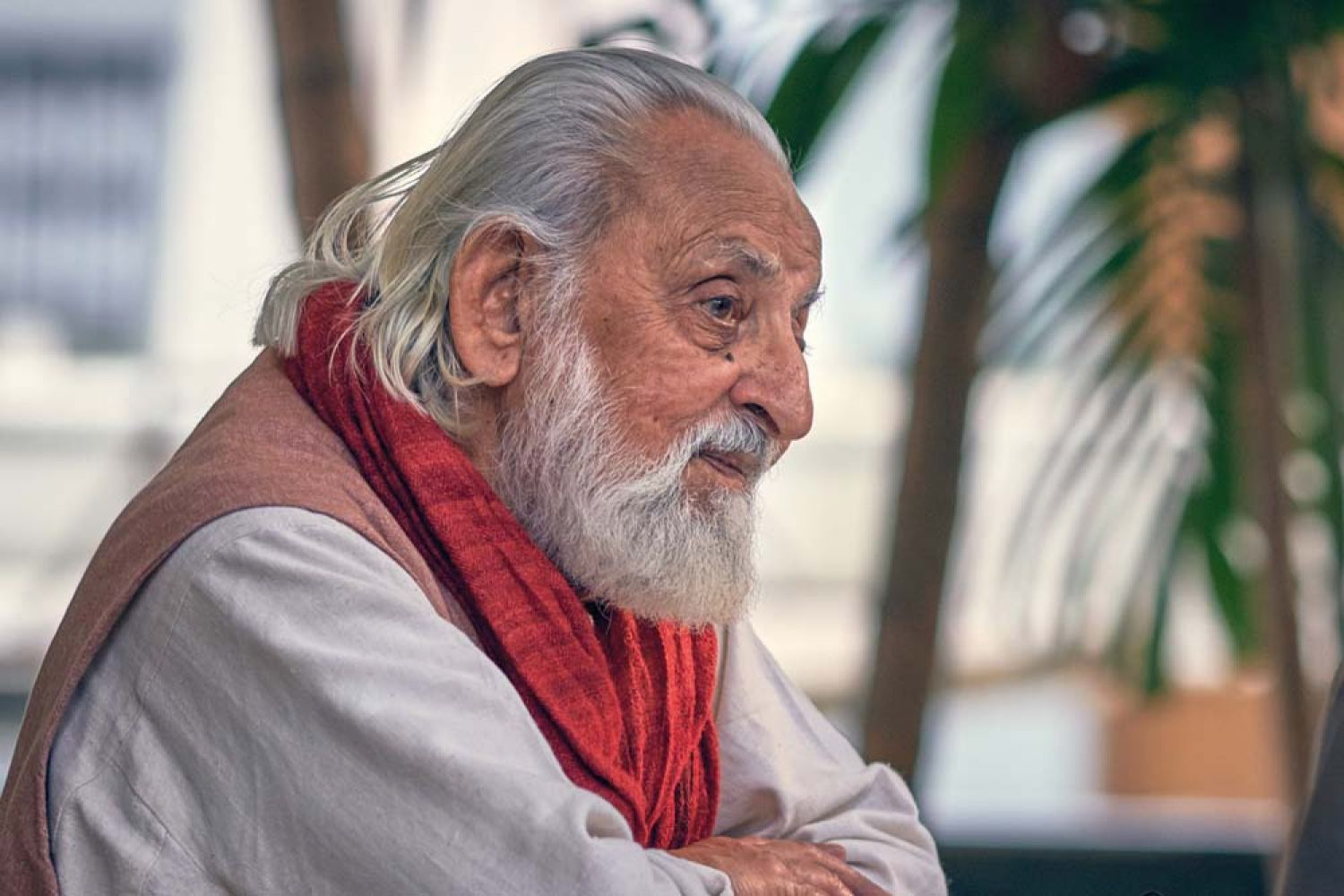

M.S. Sathyu is upset. On the first of a five-day screening of his works at the

National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) in Bengaluru, the 88-year-old director is

aghast at the 20 rupees entry fee. He energetically marches up to the

director’s office, and reports back that the officer, a recent appointment,

won’t budge. He apologises to the audience.

Protest against authority has been central to his career. In

2004, Sathyu successfully fought a case in the Supreme Court after the West

Be

Continue reading “'There's nothing called freedom of expression'”

Read this story with a subscription.