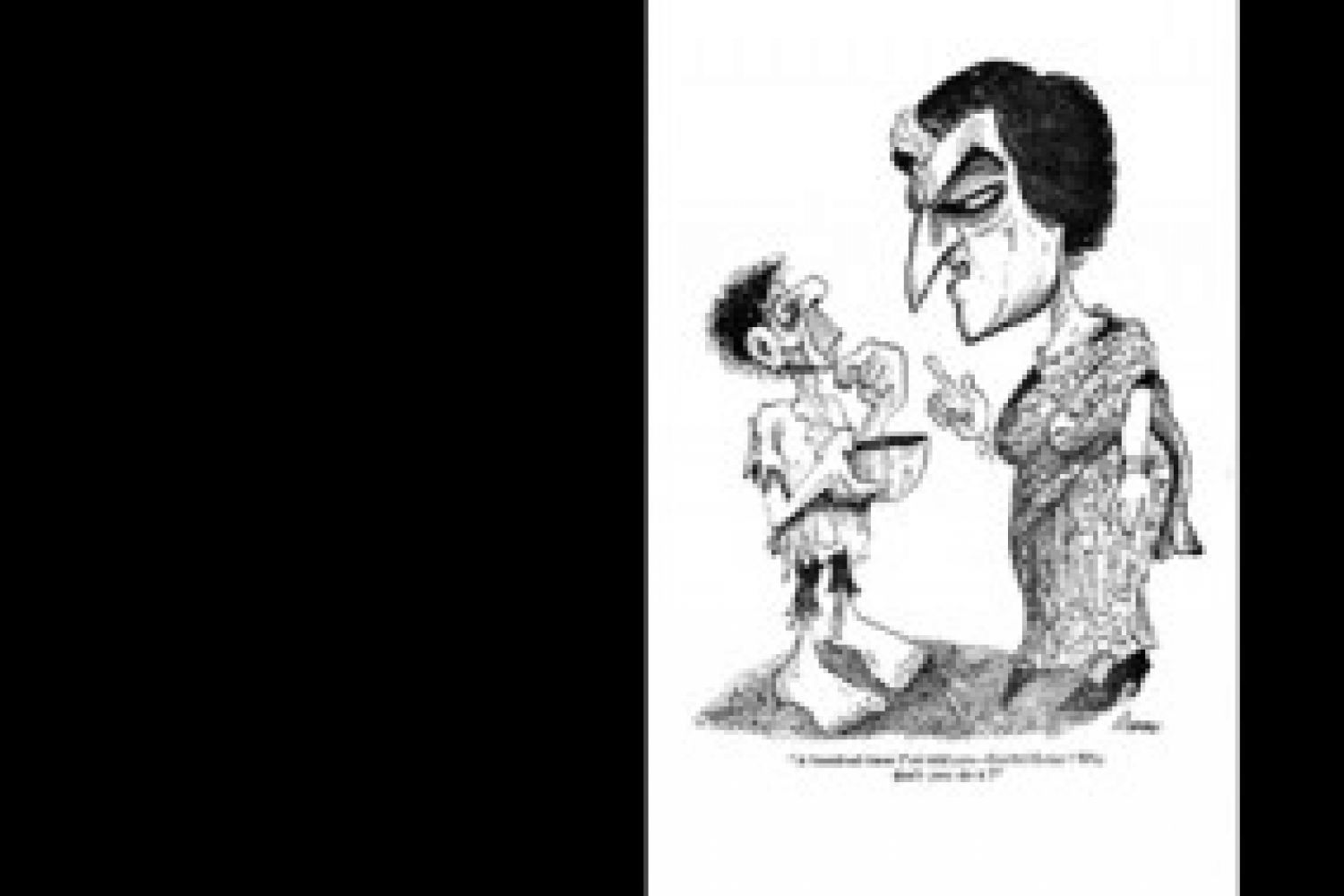

Rajinder Puri (September 20, 1934–February 16, 2015) was an

exceptional cartoonist and political columnist. His work in both areas was

marked by a directness and purity of purpose seldom, if ever, seen in the

oeuvre of any Indian cartoonist or columnist. He had a marked gift for incisive

drawing and writing. There were others like O. V. Vijayan, who could draw and

write expressively, but none had Puri’s bent for savage satire which, no doubt,

had a connection with the Partition, an even