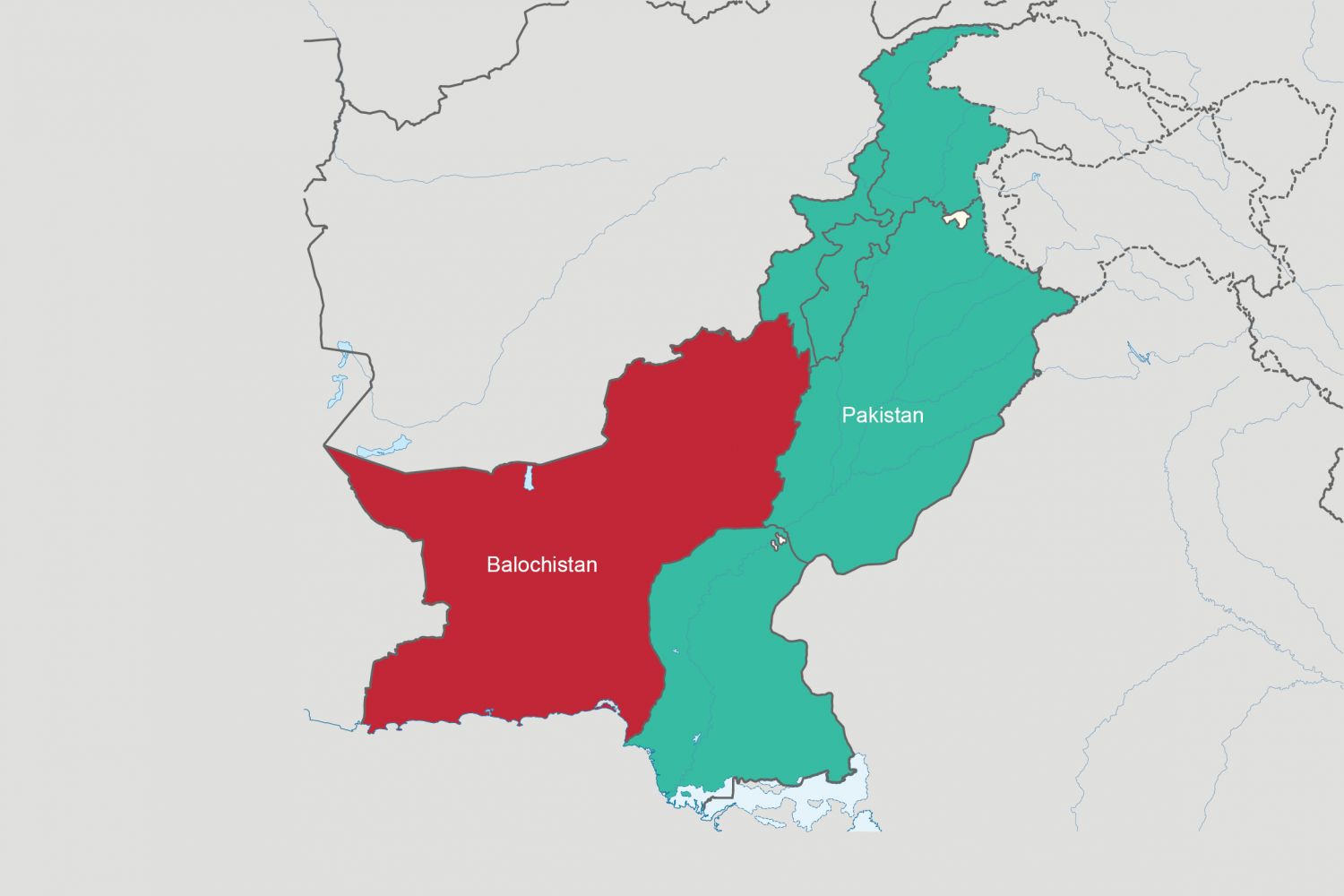

Pakistan, from inception, is a country wracked by violent

dissent often bordering on civil war. It lost half its territory after the

secession of East Pakistan (Bangladesh) but the problem doesn’t go away. Indeed

the oldest resistance to Islamabad is not Bengali but Baloch in origin. There

have been five major conflicts in Balochistan province, starting from the Raj

days. The fifth and latest has continued for more than a decade, from 2004 to

the present day. The reasons are a complex and