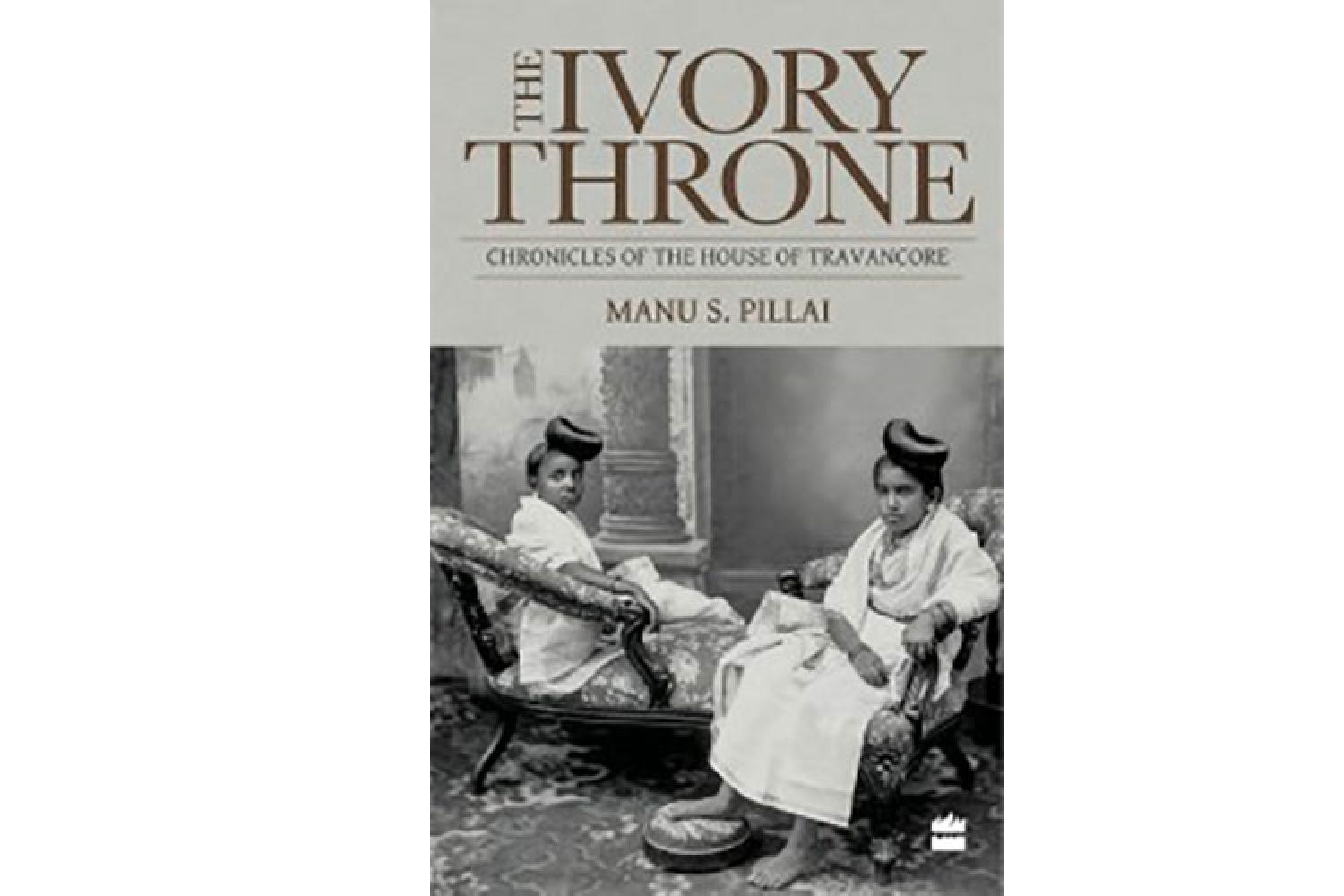

In The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore,

(Harper Collins India, 2015) Manu S. Pillai tries to write accessible history

as well reclaim the reputation of one of British India’s most remarkable

rulers, Maharani Sethu Lakshmi Bayi who ruled the erstwhile princely state of

Travancore as regent. There is always a narrative tension between these

differing tasks of the historian, but Pillai manages it quite well, easily

switching back and forth between historical narrative and