India trumpets the

tablet computer Aakash as low-cost, high-tech innovation required to bridge the

digital divide. It couldn’t be more wrong.

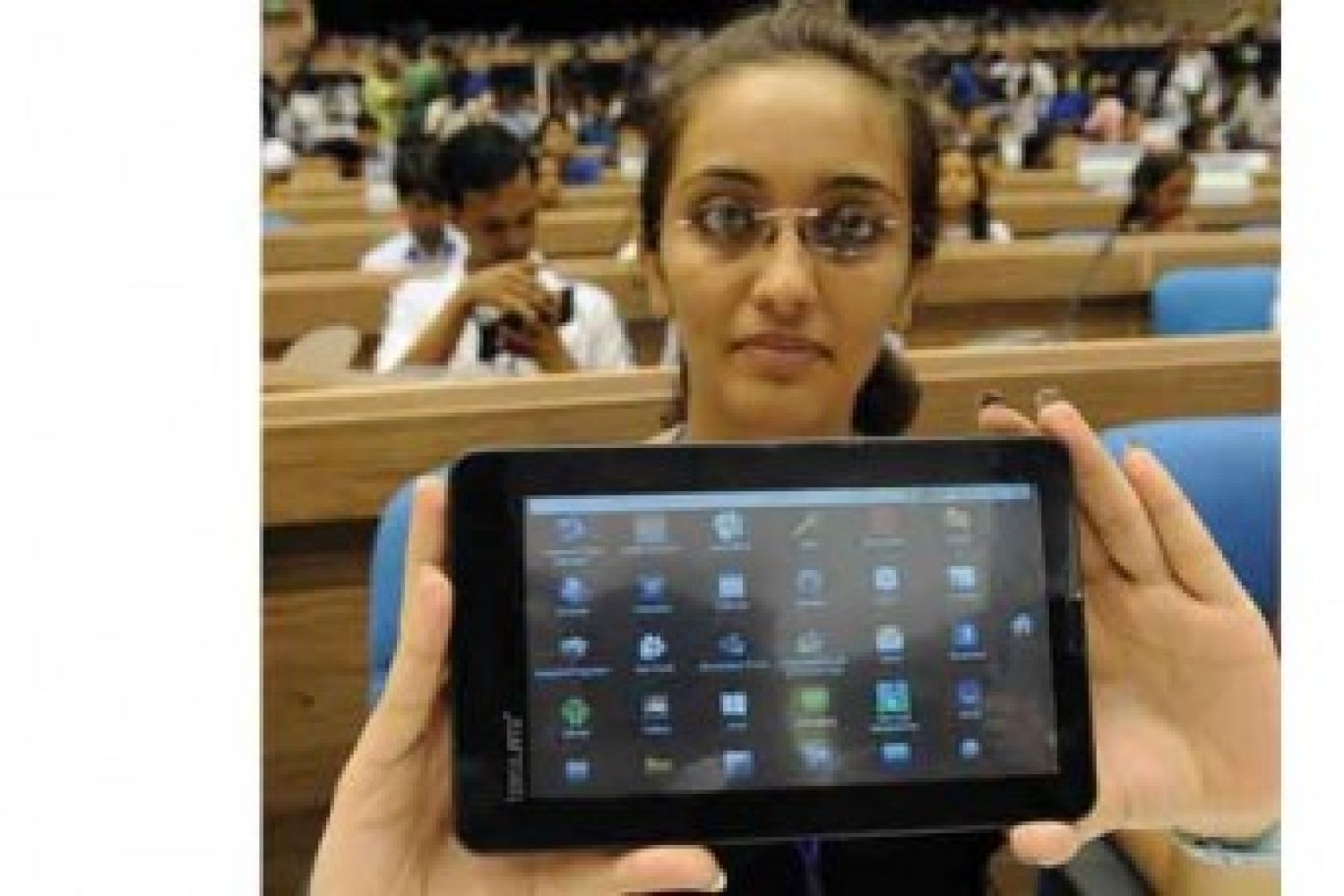

Aakash is not true

innovation. It is a simple contract manufacturing job that should make scrappy

computer makers swell with pride, not something that behooves an IT behemoth

and a nation on the rise. It would have been a remarkable story if the nation had

actually created such a low-cost computer. But it has merely assembled one

through a third