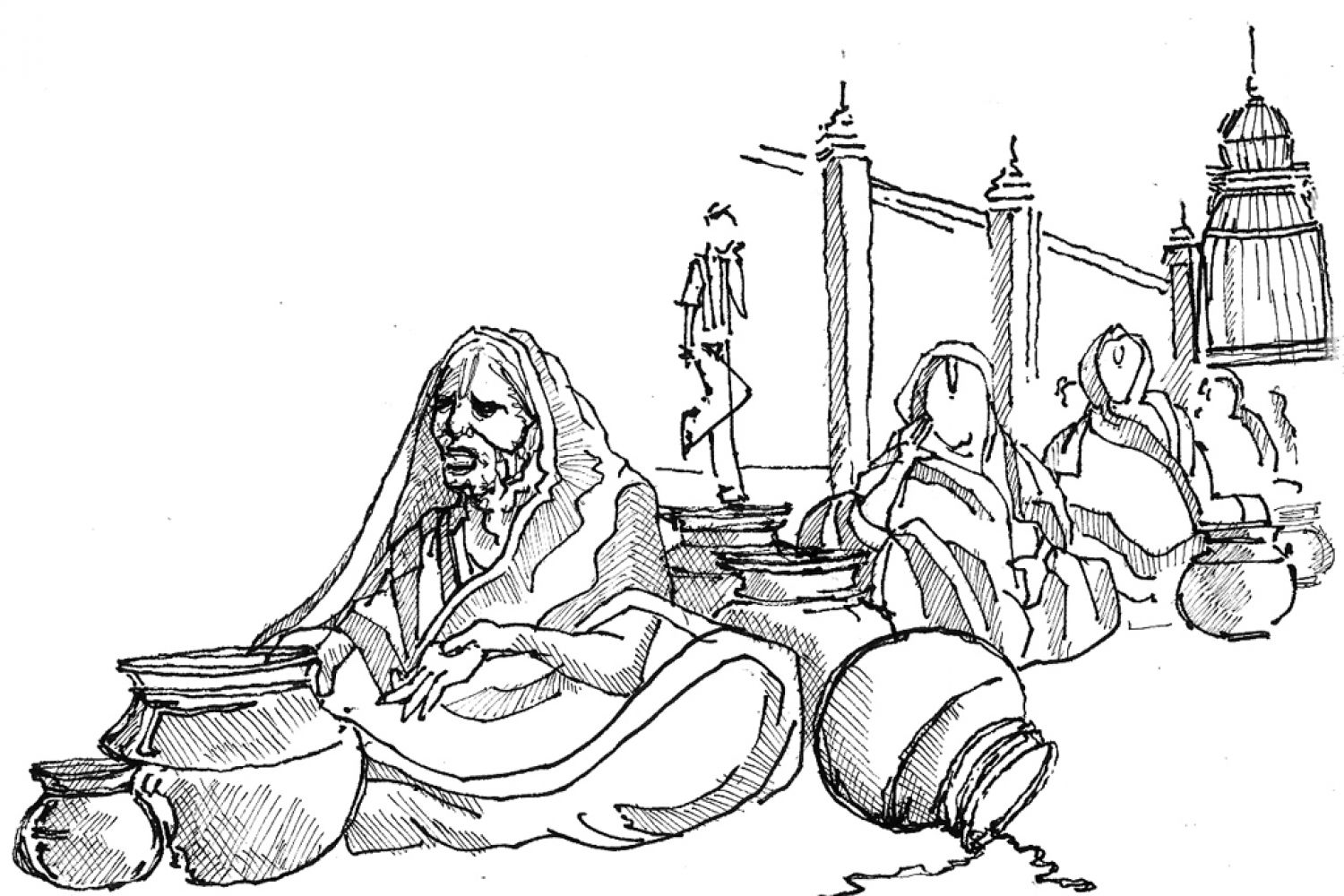

The puddle on that

January morning was cold. The skin on her leg was torn and blood oozed slowly.

Her wrinkled, baton-shaped arms failed her when she tried to get up. She called

for help. There were 50 widows within 50 metres: all busy, caught in a frenzy

to fill water from a borewell in worn-out disposable bottles abusing, pushing,

falling, and kicking each other. Five years ago, 65-year-old Chandralekha came

to Mahila Ashray Sadan in Chaitanya Vihar, Vrindavan, a house for destitute, wido

Continue reading “Gateway to heaven is hell on earth”

Read this story with a subscription.