do we do that? We’re going to become a data company. We got 100 million people driving around in Ford vehicles. And what we’re gonna do is, we’re gonna now figure out how to get all the data out of this driving experience,” Zuboff puts the words to the thinking that went on within Ford.

Combing telecommunications and informatics—telematics—motor companies now know everything about the driver. They, as Zuboff says, are like “ we know the gaze of your eyes—and that’s really important for insurers, to know if you’re driving safely. And we can know what you’re talking about in your car, and, like, Amazon and Google and so forth, are already in a contest for the car dashboard, because that’s a way of hearing what you’re talking about and knowing where you’re going.”

Zuboff says now the automobile itself becomes this little surveillance bubble. All the information collected in that bubble, your conversations, the flap of your eyelids, your driver inputs, all of that has “predictive value for all kinds of business customers”.

For Zuboff, surveillance capitalism sprang from the behaviourist school of psychology. The chief proponents of behaviourism were John Watson, Walter Hunter and B. F. Skinner. They didn’t admit the existence of mind. Consciousness, for them, was stimulus-response (S-R) phenomenon of nerves.

Zuboff thinks technologies like biometric identification closely hue to surveillance capitalism’s dalliance with behaviourism. She says this phenomenon is a new variant of capitalism and her book focuses on companies doing it.

Zuboff thinks technologies like biometric identification closely mirror surveillance capitalism’s dalliance with behaviorism. She says this phenomenon is a new variant of capitalism and her book focuses on companies doing it.

Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias in their book, The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism, draw similarities between historical colonialism and data colonialism. Just as historical colonialism appropriated land, nature, and human bodies for profit, data colonialism is “the appropriation of human life so that data can be continuously extracted from it for profit.” The authors point out that data colonialism is a continuation of the capitalist practice of extracting maximum value and hoarding wealth and power in a small cabal.

Colin Koopman’s work shows how pervasive the problem is and how vulnerable we are “in the sense of being exposed to big, impersonal systems or systemic fluctuations.” He is the chairman of the philosophy department at the University of Oregon and the author of How We Became Our Data: A Genealogy of the Informational Person

In an interview to New York Times magazine, he says, “Your data has become something that is increasingly inescapable.

“There’s so much of our lives that are woven through or made possible by various data points that we accumulate around ourselves—and that’s interesting and concerning. It now becomes possible to say: ‘These data points are essential to who I am. I need to tend to them, and I feel overwhelmed by them. I feel like it’s being manipulated beyond my control.’ A lot of people have that relationship to their credit score, for example. It’s both very important to them and very mysterious.”

The underlying theme of analysing and understanding what has been wrought in data extraction is that it is hacking away at personal autonomy.

As Mehra, the IIT Bombay professor, says, the problem is acute because of issues like who has access to personal data, how it is used, and what they are doing with it.

The greatest success of data harvesting and mining companies and governments is making people believe that what they are doing is good for people, is friendly, necessary and largely fun for the populace.

Professor of history and philosophy of science at the Université Paris Diderot, Justin H Smith, sticks it closer in an essay in Unherd on how tech is claiming our bodies:

“It is not hard to imagine a near-future scenario in which countless data-points from all of our bodies are quietly and unceasingly transmitted to the cloud and available for inspection by “the authorities”: how many calories we consume per day, how often we get sexually aroused, as well as the old standards of steps, heart-rate, blood-sugar, and so on.”

You might take the technology and devices that measure your calories, monitor your sugar levels as necessary. At some point, it becomes a data harvesting operation, a surplus Zuboff talks about, a torture, in the words of Browning, because it is not sympathy. It is then packaged and sold to businesses or used by the state agencies for their own ends. Surveillance, according to Bruce Schneier, has become the business model of the Internet.

If technology so far can create the surveillance that can feel like a safety cocoon, it’s anybody’s guess what artificial intelligence—at the moment an algorithm that parses large data—can and will do. Israel reportedly used AI to prepare its kill list and bomb people in Gaza.

As far as India is concerned, it is nowhere at the moment compared to the West in deploying these technologies. The government allotted ₹5,000 crore for purchasing computing power. A part of the ₹10,000-crore India AI mission, this fund is for acquiring more than 10,000 Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), and run models. Recently, the government launched a Multimodal Large Language Model initiative to improve public delivery and citizen engagement. Local language models such as Sarvam, Chitralekha and others entered the scene.

Whatever the ramifications of the latest tech, Mehra says, “The technology is upon us and people will use [it], you can’t do much [abou it]. If you use AI/LLMs you will get the same benefits of automation as anyone is getting.” He thinks AI deployment is quite substantial in Indian IT companies and “that is why their hiring is declining”.

Joseph Mathai, a Delhi based human rights activist, says digital tools definitely streamline personal and professional interactions, saving time and resources.

“Digitization also raises critical ethical, psychological, and societal questions,” he says. “Balancing technological convenience with the preservation of authentic human connections requires thoughtful integration of digital tools, prioritising empathy, inclusivity, and individual well-being.”

According to Mathai, the balance, “lies in ethical data collection, ensuring transparency, consent, and accountability. Technologies like encryption, anonymisation, and legal frameworks can help safeguard individual rights while leveraging information for societal benefits.”

With the safety and reliability of large language models, trained on large datasets, coming into focus, it’s difficult to fathom what’s in store for people and societies. Large machine learning systems are trawling the data, both real-time and accumulated. It is beyond anyone’s grasp as to what they will see and say, things we would never have seen and said, about us, about our friends and neighbours, about our communities and societies. Every data merchant worth his coordinates is going to get gob smacked and a while later, going to smack his lips at the things revealed. As Schneier warns artificial intelligence enables spying, at a level that is unprecedented.

For pulling back things a bit back to sanity, Mehra says, “We need privacy laws, security related regulations, serious data handling protocols.”

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a great law that lays out principles to processing personal data. They include lawfulness, fairness, and transparency; purpose limitation, data minimisation, accuracy, storage limitation, integrity and confidentiality; and accountability.

Data breaches, intentional or negligent, failure to keep records of personal data collection and processing, not complying with orders—all invite heavy penalties, as per GDPR. A similar law is urgently needed for India.

With all the tools available, both for broadcasting our thoughts, feeling, visits, locations, likes and dislikes, text, audio, video, and also summarising them with AI tools, we are in the digital equivalent of the Cambrian era where our fleeting dioramas take on life, and walk into the digital netherworld where companies and governments lie in wait and watch, and seek profit from this richness. Physicality, utter physicality, has never been at a greater discount, never been more precious than now.