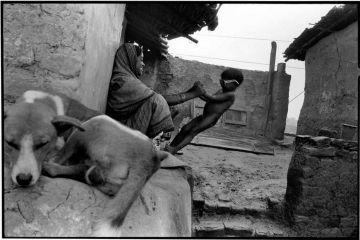

From age five Amandeep

Singh Nihang was raised as a crusader. Though, now at 25, he doesn’t know for

whom or for what he has to fight. The youngest of the five sons born to a poor

peasant in a village near Faridkot, Amandeep gave no choice to his parents but

to send him to the “dera” of Baba Gurcharan Singh, to make him a Nihang. Under

the Guru’s care Amandeep took up riding, cooking, washing, firing heavier and

lighter guns with a sniper’s precision, mastering swords and other

f