In June 2017 violent

farmer protests broke out in Madhya Pradesh catching the BJP government of

Shivraj Singh Chouhan by surprise. In the police firing that followed five

farmers were killed in Mandsaur district, catapulting what would have been an

easily ignored regional protest to national news. In the coverage that

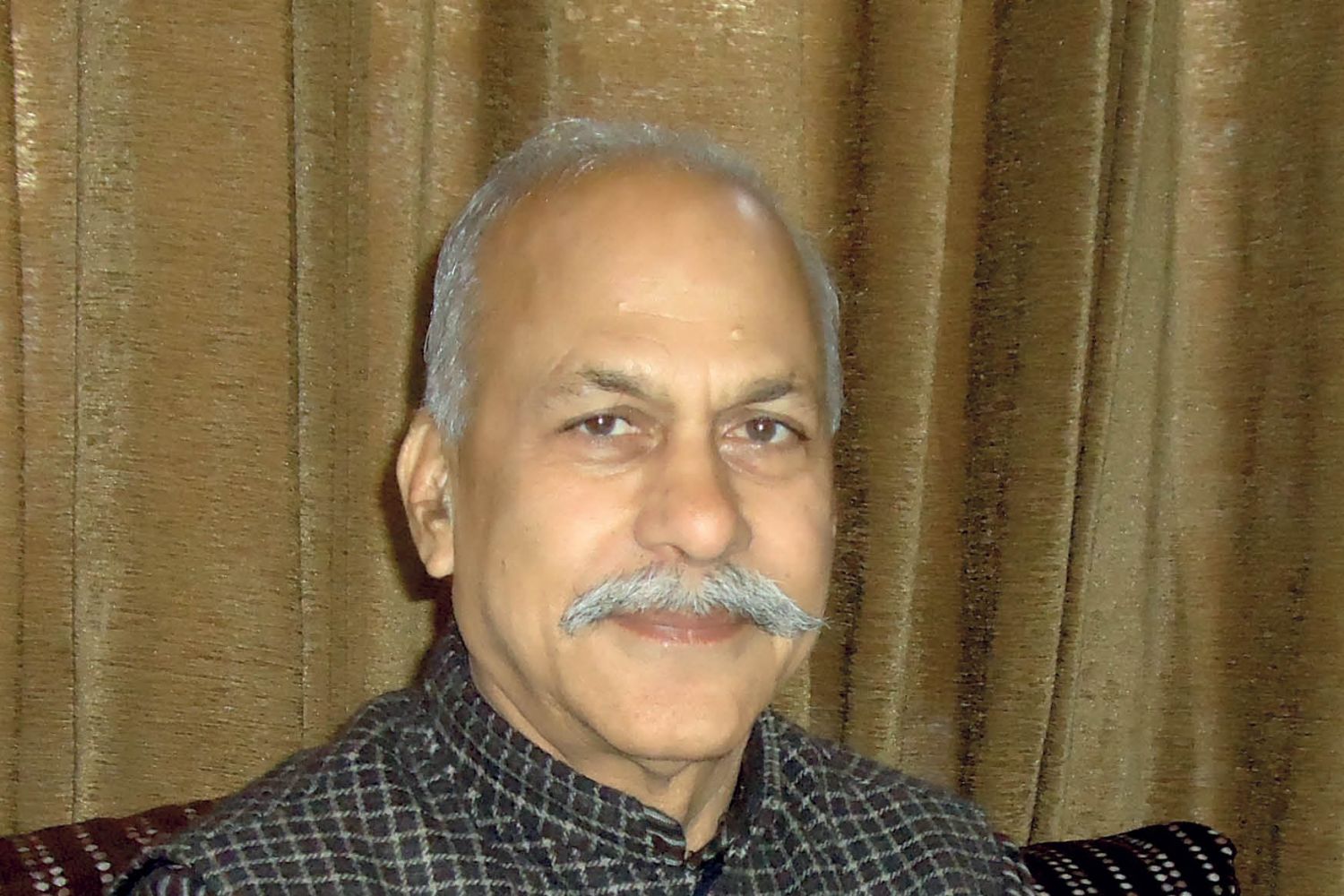

followed one name kept cropping up—Shiv Kumar Sharma or Kakkaji as he’s known

to his supporters. In the fragmented and disorganised state of Indian farmer’s

movements a

Continue reading “'The farmer is learning to fight for his rights'”

Read this story with a subscription.